How We Talk About Media Refusal, Part 1: “Addiction”

Laura Portwood-Stacer / New York University

This is the first of a series of three posts I’ll be doing in Flow about the topic of “media refusal,” which I define as the active and conscious rejection of a media technology or platform by its potential users. In these posts, I’ll be discussing how popular discourse tends to frame practices of media refusal and what implications these frames might have for the way we understand our participation in media culture. In particular, I’ll be focusing on discourse around the refusal of social media platforms (such as Facebook).

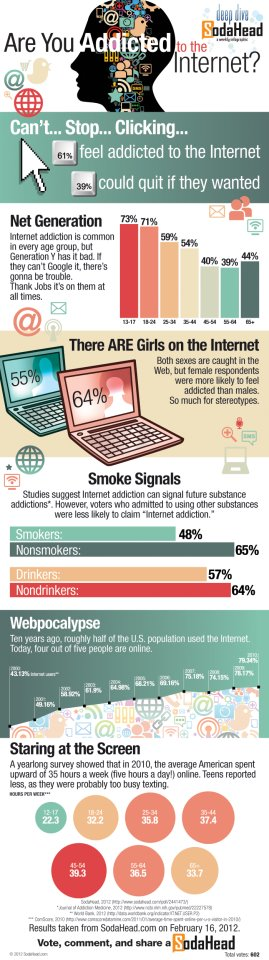

When people talk about why social media technologies are troublesome, and thus why they may need to be refused in our lives, they often invoke the concept of “addiction.” People who have deactivated their Facebook accounts sometimes describe it as “quitting cold turkey” or recount experiencing symptoms of “withdrawal.” In 2011, tech festival South by Southwest Interactive offered a presentation on “How to Liberate Yourself From Digital Addiction” and just this summer, social media news blog Mashable posted an article on “6 Ways to Kick Your Facebook Addiction.” The 71 million hits returned when Googling “Facebook addiction” suggest that there is something of a moral panic going around about people’s practices of Facebook use. What is clear is that addiction has become a commonsense frame through which media producers, and media consumers themselves, represent problematic levels of consumption. But what are the implications of this diagnosis? What treatment might be suggested for this epidemic? As with other forms of addiction, the ultimate solution implied is for individuals to take the responsibility to stop using the problematic substance.

While the addiction frame might paint media technologies as dangerous substances that should be used in moderation if used at all, it can also establish a pathological other—the addict—who, through comparison, makes the rest of us more comfortable with our own levels of consumption. Addiction is what takes a “natural” human activity and makes it culturally unacceptable (think of “sex addiction” for example). In this way the addiction metaphor might actually work to naturalize “normal” degrees of use among most of the population. Consumer culture and the corporations which power it are thus left unproblematized, while individual pathological behaviors are subjected to scrutiny and critique.

Practices of media refusal, as well as statements by media refusers about their choices, could be seen as implicit indictments of the norms of media culture, the most basic norm being that everyone ought to be a consumer of media. Yet media refusal is usually understood and practiced individually (though there have been a few campaigns aimed at getting people to collectively) unplug. This individual response to a collective problem is typical of contemporary “lifestyle politics” in which resistance tactics are arguably more effective at generating further consumption (of self-help magazines, for example) than actually altering objectionable aspects of consumer culture.

Discourse that positions media consumption as an addiction is not new. For example, Jason Mittell showed over a decade ago that critics of television have long used the language of addiction to condemn the presumed social effects of that medium. As Mittell pointed out in his analysis of discourses that position television as a “plug-in drug”, framing a media technology as an abusable substance has implications for the proposed solutions and the thinkable responses. If, for instance, we see social media technologies as deterministic relationship-ruiners, and we are encouraged to understand the tendency to succumb as indication of personal moral failure, then the solution is either individuals making the choice to opt out or regulation aimed at controlling the problem substance and saving people from themselves. Regulation is a tough sell in the contemporary political economic context—unless it involves the protection of corporate property—and so the result is a rehash of the neoliberal responsibilization we’ve seen in so many other areas of “ethical consumption” (such as the market for eco-friendly products).

While Mittell argued that understanding our culture’s consumption of television as being like a society-wide drug abuse epidemic implied the necessity of a certain kind of response – a policy-driven “War On Drugs”-style campaign to regulate television consumption down to culturally safe levels, I want to argue that, in the 2010s the addiction metaphor carries with it another set of solution implications. As Micki McGee has cogently argued, we live in an era in which self-help and lifestyle management are the dominant modes of problem solving advocated for an array of cultural scourges, usually with the help of expert coaches (or even medical professionals) who are paid for their services. They may be paid directly, but more often experts who promise to help people fight media addiction offer their advice in the form of commodified media content itself, such as web videos, blogs, books, and even social media accounts(!). Even journalists seem to position themselves as participants in this lifestyle project, with news outlets running story after story about how the rampant consumption of social media is affecting our lives and our society for the worse.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p-qOeluZN-I[/youtube]

Most recently, a new psychological study was released, in which researchers in Bergen, Norway claimed to have developed a valid scale for identifying Facebook addiction. Jenny Davis has pointed out how professional medical understandings of media addiction filter down to public and even academic discourse about media consumption, with implications for how we popularly understand our own media use as well as how we think we ought to respond when it becomes problematic. Popular discussions of Facebook addiction center around identifying who should be treated and teaching consumers how to treat themselves once they’ve recognized the signs of trouble. The popular media coverage of the Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale bears out this point. For example, a Jezebel post offers the Bergen Scale as a “quiz” its readers can take for themselves, and then (facetiously?) encourages readers to post their scores as status updates.

As audiences, we are constantly told that the addiction some of us have to social media is a problem, and the solution offered is to monitor ourselves and our friends, to be on the lookout for signs of this pathology, and to keep coming back to the experts for advice and reassurance that we are handling ourselves properly. In the process, even if we attempt to refuse media consumption on one platform, we simultaneously reinstantiate ourselves as media consumers in others! Addicted to social media? Read this blog to find out! Have a problem? Buy this book to cure it! Quit Facebook, then tune in to our Action News Special Report! We are thus never beyond the reach of advertisers and the other ideologues of consumer culture as a whole. The dynamics we may have wished to escape do not disappear from our lives so much as they appear in different form. This suggests that framing social media platforms as addictive substances that can be rejected “cold turkey” is not a very effective way of naming and treating a social problem so much as it is a driver for further media consumption.

In my next post, I will talk in more depth about how self-surveillance and self-control—as expressed through media refusal—are offered as individualized strategies that promise to cure the cultural ailment of media addiction, while simultaneously crafting selves who possess moral integrity, among other desirable qualities.

Image Credits:

1. The face of addiction

2. Can’t…stop…clicking…

3. Screen Free Week

4. Lost in a flickering haze

Please feel free to comment.

A well thought out article by Laura Portwood which indicates how the crucial issues about the politics of social media can be obscured in pseudo scientific discourse which with the metaphor of addiction sanitizes the whole problem of uses and gratifications of the facebook. There is no doubt that as Stanley Cubrick has shown in Clockwork orange modern societies can use any form of culture, high or low to condition its subjects.Similarly the facebook following the older media can be commodified and instead of being used as social forum become big emporium populated by consumer goods, and the facebook instead of acting as a public sphere become a prison house of illusions.( Wim Wenders has also dealt with the hypnotizing capacities of the proliferation of images in his film till the end of the world. On the other hand as the Arab revolution and the movements of the indignados has shown the facebook can be used as a medium of emancipation and social awakening .So media refusal is a double edged sword as was cogently argued it can sensitize to the dangers of over

exposure but can obliterate the discourse about the capacity of the facebook to act as a new public sphere.

Interesting article, Laura. I look forward to your others.

When I first saw “Media Refusal” in your title, I was expecting you to be writing about mostly about those who really refuse to engage with various media technologies or commercial/mainstream media culture at large, rather than those who disengage with them after some time of engagement.

It’s long surprised me how little attention has been given to individuals and groups who refuse to engage with mainstream media culture, which I think comes from a false assumption that everyone does. The spectrum of media consumption among most media scholars therefore seems to run from distracted engagement to fandom, without consideration of non-engagement. This seems largely class-based, I think, with many middle-class folks assuming that their relationships with media are universal. This notion of ubiquitous mainstream media consumption seems to be even more prevalent now than it was 15 years ago before the Internet and our various technologies for accessing it became so prevalent.

While there are numerous reasons folks don’t engage with mainstream media, non-engagement has also been framed recently via the discourse of “access.” As talk about the “digital divide” has largely died down, more attention should be given to the amount of time individuals have to invest in social networking sites, for example. In addition, I’d really love to see more media scholars interested in consumption talking to folks who really refuse to consume media, for this would help us to understand better not only the much wider spectrum of media consumption, but also the various practices of opposition.

Maria,

Thank you for your comment! I absolutely agree with you that media platforms, as well as users’ responses to them, are often “double edged.” Just as Facebook is more complicated than the accounts that would characterize it as simply a completely commodified marketplace or a progressive (even revolutionary) social technology, the practice of refusal is also double edged. There’s a lot more to it than meets the eye at first, which is hopefully what I’ve started to get across here. Thanks for reading!

Mary,

Thank you for your comment – I really appreciate your interest. I definitely agree that by paying attention to practices of refusal we can learn something valuable about media consumption more generally, including the taken-for-granted norms of media scholars and even mainstream consumers. There are some great projects in the works right now where scholars have been talking to refusers – I organized an SCMS panel this past year with really interesting presentations by Rivka Ribak and Michele Rosenthal, as well as Louise Woodstock, who are all conducting empirical research with media and technology refusers. Jessica Roberts and Jenny Davis (two of my co-panelists at the Theorizing the Web conference this past spring) are thinking through these issues too. I’m sure there are more of us out there – hopefully some of them will see this post and chime in as well!

I’m so glad you brought up the notion of access too. I think we have to stop assuming that those who are across the “digital divide” are just clamoring to become bigger media consumers, if only they were given the opportunity. Surely many people would take advantage of those opportunities were they more available, but the case of media refusers shows that there are legitimate critiques to be made of media culture, and we may obscure some of these when we reinforce the normativity of media consumption in our scholarship.

I’m still thinking through a lot of this, so I’m looking forward to having more conversations like this! Thanks for reading!

Thanks for your reply, Laura. So glad to hear about all this exciting work on media refusers. I look forward to your next column!

Pingback: How We Talk About Media Refusal, Part 2: Asceticism Laura Portwood-Stacer / New York University | Flow

Thanks for the very timely and needed article. I am a strong Facebook refusenick because it assumes we are or need to communication our feelings to many, and continuously. And now other programs and online news wants me to use it too. A T.V. program in Chicago had a contest, prize a trip to Las Vegas, in which we needed to “like” the program on Facebook.

Thanks.

Gene Loeb, Ph.D.

Pingback: How We Talk About Media Refusal, Part 3: Aesthetics Laura Portwood-Stacer / New York University | Flow

Interesting article and series, Laura. (Found through Twitter, and through the post on the Cyborgology site.) Lots of links to follow and directions to learn more. I’ve been trying to navigate myself through all the different modes of communication available these days. I’ve tried many of the social networking sites. I was a long time Facebook user, though I didn’t feel until the last few years that it was potentially problematic. I always had mixed feelings and experiences, but I recently decided the benefits weren’t worth the costs for me, and I stopped using it.

The addiction frame partially rings true for me. (I have been known to Google “internet addiction” or “Facebook addiction”, though generally what I find as top search results are not very helpful or intelligent.)

For Facebook, I really do feel that the addiction metaphor has some truth to it. I got the feeling that Facebook was intentionally doing things to keep me interested in the site, despite the fact that my interest was lagging. One way in which they do this is that they change the site frequently enough that one rarely has the time to really understand the dynamics under which one is operating. When I post a status update or a photo, then, there is always the feeling that this may reach someone that it normally wouldn’t. Instead of directed communication, one has partially directed communication, with a bit of gambling built in there. Maybe it will be highlighted on someone’s newsfeed, or maybe it won’t. My feeling was that somehow, something like 70% of the site and the rules under which is operates are well known and useful and controllable, but there’s a small part that keeps changing (and maybe this stimulation is what keeps people’s interest). So, although as a fixed communication platform, I agree that its maybe not so sensible to talk about addiction, as a changing platform controlled by a company that wants be to stay engaged, I do think the addiction picture has some validity.

Also, you make the point that

“While the addiction frame might paint media technologies as dangerous substances that should be used in moderation if used at all, it can also establish a pathological other—the addict—who, through comparison, makes the rest of us more comfortable with our own levels of consumption. … Consumer culture and the corporations which power it are thus left unproblematized, while individual pathological behaviors are subjected to scrutiny and critique.”

By focusing on the “Facebook refusers”, don’t you also do the same thing? Studying Facebook refusers as anomolies whose motivations need to be understood, you also can act to normalize a certain level of Facebook use, and make questioning it seem fringe. (Or maybe it really is by this point… then I guess I just have to accept being on the fringe…)

Thanks for your comments, Boaz (both here and over at Cyborgology). I think you are absolutely right that my research on Facebook refusers might work to further solidify their status as fringe or abnormal. However, I do think that I am only following a discourse that I observed elsewhere and thought would be worth understanding. About a year or so ago I started noticing blog posts and journalistic pieces talking about the new “trend” of people quitting Facebook – what struck me about that was the assumption by these writers that Facebook use was so universal that quitting could become a hip new thing to do! So I think you’re right that that assumption needs to be questioned. It’s also worth noting that, in some (probably unconscious) way, people who are active in blogging and Internet journalism have an interest in perpetuating a culture in which user involvement on the Internet and social media is the norm – that’s their audience and it’s how they get their hits! This isn’t to propose a conspiracy theory, but just to say that the “hegemony” of social media is least likely to be questioned by those who swim in its waters as a matter of course.

One more point – media refusers often take pride in their difference from the mainstream (there’s some great research on TV refusers that talks about this). So to some extent the “fringe” status could be a badge of honor. I for one love the fringe, and studying the people on it. :)

Thanks Laura- I appreciate your points. It would be interesting to see to what extent Facebook use is important in which demographics/communities around the world. My own situation is not so typical, perhaps. I live in France, and have watched Facebook become heavily used within the expat community in my city during the last few years. Its use took on a particularl strain for me since I wanted to use it to keep in touch with friends and family in the US and elsewhere in Europe, but felt it had the tendency to undermine my attempts to be more connected to the city and culture I live in. Further, I am trying to learn French, and though there is some French Facebook activity, not enough to form a critical mass, and I would basically stay in an English language environment if I used Facebook a lot. I saw the way in which Facebook seemed to consolidate cultural groups, and discourage mixing. Certainly not across the board, but this was my general impression. I also saw that it encouraged a laziness with respect to social interaction, that didn’t seem to me to be leading to deeper friendships, particularly amongst a rather mobile, temporary foreigner population. Anyway, perhaps this is off-topic, but maybe gives some more background on my comments.

After reading this piece, I felt that I could relate to some of the issues because I am currently a college student in this generation dependent on social media. Nearly everyone I know has a Facebook or a Twitter, and most are constantly connected to it whether they are on their computer or accessing it from their smartphone. In regards to people having an addiction to Facebook and opting to go ‘cold turkey’ I have seen instances like that during finals and midterm times. For instance, if I have a deadline for a paper or need to study, I will have a friend change my password and not give it back until I complete my work. The lack of will power is fueled by the routine of turning my computer on and immediately going to a social media sight. It is second nature. I would have to disagree with the part about social media being a relationship ruiner because I think that social media has strengthened the bonds between friends who are not necessarily in the same location. It makes it more accessible to catch up and maintain friendships. Social media overall has been blown out of proportions in popularity but when used at a normal amount it is a good aspect of technology in our lives.

Mon amie m en parlé il y a quelques jours, on peut dire que cela tombe bien

The points that you made was spot on, Lauren. I am currently a college students and the majority of my friends who have tried to refuse media was because they feel like they have an addiction to it. Their “consumption” of media was becoming too high to the point that it was starting impede on their productivity of their daily lives. They say that somehow, someway, they are always on their computer, usually Facebook or Twitter, and even though most of the time, the contents are mundane, they surf it for hours. So when they finally realize and accept the addiction to social media websites and its negative repercussion (such as wasting an hour on Facebook rather than writing their paper); they try to to quit it by either deactivating their account or asking a friend to change their password. But one thing that I realized is that social media have penetrated and taken a deeper root in not just individuals, but in our society as a whole. I say this because for those who have tried to refuse media, usually Facebook or Twitter, feels isolated from their social circle not just offline, but online as well. As a result of this, I usually find them right back on their accounts or browsing on another’s account so they can be aware and be included on the topics of conversation. Laura, you also mentioned another point that was quite interesting and quite true: that how once we try to quit media on one platform, we usually find ourselves captivated by another media, just in different from. This happens to most individuals I know who have tried to quit media; they aren’t actually quitting “media” but just one website. My friends who have quit Facebook usually are on the computer for exactly the same amount of time, but just browsing other websites; they are bombarded by media just the same. But the funny thing is that they usually don’t see the irony because they are too engrossed in being proud of quitting one particular site, which to them is the epitome of media, that they make themselves believe that they quit media as a whole.

Thank you for this series of posts, Laura. I found your discussion of how our society could potentially treat social media addiction in the future fascinating (the use of self-help guides, etc.). I personally believe that “Facebook addiction” is very prevalent in American culture, especially within younger generations. Although there has clearly been a shift in what so-called normal internet usage levels are in the past decade, I believe the true measure of someone addicted to social media is if the use of social media impedes their real life interactions with others. I have seen this happen countless times as a college student! There are many people who will use Facebook or Twitter to communicate with friends they could see in real life, but choose not to. Many times these people are within a 5 minute walk of each other. Facebook interactions are much easier and convenient, but I believe the absence of quality “unplugged” in person conversations is going to have a deeper impact for the younger generations. My brother is 10 years old and already owns an iPod touch with internet access, simply so he could keep up with conversations his friends were having on social media. In just 10 years, so much has changed about how we communicate and children today are already adopting social media use rather than planning in person interactions. I think the consideration of labeling and “treating” social media addiction is definitely going to become increasingly important at both the societal and individual levels in the future.

Pingback: Refusing the Refusenicks Paradigm « n a t h a n j u r g e n s o n

It seems to me, unlike many others, you are on the right track here Laura in trying to understand “media addiction” and its resultant social effects. My concern as a teacher most interested in developing needed emotional and social intelligences for complex, human problem-solving, is that media addiction, like all addictions, most harms these types of emotional/psychological paths to true “self” and “other” empathetic understanding.

We know addictions are used to “stuff” feelings. Feelings therefore remain unresolved and poorly understood and eventually – my argument, unfelt or replaced by a drug euphoria or manufactured sense of ‘meaning’. That’s what the drug is supposed to achieve.

I think you are on the right track that the solution can’t be more of the same drug. I also believe it has to do with integrity but more than just “moral’ integrity, more grist for the over-wordy rationalist discussions. I think it has to do with emotional/rational and cognitive/affective integrity. I wrote a piece attempting to get at this issue in world problem-solving in the UN Chronicle entitled “Bringing Human Passion into Education for Sustainability and Bridging Cultures”. But alas, it is more words. Found on the internet.

As an educator, my concern comes down to “Teach your Children Well” and I just don’t think that a rational dominant, science/technology dominant, left-brain dominant word-only form of teaching those children is getting us anywhere but…more addicted. In the classroom, I actually know how to do it differently –by the empathy I bring to learning those children before I ask them to learn these words and disassociated but easily testable facts.

Otherwise, I think we are just setting them up for more addictions. But don’t worry….soon we’ll argue that teachers or “human interfaces” aren’t necessary to teaching, at all. The computers can do that, too. I worry for that world.

Which is why I am so looking forward to the rest of your piece.

Pingback: Navigating Social Media as an Emerging Media Studies Academic « jonescene

Pingback: Media Refusal @ TTW13 | PROF. P-S

Pingback: We’re beginning class in the Library and Media Center today (E-101) | English 101 at LaGuardia, Fall I 2014

Pingback: Today in English 0827, Framing a “problem” | English 101 (0827) at LaGuardia, Fall I 2014

Pingback: Thursday, October 9th in English 101: Framing a Problem | English 101 (0820) at LaGuardia, Fall I 2014