How We Talk About Media Refusal, Part 2: Asceticism

Laura Portwood-Stacer / New York University

In my previous post here in Flow, I wrote about how “addiction” is a common frame for describing media consumption habits that have exceeded normative levels. Basically, when someone seems to be using some form of media too much (like going on Facebook constantly), we speak of them having an addiction. Sometimes we even feel like we ourselves are addicted, when we start to feel dissatisfied by the how large a role certain media platforms seem to play in our lives, or when we feel like we have lost control of our own levels of use.

In this post, I want to continue thinking about “media refusal,” the term I use to describe people’s conscious practice of cutting a certain habit of media consumption out of their lives. As some of the comments on my last post helped to clarify, media refusal doesn’t have to involve the wholesale rejection of media technologies. It can be a more circumscribed practice aimed at even a single platform, as for instance when someone deactivates their Facebook account, but retains their other social media profiles. “Addiction” is a reason often given for engaging in such a practice of refusal; people may feel their use of a media form is pathological enough that they need to “quit cold turkey”—even suffer the pains of “withdrawal”—in order to emerge on the other side a more independent, functional person (examples of this sentiment can be found all over the web; I’ve also heard this kind of thing in my own interviews with Facebook non-users).

The fact that refusal can be, in cases like these, something that an individual imposes on herself, in the interest of self-improvement and problem solving, connects media refusal to the concept of asceticism. Asceticism is defined in different ways, but I like Foucault’s characterization of asceticism as, “an exercise of the self on the self by which one attempts to develop and transform oneself, and to attain to a certain mode of being.”1 Asceticism involves an intentioned “care of the self,” and is thus “a sort of work, an activity; it implies attention, knowledge, technique.”2 We can in fact find examples in popular discourse that prompt users to “problematize” their media consumption, meaning that they are invited first to subject their personal behaviors to ethical scrutiny, and then, importantly, to employ technical solutions aimed at satisfying any problems which are identified.3 The practice of deleting one’s Facebook profile is an example of a technical solution to the “problem” of being too attached to social media; it’s a solution offered by many sites around the web, such as this article which instructs readers on How to Quit Facebook or this one which gives The Top 4 Reasons to Quit Facebook.

[vimeo]http://vimeo.com/13281434[/vimeo]

Fasts and Sabbaths

To illustrate the ascetic character of media refusal, let’s look at some of illustrations related to active non-use of digital media. The practice of reducing one’s media intake is often compared to going on a diet. To give one example, Daniel Sieberg’s Digital Diet is a book devoted to helping you “break your tech addiction and regain balance in your life.” The logic behind the diet metaphor is that you can fight the harmful effects of media consumption by cutting back; like food, it’s only healthy if consumed in moderation. That people sometimes talk about media “fasts” or “cleanses” highlights strikingly the fact that media use is at times supposed to be refused altogether in an ascetic fashion. Social media fasts encourage participants to commit to not using sites like Facebook at all for a given period of time. Like religiously mandated food fasts, social media fasts involve depriving the self of a desired object in the interest of purifying the self and heightening one’s consciousness.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dHcq7s3mDdc[/youtube]

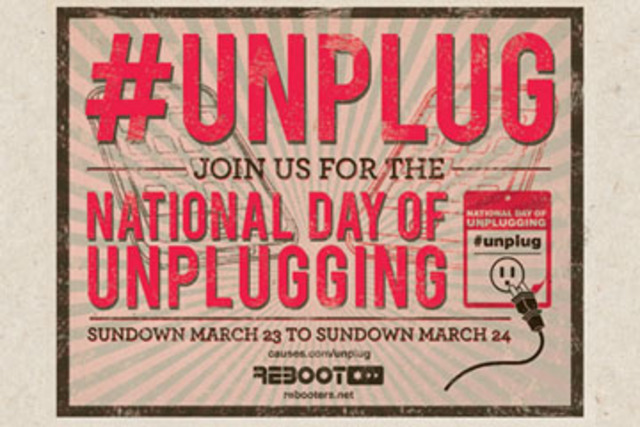

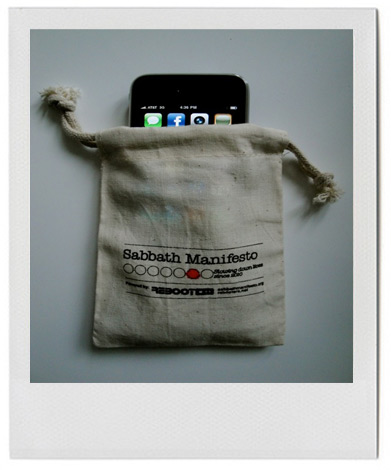

The religious metaphors don’t end with fasting. Periods of time in which media technologies are consciously avoided have come to be known as “Sabbaths,” for many refusers. The Sabbath Manifesto asks participants to spend one day a week, “avoid[ing] technology,” and sponsors a National Day of Unplugging annually. It’s also common to see people giving up Facebook in observance of Lent every year. As with the fasts, media Sabbaths are a way of marking off a time for media refusal, with the intent of achieving an improved quality of life and self.

If media refusal is an ascetic practice of self-care, what kind of selves do we produce when we care for ourselves through media refusal? The most interesting thing to me about the “mode of being” that is achieved through denial of media consumption—if you look at what people say when they talk about quitting Facebook for example—is that it often seems to involve being “more productive.” People describe getting a lot done when they stop wasting time on social media sites. The whole thing smacks of Weber’s “Protestant work ethic” in some ways. But the issue of productivity is complicated by a political economy driven by user generated content, immaterial labor, unceasing surveillance by both corporations and the state, and (if we’re feeling optimistic) participatory democracy through media channels. Being “more productive” while offline, then, may actually simultaneously entail becoming less productive in the new ways that productivity has come to be defined for today’s media-using citizens. It’s hard to say definitively whether media refusers become more, or less, docile or governed (to return to Foucaultian parlance) in the act of opting out.

Many media refusers, instead of or in addition to wanting to become more productive selves, also express the desire to become better friends, partners, parents, and community members through their reduction in media consumption. Might we see these kinds of selves as resisting the logic of neoliberal individualism then? There are clearly contradictions present, since practices of refusal always in some way play into the logic of neoliberalism, as individualized attempts to deal with cultural, social, and political problems (as I talked about in my last post). The ascetic self-care of media refusal is thus a complex phenomenon that merits more attention, particularly with respect to the possibilities it might offer for political resistance and social transformation.

Image Credits:

1. Unplug

2. Cell Phone Sleeping Bag

Please feel free to comment.

- Foucault, Michel.1997. The ethics of the concern for self as a practice of freedom. In Ethics: Subjectivity and truth: Essential works of Foucault, 1954-1984, Volume I., ed. Paul Rabinow, 281-302. New York: The New Press, p. 282. [↩]

- Foucault, Michel. 1984. On the genealogy of ethics: An overview of a work in progress. In The Foucault reader, ed. Paul Rabinow, 340-72. New York: Pantheon, p. 360. [↩]

- Foucault, Michel. 1990. The use of pleasure: The history of sexuality, Volume 2, trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage. See also Binkley, Sam. 2007. Getting loose: Lifestyle consumption in the 1970s. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, p. 131. [↩]

Thank you Laura, for investigating addiction and refusal in more detail. As I read your piece, I was reminded of Sherry Turkle’s book, Alone Together, and her related Ted Talk . While Turkle’s argument focuses on the isolating effects of too much media, it also argues the need to unplug form the “always on” habit and lifestyle, so that the user might even remember what they were supposed to be doing online. Social media is all encompassing and so absorbing that it can confuse the user, who might not even remember the initial reason they intended to log on to Facebook in the first place. Facebook and other social media sites cultivate a “while-I’m-here” mentality — you log on to connect with one friend, but you might as well write on six walls and post some pictures and “like” a bunch of posts while you’re at it. An hour or two later (as The Talking Heads noted), you may ask yourself, ”Well, how did I get here?” I think digital sabbaticals not only force the media user to be “productive” with offline activities, but also to reflect on the nature of what they would be doing if they were online—remembering their initial intentions which might be a bit fuzzy to the “always-on” user.

Thanks for your comment, Rachel. Turkle’s work has certainly provoked discussion among people thinking about social media use – your point is a good reminder to think about the “always-on” user as the flip side of the ascetic refuser!

As both college student and a blogger, I do find that I am one of the culprits who are “addicted” to social media. In response to engaging in “media refusal” and Daniel Sieberg’s Digital Diet, I find that I do agree with the author on how “un-plugging” does not necessarily mean that one is automatically more productive. As the owner of a blog that utilizes Facebook and Twitter to push the content out to readers, I find that the time that I spend “offline,” the time where I may miss an important news item or story that would be relevant to write about. In this digital age, where it is hard to truly “shut-off” as even as you migrate from the computer to mobile devices, there are also Facebook/Twitter/Instagram applications that allow you to be connected 24/7. I do not believe that this solely contributes to non-productivity, because social media is increasingly where Generation X receives their information from.

Pingback: Refusing the Refusenicks Paradigm « n a t h a n j u r g e n s o n

Pingback: Navigating Social Media as an Emerging Media Studies Academic « jonescene

Pingback: Media Refusal @ TTW13 | PROF. P-S