Live Richly, and Prosper

by: Daniel Marcus / Goucher College

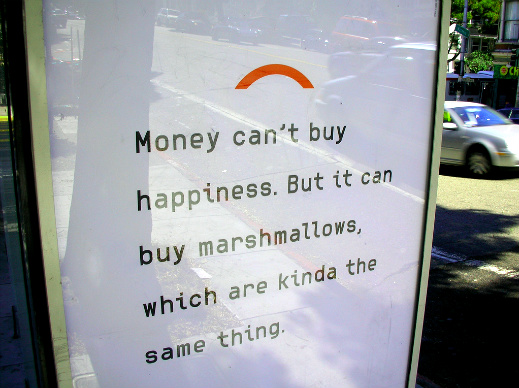

Citibank, one of the largest financial institutions in the country, started its “Live Richly” advertising campaign in 2001, to sell its banking services. The campaign, which has included both television and print ads, reached its peak in 2003 and 2004, and now has been largely replaced, though examples of it still pop up now and then. The heart of the campaign is to urge potential customers to not work too hard, to not consider money to be all that important, to find meaning and fun from activities that emanate from their own creativity, individuality, and relationships with loved ones, rather than through the enticements of consumer culture. A bank is telling us that money can’t buy happiness. Wha?

Of course, capitalist consumer culture has often provided critiques of one aspect or another of itself, usually with the purpose of showing that the solution to the problem it has created is found within its own sphere. Can’t believe you ate the whole thing? Alka-Seltzer will ease your indigestion. Your insurance company is rude and unresponsive? Another one will perform better. Rarely, however, does a mainstay of the system point to a solution or alternative outside the realm of what can be purchased, let alone try to redefine what your goals in life should be, to urge you to forego the rewards of getting and spending.

The campaign did not start out with such a counterintuitive message. In 2001, Citibank’s “Live Richly” ads showed turning points in family life, such as childbirth and children moving toward college, to remind viewers that they should take care of their money; indeed, financial wealth was portrayed as a necessary and crucial component in the successful raising of a family. Only if you were rich (or at least affluent in an upper-middle-class sense), could you live richly.

Soon, however, the ads dropped this definition of the campaign tag line. Citibank, through its ad agency Fallon Worldwide, presented a series of vignettes that pushed themselves through the media clutter by dint of their distinctive look, tone, and message. An older woman sings to her small dog, which howls in return – that’s the whole ad. Another older woman in a colorful dress dances by herself to a jaunty saxophone line backed with a Latin rhythm. Two older women play the acoustic guitar and sing. An older man cuts paper into a pretty design in close-up. Two little kids play in a yard, shown on what looks like 1960s home-movie film stock. In slow motion, a man only partially seen looks upward to a plane in the sky, while alternative-rock guitar plays on the soundtrack. It is a toy plane, and perhaps he controls it, or perhaps not. The locations are simple, either in undefined outside space, in which the most definable element is often a bright blue sky, or within the subjects’ homes. Most of the people are presented in straightforward medium shots (especially those who perform in some way) or odd, partial close-ups. The look is uncluttered, the pace slow or off-kilter. There are never more than two people in a scene; when there are two, they are seemingly related by blood or marriage. Most of the individuals are either small children or babies, or of advanced middle-age or elderly. Most of the guys in between (they are always guys), 30 or 40 years old, accompany children in parental roles.

These scenes are accompanied by words on the screen offering advice and wisdom. “There’s more to life than money.” “The golden years have little to do with money.” “The things you remember most … aren’t things.” “The best moments in life are completely untaxable.” They always end with “Live Richly.” Many of the themes address the need of parents to spend time with their children, rather than working to afford those medical, child-raising, and educational expenses that the campaign initially identified as reasons to do business with Citibank. As a father holds a small baby in the palm of one hand, he is serenaded by acoustic-tinged alt-rock – homey yet contemporary – while he and we are told “If you want to indulge your child, spend spend spend … time.” The two small children in the old home movie are playing dress-up in the backyard, decked out in their own improvised superhero garb and posing appropriately, as we learn that “No kid ever grew up wanting to be Moneyman.” We are urged to rediscover our youthful dreams, and connect with both the child within us and those of the following generation, who look to us for love and attention, not monetary wealth.

Fallon explains the strategy behind the campaign in the oh-so-contemporary terms of brand identity:

“Most consumers’ relationship with their bank/financial institution is strictly transactional and fairly impersonal….Because of this, banks were quickly becoming a commodity vs. brands that inspire loyalty. Citi risked falling into the same den of nameless/faceless banks unless they could connect with their consumers and make themselves a brand that is sought out by their target….Fallon and Citi created a campaign to show that money is a means to have a life[,] not the end game….Thus, by encouraging people to live their priorities and demonstrating their belief that money is a supporting player vs. the central role, they tap into a set of shared values with their customers and prospects.”(1)

In the wake of financial scandals involving some of the largest corporations in the country, and many of the biggest players on Wall Street, Citibank attempts to connect with audiences by demonstrating that it, at least, is one company that doesn’t think money is all-important. In this telling, the bank eschews the intensely bottom-line mentality that led to the ruination of employee pensions and small-investor nest eggs. In the wake of the scandals, it urges a moral revaluation that will set American priorities right, which may be especially comforting to those who lost big in the bubble bursts of 2000 and 2001. It’s nice to know that money isn’t everything when you have just lost most of your paper assets. In addition, Citibank can follow this line of thinking because it is selling retail banking services, rather than the investment advice and brokerage services that many banks moved into in the 1990s. Investors may not be ready to hear so cavalier attitude toward wealth creation from the ones they are paying for investment advice, as opposed to the company that provides mortgage loans and processes their checks.

The happiness and personal priorities that Citibank promotes have distinct , if quirky, shapes. The figures in the ads may share their moments of spontaneity, love and joy with one other person, but no more than that. Individuality and dancing to one’s own drummer are celebrated; any sense of collectivity is absent. Activity is located in domestic, natural space (the yard) or unboundaried public space that is oddly emptied out. These uncanny moments are isolated dreams. They try to connect with the utopian fantasies of the public, as Fredric Jameson has identified as at the heart of capitalist appeals, and are often charming. They celebrate people, but we are directed to limit our appreciation to solitary pursuits.(2)

The campaign has been largely superceded by a new set of Citibank ads revolving around identity theft – the ones in which the voice of an identity thief emerges out of the body of the victim, listing everything that has been charged to an unprotected credit card. The positive idealism of the post-scandal campaign has yielded to a fear-based strategy in which hell is other people. Illegitimate greed can ruin your life, unless you seek out the protection that Citibank provides. It seems that not only social isolation, but social anonymity, is required to just get through the day. The bank, which is one of the largest purveyors of credit cards in the country, has taken steps recently to protect itself too, by lobbying for the new bankruptcy law that makes it tougher for debtors to walk away from credit card debt and restart with a clean slate, even in the case of medical emergency or – get this – identity theft. Now Citibank is out to get us if we face too many of those exigencies of life shown in the early days of the Live Richly campaign, when it advised careful planning. All the more reason to cherish singing dogs, hip-shaking grannies, and the other free-of-charge moments in life.(3)

Notes

(1) Taken from AdForum, where many of the ads can be seen (for a charge), listed under Citibank.

(2) Fredric Jameson, “Reification and Utopia in Mass Culture,” Social Text 1 (1979), 130-148; reprinted in Michael Hardt and Kathi Weeks, eds. The Jameson Reader. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000.

(3) Completed while listening, by chance or unconscious design, to Jonathan Richman’s “New Teller.”

Links

Citi of Fear – What are Citigroup’s Ads Really Saying?

Salon.com – Wake Up and Smell the Subterfuge

Image Credits:

1. Citibank campaign

2. Citibank advertisement

Please feel free to comment.

Pingback: FlowTV | This Issue on Flow (27 May 2005)

Marketing Campaigns as Texts

The Live Richly campaign is one those rare marketing efforts that appears so obviously contradictary to the best interests of its creators that it briefly lifts the lid on just how unassailable the discourse of post-industrial capitalism is, or at least, how confident its leaders are.

In this column, Daniel Marcus shows a way of studying televisual culture that hasn’t been used much on FLOW – examining the ads and promotional content of television by itself as a central text of the medium. Moreover, he doesn’t limit the analysis to one ad, rather several different incarnations of a single campaign, developing over time. Many other campaigns come to mind suitable to a similiar treatment…the MacDonalds “smile” campaign…Target’s pop-art campaign. Even as I think of this as an instructive and novel critical approach, I wonder what the outcome is…creating more observant (eg more cynical) viewers of television? Undermining the ability of advertisers to build these masks? Sometimes criticism seems to bounce right off these sort of reflexive texts. I wouldn’t be at all surprised to see a bank ad that said: “We want your money, we’ll just take less than the other guy.” And I wouldn’t be surprised if that ad worked.

Cynical Ideas About Citibank

First off, I want to commend Daniel Marcus for embarking on a critique of such advertisements, a part of TV that typically seems beyond the considered realm of study, whether because of their status as effluvia or, well, because of their status as effluvia.

But yeah, the recent Citibank ad campaign is not just another cynical ploy. It is a way to reconfigure, via advertising, the economic balance of this country. Rich vs. poor, the lower vs. middle vs. upper class, the debt level of citizenry, all of these as purely economic arguments are beyond the scope of this comment. And yet in the Citibank ads, among others, credit is projected not only as a lifestyle choice (i.e, one chooses to buy something on credit, whether it is a pair of shoes, a car, a house, a college fund), but also as a choice between lenders – Citibank offers living richly (sp), Chase Bank offers individualized plastic differentiators [cards], etc. Then you’ve got the investment bank houses, such as Charles Schwab and E-Trade (to take two disparate examples) advertising personalized and generationalized services.

Obviously, what both of these types of businesses want to do is ultimately to take a percentage of the viewer’s money. But what has changed in this “post-capitalist” landscape is that both kinds of entities want to differentiate themselves, via TV, in such a way that people will call them instead of their local bank, or their employer’s investment company, or their local broker. All of these ads point towards a consolidation of market activity and debt control.

I must admit that as someone saddled by crushing amounts of credit card debt, I simply cannot take these kinds of advertisements at face value. To me every call to “live richly” comes with a high interest rate; every investment ad invariably disclaims their progress with tiny type proclaiming the good year that was the tech bubble.

Yet despite my own biases, I wonder, who are these ads really reaching? Who has the means to “live richly” and yet are ignorant enough to think that a company embarking on a national television ad campaign will help them toward those ends? What kind of people are Citibank, Chase, and others enticing? Is it not the illusion of fiscal equality, the illusion of investment opportunities for all classes, that this kind of advertising plays into? I am prompted to maintain that Citi, among others, is buying television advertising for the primary purpose of coaxing viewers into decidedly unequal relationships of credit and investment. And for that, I can only label this practice as one that takes advantage of the viewer. I do not want to devolve into cliche, but still, caveat emptor.

Pingback: FlowTV | Little Green Men

What is the name of the theme music, with the guitars in the background, kids in 1960’s home-movie film stock? “No kid ever grew up . . .

I would like to know the name of the music from the CitiBank Ad featuring children playing in the yard.

Thank you.

Pingback: All This and Fibre Too! « B2B Marketing Unplugged