Darkly Dreaming of Dexter: If Loving Him Is Wrong I Don’t Want To Be Right

“[Dexter will] charm fellow officers with a doughnut, while away a Sunday with his girlfriend, Rita, or chop up a victim and package their body parts in plastic bags. Hiding beneath the mundane exterior and contrived façade of Dexter, a charming blood-spatter expert for the Miami Police Department, is an obsession with meting out his own twisted brand of justice: stalking and murdering the guilty.”

According to this description, Dexter is both ubermensch and avenging angel. The question is, can he really be both? The character construction of the central protagonist on the Showtime series of the same name raises questions about our “heroes” (or “antiheroes”), truth, power, justice and what means not to be human within a narrative that manages to deal with things that are deathly serious (pardon the pun) with out losing its cool and wry sense of humor. I have watched Dexter since it first premiered on Showtime in October 2006 and, having been a huge fan of Michael C. Hall’s turn as David Fisher, the extremely repressed “good” son (the underappreciated brother) on HBO’s Six Feet Under, I felt both optimistic and protective towards the series before seeing a single episode. I was not disappointed by Hall’s Dexter, which was, with the exception of conveying some elements of carefully controlling impulses and the death tinged milieu, is entirely unlike David. As Hall noted, “David and Dexter are surrounded by dead bodies. Dexter’s a bit more on the supply side of things.” The comment from Dexter’s star as well as those from the creative team and the series’ online fan community made clear something I had suspected even before reading too much about either the series (or about Jeff Lindsay’s books upon which it is based): Dexter is a black comedy…a very black comedy. How could it not be…for real? Its generic sampling includes horror, the thriller, cop shows and domestic melodramedy, integrated in self consciously referential ways that the savvy viewer/ media baby can readily discern. It’s smart, it’s funny and it’s dark: I love Dexter and, if loving him is wrong, I don’t want to right. Nevertheless, I wonder where this strong sense of allegiance comes from and why, as with my previous rabid fandoms (The X-Files, Homicide, Buffy, Firefly, Oz), I sought not to expose friends to the series rather to convert them. In my experience, it takes a certain kind of quality television to inspire proselytizing of this kind—Dexter is simultaneously quite different from the aforementioned fan texts: with the exception of Oz, the murderer is usually the bad guy. Dexter possesses a key element common to a lion’s share of the series that critics, fans and scholars laud as contemporary quality television: a central character that is, at best, morally ambiguous and, at worst, either so pathologically self-centered or self-contained that his/her actions stretch our common lexicon for one who has “emotional baggage” that often ends with blood (and lots of it); in other words, “amoral” or “immoral” don’t seem quite fit the discursive bill.

These ruminations on Dexter are part of a larger project that interrogates how audience expectations of “quality television” began to change with the emergence of the flawed but fundamentally “good men” of network television drama in the eighties and nineties (i.e. Frank Furillo, Hill Street Blues and Michael Kuzak, LA Law; Doug Ross, ER; Andy Sipowitz and all of his partners [with the exception of Bobby Simone], NYPD Blue; Frank Pembleton, Tim Bayliss and the rest of the “murder police,” Homicide ) to characters whose morally ambiguous (or morally relative) actions, drive the narrative and, arguably, the series’ fandom. The Sopranos had Tony, Deadwood had Sweringen, The Shield had Vic Mackey and Battlestar Galactica has Gaius Baltar—then there is Dexter. In her review, “Is it so Sick to Love this Sicko?” Kathryn Flett, after confessing that she had avoided the critical buzz on Dexter, hypothesizes about their content: “Half will be muttering something along the lines of: ‘Omigod, this is a disgusting piece of television made by sickos for sickos that tells us everything we probably didn’t need to know about the moral vacuum In Which We Live Now’, while the other lot will probably be declaring Dexter ‘a uniquely skewed work of darkly comic genius that tells us everything we probably didn’t need to know about the moral vacuum in Which We Live Now’.”While Flett’s take on the critical camps seem accurate, her assumption that the series only “inadvertent[ly]” shines “a bright light on your own heart of darkness” gives neither those creating the series nor those watching it enough credit. Dexter Morgan is an intriguing character—careful, courteous, and methodical and, dare I say it, kind of endearing. As unsettling as I find the last adjective, it is part of the series’ appeal: as stated in “A Thinking Woman’s Killer,” by one Toronto based professional “if you’re being stalked by evil, it’s going to disappear. You’re not going to ask any questions. And then he’s going to show up with lattes. How great is that?” In this series of columns, I want to interrogate how Dexter speaks to contemporary notions of quality television and its appeal—whether through its active play with audience identification in terms of both visual and narrative style, its neo-noir inversion of light and darkness or the extremely strong supporting cast surrounding Hall’s Dexter. Dexter is not the solitary player in the new “quality”—there are others who dabble in ambiguity and, perhaps even relativism, morally speaking.Who is driving this “new” quality? Is it simply that we have become bored with characters who we can understand? Is there some comfort in struggling with the “why” for Dexter’s pathologies—to make the sense of the fact that the horror does not, in fact, make sense? Is this part of larger shifts in taste culture in Post 9/11 America: after large doses of dramatic earnestness, has irony been resuscitated? In “Post CSI-TV: The Ecstasies of Dexter,” Michelle Byers’ discussion of the CSI franchise having “an often humorless belief in science as a route to a truth that will set us free” while Dexter “problematizes the binary structures of good and evil and truth and lies that we are pushed to accept by CSI. … Casting earnestness aside and opening the door to irony, the series highlights its own implication …in the production and maintenance of particular neo-liberal power structures.” Accordingly, the space created for the viewer is not “entirely comfortable (but not entirely unpleasant either)”—a space from which we can muse upon truth, justice, violence and death without necessarily creating a fixed notion of right and wrong. If that seems disconcerting to you, then this might not be the show for you—or it might be exactly the one that you should see.

There is a surprising amount of public discourse circulating around Dexter, whether on NPR or CNN, in The New York Times or innumerable Florida dailies and weekly papers, or in coffee houses, classrooms and living rooms: lots of people are crazy about Dexter—whether it speaks to the infatuation with the character’s inherent duplicitousness experience by some or the disgust at the valorizing of a vigilante killer. So this column ends at the beginning, as it were, with further examination of Dexter, I hope to tease out how his particular performances of identity are in conversation with his “anti-hero” (for lack of a better word) protagonist brethren. I hope these columns will begin a re-examination of quality television—perhaps defining a new concept of contemporary quality television. Although I know that I am in the earliest stages of this study, I truly hope to come to terms with a guiding question has aesthetic, creative and ideological implications in terms of televisual storytelling and, arguably, American popular consciousness. The question: What’s so good about being bad?

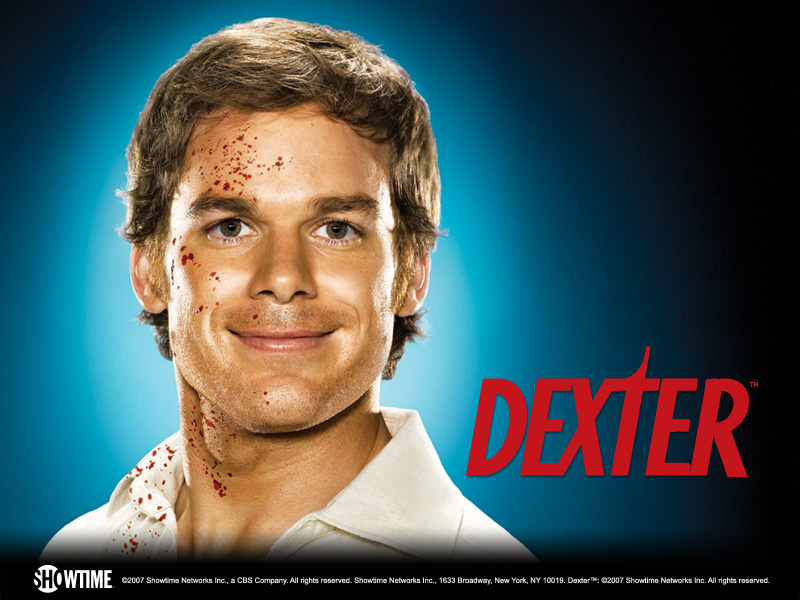

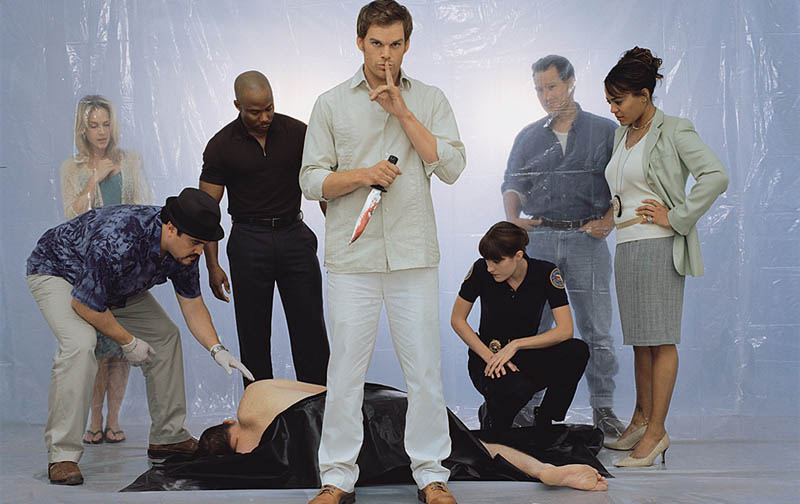

Image Credits:

1. “Dexter” on Showtime.

2. Micheal C. Hall as Dexter

3. The cast of “Dexter”

4. Thumbnail

Please feel free to comment.

This series looks promising. I wonder if one possible reason Dexter is so appealing has to do with the creation of serial killer as celebrity in the 1970s and ’80s. I grew up in a house with a full collection of Serial Killer Trading Cards and VHS copies of the Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Stephen King movies. I would imagine thousands of other people in my age bracket did as well. Might this pop culture familiarity with multiple murderers, serial killers, and horror lead to an audience readymade for Dexter’s particular breed of dark comedy?

Issues of “quality television” aside, the show’s appeal in a country that widely approves of the death penalty, and seems completely ambivalent about the erosion of our civil rights, is not the least bit surprising. Taken from this larger cultural perspective, the show is not the least bit morally ambiguous.

I am an avid viewer of “Dexter” and I’m not entirely sure why. As an opponent of the death penalty and vigilante brand justice, I do have some serious ideological issues with the show. But I keep watching. Perhaps the “quality” that I find in the show is enough to overpower my moral concerns, letting the spectacle overcome the deeper ideological issues I have with the program. That thought is, on further consideration, very disturbing to me. But I often wonder, if Dexter were slaughtering “innocents,” would it be so popular? If it turned out he was luring his girlfriend so as to slice up her and her kids (and get away with it), I will suggest that the show wouldn’t be nearly as popular as it is. Whether this would be because of the lack of a perceived moral ambiguity, or because the show would be going against the grain of popular conceptions of justice, would be good issues to address.

My wife (a Media Studies teacher) and I are fans of Dexter, even though it is rather lost on a second-rank channel in New Zealand. It is not a guilty pleasure either, as it is more than simplistic vigilante/revenge drama. Nevertheless, it is difficult avoiding cross-referencing Michael Hall’s previous role in Six Feet Under.

Thank you for the intelligent queries about this incredible series – you’ve captured the genuine feeling – the ambiguity, the conundrum of Dexter. Rather than giving answers, it posits interrogatives which reflect all of Life’s crucial questions – that is a great deal of its appeal and addictive quality – to watch in wonder and speculate on whether this is moral, immoral or amoral. Do we sit in judgment of this character who had an intensely horrific experience and now tries to deal with it and survive – or do we sit back and enjoy his creative way of handling the baggage that was not of his doing? The only answer is to constantly question and continue to watch this compelling show.

Haven’t we always been fascinated with these heroes/antiheroes…from the woodcutter who does away with the wolf by chopping its head off with an ax because Little Red listened to a stranger and didn’t recognize evil, to lovers of Wolverine who thrill to the italicized word snikt which indicates the Bad-Azz Canadian going into berserker mode, Bruce Wayne as the Dark Knight…from revenge films with Charles Bronson, Antonio Banderas in the Desperado movies, Sweeny Todd, Jack in the Nightmare Before Christmas – we’ve always loved these characters who take control, who come to our rescue, who have been formed by circumstances outside of themselves but have decided to be proactive…it’s just that in Dexter we have a weekly dose of this – we also have a forum to ponder/discuss on a level unlike anything before – is all this inquiry about “What has happened to society that we love Dexter?” much ado about something, or much ado about nothing.

Bambi, nice piece. Let me highly recommend the fan vid, Blood Fugue, by Luminosity — it really captures the psychological horror and disturbance that is Dexter’s mind:

http://luminosity.imeem.com/vi.....loodfugue/

when you guy show sesason 3 and 4 you guys show repeats after repeats start new part 3 and 4

Pingback: FlowTV | Celebrating Television’s Spotty Memory

Most of the reviews on Dexter have overlooked the number one reason, in my mind, that we love this character. We live in a world of hypocrisy, where it’s become an everyday occurrence to hear of scandal, lies, coverups, corporate greed, political shenanigans and betrayal. Our stories of late have all been flawed hero’s, in Dexter we have the opposite–and he’s all the more believable for it.

He’s an ostensibly bad guy, unable to emotionally connect with the world, without remorse or pity–and yet he has a moral code and he follows it. He recognizes and admits his needs and works to ensure they’re met in the most socially productive manner possible.

He’s supportive of others, is an expert in his field, looks after what family he has left, is even willing to sacrifice his brother! He’s a good man who does very bad things to very bad people. Unlike the bad people we usually hear about who do bad things to good people.

He even tells the truth a great deal of the time to others. But thanks to clever writing and people’s willingness to believe the best of good people, they never see the truth beneath the jest.

In a day and age where it becomes less and less likely for evil people to get what they desirve (at least in this life) I think we love to see the bad guys get what’s coming to them. Particularly with out all the bureaucratic bull s#!^ that usually lets them steal, kill or rape again. It’s justice and we want it and they give it too us.

Also the main character deals with being different from everyone else and being alone. Things that we all associate with.

Pingback: A Triumphant Return…or something along those lines. « The Owlery Chronicles

Pingback: The Sins of the Father, the Ubermensch, and Secrets in 312: “Do You Take Dexter Morgan?” | Dissecting Dexter