The D2D Release: Notes on a Burgeoning Market

Amanda Klein / East Carolina University

Looking at Direct-to-DVD (D2D)

Direct-to-DVD (D2D) releases are films that are never shown in movie theaters (or have a small, limited run) and thus receive their primary exposure to audiences through the DVD format. Since 2005 the number of D2D films has risen 36 percent and it is estimated that the D2D industry currently makes $1 billion in annual sales.1 Despite their proliferation and profitability in recent years, however, the D2D label carries a stigma and D2D films are rarely reviewed in mainstream publications. Studies of D2D films (and their predecessors, direct-to-video films) are almost wholly absent from academic discourse.2 Yet the study of D2D films offers an important contribution to the fields of both reception and genre studies.

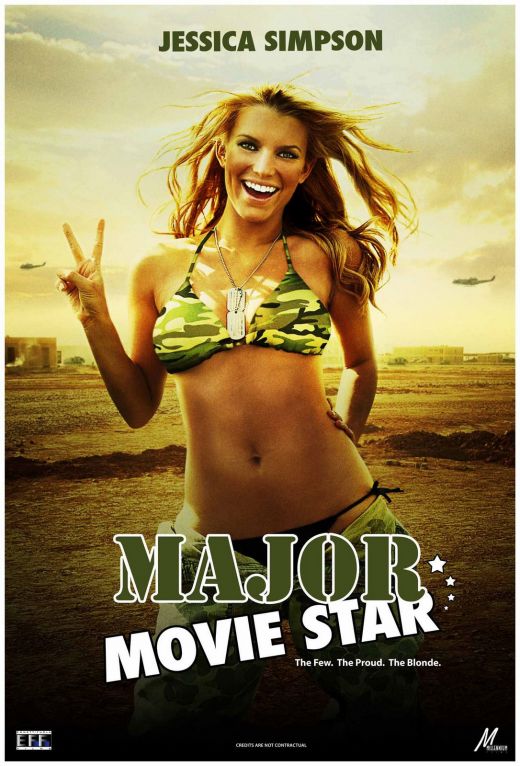

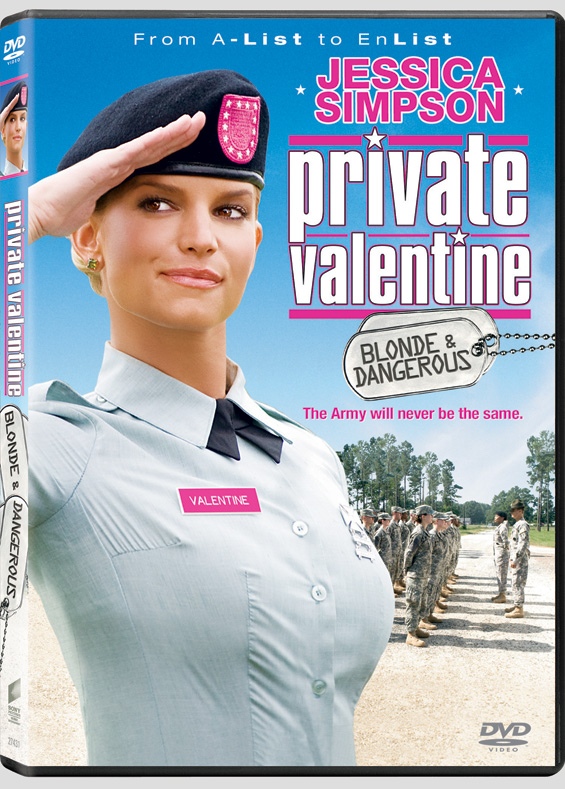

Until recently D2D films have been the provinces of two film genres that are frequently marginalized by mainstream filmgoers: sequels to children’s movies (e.g., Aladdin 2: The Return of Jafar [1994, Toby Shelton]) and hardcore pornography. Indeed, the very concept of the home video or DVD implies a solitary, if not illicit, viewing situation.3 Limited budgets also stigmatize D2D releases. Unlike theatrical releases, which are presumed to have taken time and care in their production, the D2D aesthetic is associated with simple sets, unknown actors and directors and hackneyed plots. Of course, larger budgeted films produced with a theatrical release in mind are occasionally shuttled to the D2D market if the studio feels the finished product is not going to recoup its investment as a theatrical release. The Jessica Simpson vehicle Major Movie Star (2009, Steve Miner), to name one example, was originally conceived as a theatrical release. But due to Simpson’s waning star power and the poor reception of her previous acting efforts (Employee of the Month [2006, Greg Coolidge]), the film was repackaged as the D2D release, Private Valentine: Blonde and Dangerous. Such decisions often prompt derisive press coverage of the film’s star(s) and their careers.

Originally planned as a theatrical release, the Jessica Simpson vehicle, Major Movie Star, was repackaged as…

…the D2D release, Private Valentine: Armed and Dangerous

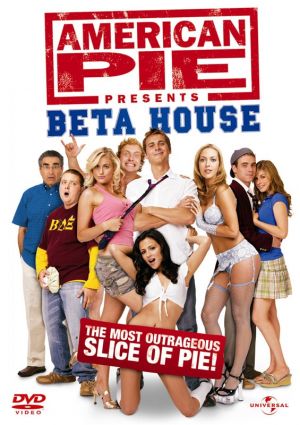

Despite this stigma, studios are beginning to discover the profitability of the D2D release. First, studios are profiting from extending the life of lucrative franchises. For example, the teenpic comedy American Pie (2009, Paul Weitz) generated two theatrically released sequels, American Pie 2 (2001, J.B. Rogers) and American Wedding (2003, Jesse Dylan), retaining most of the original cast throughout. Universal then revived the American Pie franchise in 2005 with the D2D release, American Pie Presents: Band Camp (2005, Steve Rash), American Pie Presents: Beta House (2007, Andrew Waller) and American Pie Presents: Book of Love (2009, John Putch). Although almost none of the original cast appear in these sequels, the use of the “American Pie” name and recognizable logo on the DVD cover signals to audiences that the films will be similar to the original in content and tone. Studios retain the franchise concept and original film titles, but then save money by hiring cheaper, unknown actors to fill in for their A list counterparts.4

The D2D release American Pie Presents: Beta House capitalizes on the American Pie brand by replicating the logo and poster design of the original film.

Studios are also now experimenting with the concept of “parallel content”; they produce a film for theatrical release while simultaneously releasing a film with related content for the D2D market. For example, ten days after Get Smart (2008, Peter Segal) was released in theaters in the summer of 2008, a spin-off film about two of Get Smart’s supporting characters, entitled Get Smart’s Bruce and Lloyd Out of Control (2008, Gil Junger), was released in the DVD market using the tagline “Loved Get Smart? Get More!” Note that this tagline does not promise a novel viewing experience; fans of Get Smart are instead promised a viewing experience similar to that of Get Smart (only without the film’s primary stars). In other words, D2D films bank on the fans’ willingness, or rather, their desire, to watch the same characters, plots, and settings over and over again. Consequently, D2D and direct-to-TV films are arguably the “supreme American genre product: recognizable instances of alike substitutions, repetitions which ring a few character and plot changes but retain a brand identity.”5

As with the exploitation film and the B film, the D2D release must compensate for the poverty of their images and/or the stigma of being “demoted” to the D2D market through some other redeeming factor or exploitable hook; many D2D films promise sensation, particularly sex, gore, violence, and perversity. Too much of any of these things would turn off a mainstream audience and limit the box office returns on a theatrical release, but the point of the D2D release is precisely its limited audience. For example, Lionsgate describes its D2D horror films as “too graphic, too disturbing and too shocking for general audiences.”6 Likewise, while the original American Pie films titillated its teenage audiences with partial nudity—such as a topless Shannon Elizabeth—the D2D branch of the franchise offers full frontal nudity. D2D films can revel in unlimited sex and violence since they are “not required to meet the same rating standards as theatrical releases.”7

The D2D releases’ other exploitable hook is their ability to cater to a specific demographic that remains underserved by the majority of theatrical releases since they can be made quickly on small budgets (D2D films cost between $75,000 and $2 million to produce).8 The historically neglected African American demographic—which is periodically recognized by Hollywood, but only when the industry finds itself in dire financial need—is consistently one of the largest segments of the total movie going audience. Films made for this neglected audience “were among the first to prove this [D2D] market was more than a dumping ground, and they have subsequently paved the way for other genres traditionally shut out of cinemas.”9 Thus, young African American moviegoers are now being courted by independent production companies like Maverick Entertainment and Simmons Lathan Media Group. And many major studios, such as MGM, are also targeting African American audiences by creating smaller production units devoted to “urban films”—the term D2D producers have adopted to denote films aimed at African American audiences.10 These “urban” releases, which run the gamut from black cast comedies, horror films, erotic thrillers, and gangster films, are often direct rip-offs of successful mainstream releases and/or a series of sequels to previously successful D2D titles.

Thus, like the B film cycles of the classical studio era, D2D urban films are capable of exploiting their target audience by attaching African American characters to a variety of genres and cycles. For example, Hood of tha Living Dead (2005, Eduardo and Jose Quiroz) tells the story of an aspiring scientist, Ricky (Carl Washington), who develops a formula to bring the dead back to life after his younger brother is killed in a drive by shooting. Hood capitalizes on the successful zombie cycle of the 2000s but also ensures its success with its target audience by rooting it in the conventions of the urban gangster film. Leprechaun 5: Leprechaun in the Hood (2000, Rob Spera) also exploits its niche audience’s interest in urban gangster films, as well as gangsta rap, the success of the Leprechaun cycle,11 the blaxploitation cycle of the 1970s, and the tongue-in-cheek camp of the late 1990s teen slasher cycle.

Leprechaun in the Hood puts an “urban” spin on the Leprechaun franchise by having its protagonist rap and smoke “blunts.”

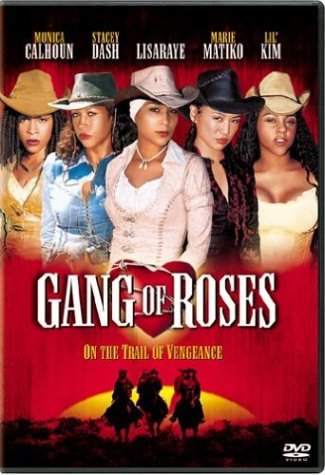

Like their theatrically released counterparts, D2D cycles are tailored to meet the specific desires of their audiences, only on a much smaller scale. By examining the various titles aimed at the African American audience—Bad News Ballers (2005, Brian Shackelford), Gang of Roses (Jean-Claude Le Marre 2003), etc.—we can better understand how production companies envision and construct particular racial, ethnic, and social groups. The Bring it On (2000, Peyton Reed) franchise12 and Christian uplift films (which Maverick Entertainment dubs its “Spirit” line) are two other D2D cycles worth studying in terms of their target audiences (teenage girls and Christian moviegoers, respectively). Furthermore, because D2D films tend to blend several different genres and film cycles as way to squeeze more income out the same plots and characters, I view the study of D2D film cycles as the next logical step in a comprehensive understanding of contemporary film genres.

Gang of Roses is a D2D Western featuring African American women as the gunslingers.

Image Credits:

1. Looking at Direct-to-DVD (D2D)

2. Originally planned as a theatrical release, the Jessica Simpson vehicle, Major Movie Star, was repackaged as…

3. …the D2D release, Private Valentine: Armed and Dangerous

4. The D2D release American Pie Presents: Beta House capitalizes on the American Pie brand by replicating the logo and poster design of the original film.

5. Leprechaun 5: Leprechaun in the Hood puts an “urban” spin on the Leprechaun franchise by having its protagonist rap and smoke “blunts.”

Image source: screen shot from the DVD

6. Gang of Roses is a D2D Western featuring African American women as the gunslingers.

Please feel free to comment.

- Barnes, Brooks. “Direct-to-DVD Releases Shed Their Loser Label.” The New York Times 28 Jan. 2008. 24 July 2009. [↩]

- With the exception of a few pages in James Naremore’s More than Night and one chapter in Linda Ruth Williams’ The Erotic Thriller in Contemporary Cinema. [↩]

- Williams, Linda Ruth. The Erotic Thriller in Contemporary Cinema. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005: 255. [↩]

- Barnes, “Direct-to-DVD.” [↩]

- Williams, Linda Ruth. The Erotic Thriller in Contemporary Cinema. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005: 366. [↩]

- qtd. in Barnes, “Direct-to-DVD.” [↩]

- Barnes, “Direct-to-DVD.” [↩]

- Littlejohn, Janice Rhoshalle “Niche Filmmaking.” Entertainment Today 16 Jan 2004. 22 Nov 2005 . [↩]

- Littlejohn, “Niche Filmmaking.” [↩]

- Hettrick, Scott. “MGM Gets VIBE with Urban Product.” Video Business Online 6 April 2005. 22 Nov 2005 . [↩]

- Leprechaun (1993, Mark Jones), Leprechaun 2 (1994, Rodman Flender), Leprechaun 3 (1995, Brian Trenchard-Smith) and Leprechaun 4: In Space (1997, Brian Trenchard-Smith). [↩]

- Bring it On Again (2004, Damon Santostefano), Bring it On: All or Nothing (2006, Steve Rash) and Bring it On: In It to Win It (2007, Steve Rash). [↩]

Pingback: The D2D Release: Notes on a Burgeoning Market « judgmental observer

Great article, Amanda. What I think is so interesting about D2D is how porous the category is, yet it signifies as such a pejorative regardless. As far as niche filmmaking (mediamaking?) goes, it’s THE mode of distribution — in the case of queer cinema (and international cinema, for that matter) it’s overwhelmingly the primary method of circulation in the US. A lot of D2D movies have that “multiple genealogy” problem — how do you define them generically, place them historically, etc. Good stuff. Mind you, I find them interesting as a phenomenon yet struggle to *watch* them….. You’ll have to point to good (as in “epically bad”) ones.

Very interesting article, Amanda. I’m interested in the consumption of these products. Do people buy D2D films, rent them in stores, rent them from Netflix, or download/stream them? Given HG’s comment, what happens when the mode of distribution changes? In a world of downloading and streaming, will the D2D category–itself extremely porous–disappear? Or become less pejorative? I’m struck by how similar webisodes of popular TV shows are to the “parallel content” model you describe.

HG: I’ve just started researching this topic so I was unaware that much of queer cinema in the US is released D2D–very interesting. If you are looking for a great/terrible D2D film, I would suggest Hood of tha Living Dead. It’s pretty fantastic.

Marianne: I’m not sure about how people are consuming these films (like I said, I’ve just started to work on this subject). My experience with them has been primarily through Netflix, though I know that traditional video rental places like Blockbuster carry a ton of D2D titles. But to answer your question, yes I do think that as more filmmakers turn to this medium (I’m thinking of directors like Soderbergh here), the category “D2D” is going to disappear soon, or at least lose its negative associations. And thank you for pointing out the relationship between webisodes and parallel content–I think that is a spot on observation.

In the still popular, but no longer epic superhero film cycle, animated superhero films intended for older audiences are also finding a welcoming space in D2D. More mature Justice League and Batman films have already worked their way into D2D distribution, as have a few Marvel and Image franchises. These films/series offer longtime comic book fans more mature superhero films that otherwise might never make it to the big screen. As one such fan, I wholeheartedly embrace this form of distribution. Keep spreading the word that D2D doesn’t equal second rate. Great article.

First, I wanted to say that I agree with Michael Thielvoldt about the quality of animation coming out from DC and Marvel D2Ds. For Batman fans, Gotham Knight was a perfect bridge between Batman Begins and The Dark Knight. Furthermore, no one can deny the sheer brilliance of the “Hulk Vs.” DVDs. Big entertainment value, great writing, and a product that is not watered down (per se) for the kids. A joy to comic fans all over the world. Gotham Knight, especially, was a great example of something that was “parallel content” though it was different in form from the live action films.

Second, I’d just like to pose a question. You’ve made the comparison to exploitation and B movies. Many times, those were platforms for younger artists to refine their craft. I’d just be interested in how D2Ds are used (if at all) in that way at all (bringing up new talent). I don’t know if studies have been done on it, but I think I’d be a interesting tangent to explore, and it would impact your article- there would be another reason why the D2D is a market that will continue to grow, namely, as a training ground for younger talent that doesn’t break the bank. Is that even a consideration anymore? Or is the profit goal the sole purpose behind the existence of the D2D’s?

Thanks for casting some light on this sector of the market, as, like you said, it is often missing from “academic discourse.” I would venture to say, D2D discussion is missing from “discourse” in general.

Michael T and Michael L: Your comments re: comic book/super hero D2D further highlights how these films target niche audiences and satisfy them.

And to Michael L, while B films did serve as training for directors on their way up, that doesn’t seem to be the case with with exploitation directors. From my research on the subject at least it seems that exploitation directors and actors (often the directors WERE actors in the films), never made it far from the exploitation circuit. I have not explored whether or not D2D directors have gone on to do theatrically released films, though I do think some of them have done music videos. But that’s something worth pursuing–thanks for the suggestion.

It would be interesting to examine how this dynamic plays out in markets other than North America. I know that in Japan, the rise of D2V (VHS) in the early 1980s is generally cited as being the origination point of the modern hard-core anime fandom, with _Dallos_ (1983) cited as kicking off the trend.

Since the mid-90s, however, it seems as though D2V’s (and later D2D’s) market influence has been collapsing. I’ve heard theories about why this happened, including the rise of satellite TV stations with more lenient content restrictions, or the opening up of the 1am timeslot for TV anime, but that seems an area where further research is warranted. In any event, it is rather clear that D2D anime are much diminished in stature from where they were in the 1980s, often serving as cheap sequels to successful fan-oriented TV anime. _Lucky Star_’s D2D sequel, for example, was equivalent in length to only to a single episode of the original TV series, despite occupying a full disc all to itself.

In the past couple of years, D2D anime seems to have almost ceased to be a market category in Japan, with D2D sequels being bundled with limited-edition releases of the comic-book series that served as the source material for the TV broadcasts. The final volumes of rom-com manga _To Love Ru_, for example, were released in limited-edition form bundled with single-episode D2D sequels to the _To Love Ru_ TV series. These episodes do not appear to have been released to the broader market.

Despite the fact that niche audiences are still the ones being served by D2D, it seems the broader market dynamic here is slightly different from that which you identify in D2D sequels to Hollywood films or D2D one-off films. I think an examination (and verification/debunking) of this difference would be a worthy endeavor.

Everything wrote made a lot of sense. However, what about this?

suppose you added a little content? I ain’t suggesting your information isn’t good., however suppose you added a

title to maybe get a person’s attention? I mean The D2D Release:

Notes on a Burgeoning Market Amanda Klein / East

Carolina University | Flow is a little boring.

You might glance at Yahoo’s front page and see how they write post titles to grab viewers

to open the links. You might add a video or a picture or

two to get people interested about what you’ve got to say.

In my opinion, it could bring your blog a little livelier.

Fine way of describing, and pleasant piece of writing to get information concerning my presentation subject