Twitter Revolution

Vanessa Au / University of Washington

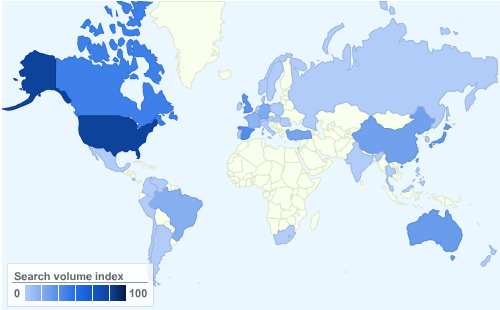

Twitter geographic 2009: Where the tweets are

As the Internet came into popular use in technologically privileged countries in the mid-1990s, scholars began envisioning the web as a potential site of empowerment for the colonized, marginalized, and dispossessed. It was deemed a virtual (or “cyber” as it was often termed) space where such disenfranchised peoples could connect with one another and establish their voices, which are otherwise inaudible in the public sphere.1 While this is undoubtedly an exciting prospect, I will argue that we must complicate our understandings of the role of the Internet, Web 2.0-based social media in particular, in serving these users.

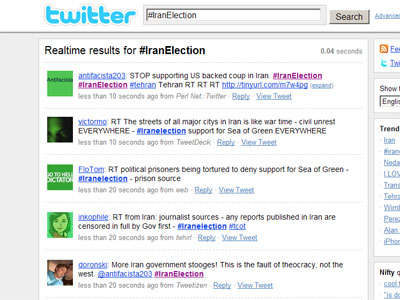

During the Iranian protest of the presidential election in 2009, many people turned to Twitter to share and search for information and links to photos and videos of the protest posted by users in real-time from Iran. Twitter and “status updates” on various social networking web sites2 have become the latest popular means by which people worldwide share and exchange short messages and photos instantly. An article on Slashdot about the protest in Iran proclaimed, “Twitter is providing better coverage than CNN at the moment.”3

Many of the news articles and blog posts about the role of Twitter and other new social media made similar comparisons between traditional news outlets and those enabled by new web technologies. Time Magazine suggests, for example, that “what began as a toy for online flirtation is suddenly being put to much more serious uses.”4 “Real-time, democratically produced live-blogging” a Salon.com article notes, “is quickly becoming a valid alternative to large-scale, ‘legitimate’ news outlets.”5 Sharing news from citizen journalists in the middle of the action has become just the latest in a list of exciting uses for mobile communication and social media.

The bloggers and journalists who authored these articles make several good points. Web 2.0 spaces such as Twitter, Flickr, and YouTube are invaluable for their immediacy, ubiquity, accessibility, and, as a result, their ability to (sometimes) stay ahead of government attempts at censorship. Indeed, many users from around the world can share and repost content in seconds with just a few mouse-clicks and no programming knowledge, and there are countless ways to mask, reroute, and mirror content to side-skirt government censors. However, there are also countless issues of power still entwined in the technologies themselves and also in their use. These issues are often overlooked by writers and bloggers celebrating the democratizing potential of social media, though some at least cite issues such as the credibility of online user reports. But even then, these critiques are usually an afterthought at best. Time Magazine mentions for example, that “the vast body of information about current events in Iran …is chaotic, subjective and totally unverifiable.”6 But these words of caution offered in passing miss larger issues.

Twitter icons colored green in support of Iranian protesters

While the credibility of people posting news and information online is clearly an important issue, it is also one that serves as an easy catch-all critique for commentators eager to celebrate the affordances of social media. But as social media technologies, practices, and structures increase in number and complexity, so must our analyses of the ways in which power is asserted and circulated through them. I point to some distinctly Web 2.0 structures and practices that demand greater critical assessment:

1. Ubiquitous web ranking systems and the hierarchical structuring of web content

While all web content might start out on the proverbial “level playing field” where anyone can put up a web site and establish a voice and presence, Web 2.0 social media sites tend to produce hierarchies of users and content. For example, the ranking systems of web content sharing sites such as Reddit and Digg rely on user votes (or “Diggs) to give content more or less visibility. Unpopular content and user comments are collapsed and hidden from view unless the user clicks to expand it, while comments with many votes of approval inch up to the top of the page.

Even Google uses links to web pages as one way to determine a web page’s “page rank” and thus visibility in its search results. These Web 2.0 features, which purportedly preserve the democratizing potential of the Internet, actually privilege dominant voices. As users participate in determining the popularity of various content and points of view, marginalized voices are crowded out as they are offline.

![]()

Sharing an Avatar article on Digg

2. The sharing/reposting of web content

The rapid sharing of content through reposts and links that is so often praised as revolutionary for the dissemination of news, particularly during such events as the protests in Iran, can also reveal interesting practices of transgression. This Web 2.0 practice, while it increases exposure for those seeking to publicize a little-known cause or point of view, can have the unintended effect of inviting surveillance. People can direct the public gaze to web content, while indicating either their approval, or disapproval of that content. For example, someone who Twitters a link to an anti-racist blog in which they critique the stereotypes and colonialist fantasies enacted in the film Avatar might find their link reposted to Facebook or Digg by the readers of their Twitter stream. Avatar fans on Facebook or Digg angered by the critique might then repost the link along with disparaging commentary, or even an invitation to others to post angry comments to that blog. Thus, people who meant for a potentially unpopular opinion to be read only by a small group of like-minded individuals might quickly find themselves the target of attack because of this rampant reposting of links. Simply put, not only is there is no protection from the panoptic gaze, there is actually greater power for users to redirect this gaze unexpectedly, and with the intention of generating opposition.

3. The colonizing of web space

When people direct the attention of outsiders to content that was meant only to be seen by a particular group or supporters of a particular cause, what can sometimes result is a “colonizing” of the web space to which the content was originally posted. Unexpected visitors to Web 2.0 enabled spaces can turn them into an arena for hostile comments directed at the author of the content, and for heated arguments among visitors to the site. For example, an individual might blog about how to find a hiring company that sponsors H1-B visas, and post a link to the article on Facebook for other potential immigrant workers. Another Facebook user who happens upon this link, and who opposes immigration might navigate to the blog to post his/her racist views on foreign workers. S/he might then post his/her own link to the blog inviting other anti-immigration readers to comment. In other words, the space that was thought to be your own can be reappropriated, hijacked, and sabotaged by those who have oppositional points of view. The rants and debates posted or provoked by visitors with opposing views sometimes even take up more visual space on the web page than the original content. In short, without careful administrative control over user commenting, a Web 2.0 space can be easily colonized. A rush of oppositional readers can take over the space and the power dynamics that take place in offline public discourse make their way online.

In sum, social media technologies such as those embraced during the recent events in Iran can deliver fast, accessible information that can enable the oppressed to skirt traditional power structures such as government censorship, but they can also be complicit in producing an intricate and dynamic system that reifies existing power structures. Web 2.0 thrives on user participation in ranking content posted by other users which brings dominant perspectives to the forefront while crowding out marginal voices and points of view. It would seem that this social media practice might then serve to protect these marginalized voices if they were intended to be heard only by a small readership. However, the popularity of retweeting, reposting, Digging, and other popular Web 2.0 content sharing practices means no one is safe from the panoptic gaze. In fact, once the proverbial spotlight falls on unpopular perspectives, mobs of oppositional readers can take over the web space with their views, and the battles in offline public discourse are effectively brought online. It is becoming increasingly clear that early visions of the web as a site of empowerment for the colonized, marginalized, and dispossessed have not materialized as they were envisioned. Instead, the circulation of power through social media technologies, practices and structures can reproduce hierarchies and complicate the once simple notion of giving a voice to the voiceless.

Image Credits:

1. Twitter geographic 2009: Where the tweets are

2. Twitter icons colored green in support of Iranian protesters

3. Sharing an Avatar article on Digg

4. Front page image

Please feel free to comment.

- Gajjala, R. (2004). Cyber selves: Feminist ethnographies of South Asian women. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.; Mitra, A. (2004). “Voices of the Marginalized on the Internet: Examples From a Website for Women of South Asia.” Journal of Communication, 54(3), 492-510; Mitra, A. (2006). “Towards finding a cybernetic safe place: Illustrations from people of Indian origin.” New Media & Society, 8(2), 251-268. [↩]

- Many Twitter users configure their accounts to replicate their tweets and post them as “status messages” on such Web 2.0 sites as Facebook and LinkedIn. While other Web 2.0 applications, such as Gowalla, allow users to post their status to Twitter or Facebook. This sort of movement and sharing of information is one characteristic Web 2.0. [↩]

- http://ask.slashdot.org/story/09/06/14/183200/Iran-Moves-To-End-Facebook-Revolution?from=rss [↩]

- http:/www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1905125,00.html [↩]

- http://open.salon.com/blog/thomas_rogers_1/2009/06/15/how_to_follow_the_iran_protests_twitter_blogs_and_more [↩]

- http:/www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1905125,00.html [↩]

Good points made. I wanted to add that the term “revolution” in the title of this article and as it has been used recently must be carefully examined. First, the Green movement in Iran is a self-inspired movement. I am not sure if we can really call it a revolution, unless, we consider that it’s a revolution that started with the Constitutional Revolution of 1905-1911 and it has had several peaks such as the “Revolution” of 1979, etc. Either way, it is important to make clear that this revolution is indigenous. It did not start by Twitter or any such social networking site. But, it did get helped by it. In fact, currently, the bulk of news and sharing of information for Iran and the Green movement is happening in Facebook and not Twitter. Twitter is now mainly used for immediate “on-the-scene” and minute-by-minute reporting of a certain rally or demonstration. Facebook and YouTube with their video and audio enabling capabilities have proved to be more trustworthy sources of information on Iran than Twitter.

Thanks so much for reading Kamran! The title actually came from the name of the roundtable at the Global Fusions conference where I presented this paper along with other others from Flow contributors. I quite agree with you!

Pingback: » Petit tour des revues Arthur Devriendt