The BBC Presenter Pay Scandal: The Political Economy of Television Fame

James Bennett / London Metropolitan University

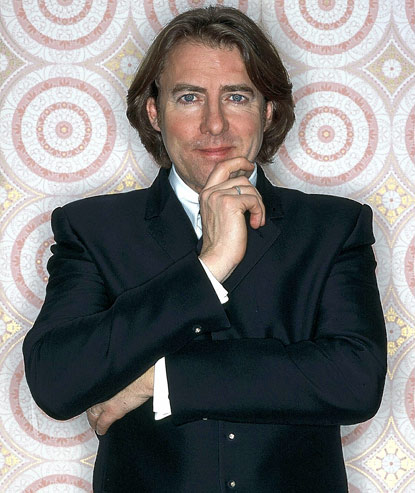

On 7th January 2010, BBC television personality Jonathan Ross announced that he was leaving the Corporation after thirteen years presenting a range of television and radio programs; most notably the late night talk show Friday Night with Jonathan Ross. Less than one month earlier Ross, the BBC’s highest profile and highly paid personality, had offered to take a 50% pay cut on his record £16.9million 3-year contract, which is due to expire later this year. It is clear that the BBC’s decision not to take up Ross’ offer was, as The Guardian’s media correspondents observed, motivated by a desire to rid itself of what had ‘become one of the BBC’s most toxic political issues’. But what does this parting of ways tell us about both the economies of television’s personality system, and what Su Holmes has suggested is the need to understand the ‘possibilities of … public service television fame’.1

For many commentators Ross’ departure from the BBC was inevitable following the Sachsgate affair of 2008, in which Ross and comedian Russell Brand left lewd messages on Andrew Sachs’ (who played Manuel in Fawlty Towers) answering machine as part of Brand’s BBC Radio 2 show. This incident had resulted in a record number of complaints about the program, the resignation of Brand and Radio 2 controller Leslie Douglas as well as the suspension of Ross.2 Whilst undoubtedly, as TV critic Mark Lawson observed, Ross was shorn of some of his cutting edge by being forced to pre-record his shows post-Sachsgate, the notion that his ‘star’ was therefore inevitably on the wane deflects us from closer scrutiny of the political economy of television fame and the role of public service broadcasting in this.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U7IHJ66wj9g&feature=related[/youtube]

Historically there has been a popular incompatibility between BBC presenters and the commercial exploitation and reward of their televisual image. Jerome Bourdon has suggested that star salaries are just one of the key sites through which public service broadcasters must ‘carefully negotiate the popular’, arguing that such broadcasters have only reluctantly given ‘a place to its hosts, but never fully accepted them or rewarded them in proportion to their appeal’.3 For example, Jamie Oliver’s 2002 switch to Channel 4 and What Not to Wear hosts Trinny & Susannah’s 2006 move to ITV have all been linked to the restrictions placed on commercial endorsements by the BBC, whilst the Corporation has always stressed that Ross’ salary was lower than those offered by commercial rivals.

But there has always been a place for highly paid personalities both in terms of ‘popular’ personalities and what we might term the ‘public service personality’. As Espen Ytreberg has suggested, the public legitimacy of public service broadcasters is often communication ‘through persons of authority.’4 Historically figures such as Richard Dimbleby or David Attenborough have personified this type of public service personality with their commercial and cultural value recognized by the BBC. For example, following an offer from the new ITV service in 1958 to Richard Dimbleby, made a counter offer of £10,000 a year for ten years to the man they described as ‘Mr TV’.5 This would have made Dimbley the top earner in UK broadcasting. However, performers who might be understood more firmly in line with the ‘popular’ were also valued by the BBC. Again fearing defection to ITV, the BBC offered [but was ultimately rejected] the first ‘golden handcuffs’ deal to Benny Hill to tie the performer to the Corporation for £15,000/year in 1959—a sum described as ‘far higher than any fee we have ever paid previously to any British Artist’.6

So what has changed?

To my mind the ease with which many, particularly right wing, press outlets were able to depict Ross as a liability to the Corporation has to do with what Paul du Gay has described as a shift away from the bureaucracies of the public sector, which is perceived as a ‘moral danger that breeds dependency, limits growth and suppresses freedom’, to a discourse of self-enterprise congruent with neo-liberal discourses of privatization, personal responsibility and consumer choice.7 As Ouellette & Hay’s study of reality television within this framework suggests, the entrepreneurial self and the private sector is seen as an efficient alternative to the red tape and bureaucracies of the public sector.8 In the depiction of Ross as a liability to the BBC, it was his pay, rather than his behavior, that was attacked as a highly visible example of such inefficiencies.

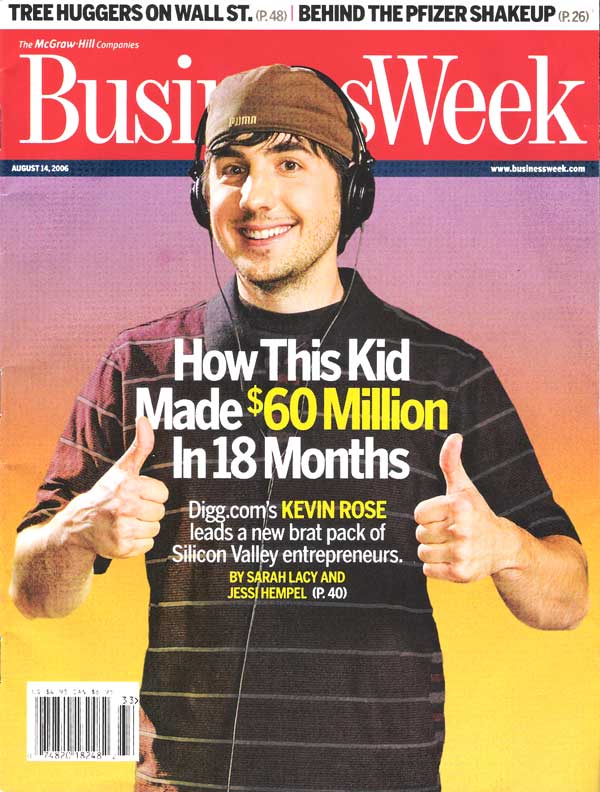

Moreover, in an era where fame is no longer a rarefied commodity, Ross’ pay stands in contradistinction to the radical, supposedly democratic potentialities of contemporary ‘do-it-yourself’ celebrity. Thus whilst Ross is castigated for his pay, Simon Cowell (a figure not unknown for unkind comments to vulnerable performers) is held up as a figure who might revitalize public debate—via a commercial television format—for his entrepreneurial skill in creating formats and pop stars. Similarly a DIY celebrity, such as Digg.com’s Kevin Rose, is celebrated by mainstream media outlets — described as the ‘poster boy’ of web 2.0 culture and ‘The Most Famous Man on the Internet’9 — for his entrepreneurial success in the creation of the site, which had amassed 30million unique users and US$40million in venture capital by late 2008. Much like other DIY celebrities, such as Sandi Thom, Rose’s fame is achieved through self-promotion: mastering a myriad of social networking tools; his Twitter following of 1,159,960 places him well ahead of Ross’ 489,083. Interestingly, Digg.com itself allows users to rate and discuss news stories, fulfilling the ‘participatory turn’ of web 2.0 culture celebrated by new media theorists like Henry Jenkins, but also effectively creating a privatized public sphere congruent with neo-liberalism.

The desire to distinguish the BBC from the perceived inefficiencies and bureaucracies of the public sector was not only evident in the departure of Ross but also BBC Director General Mark Thompson’s attempt to defend the Corporation’s pay structures in its wake. Claiming ‘we are not a county council, we need the best’, Thompson’s comments extended the debate about presenter-pay to the BBC executive, and the economies of public service broadcasting itself. In a year, if not era, ahead that is already being termed ‘austerity Britain’ high profile arguments about the (over)pay of public sector workers, including celebrities like Ross, serve to exacerbate the neo-liberal ideologies of free markets and DIY citizenship—and celebrity—as the antidote to ‘big government’.

Deals such as Ross’ are unlikely to be repeated as the BBC seeks to slash its presenter wage bill. But two significant exceptions remain that shed further light on the political economy of television personalities and public service broadcasting. Firstly, and unsurprisingly, the pay of ‘public service personalities’ such as David Attenborough or Simon Schama—who’s televisual images are congruent with a Reithian notion of public service as ‘improving’, through education and information—have not come into question. More interestingly, at the ‘entertainment’ end of the public service spectrum Jeremy Clarkson—whose image is aligned with conservative ideologies—has struck a pay deal for a cut of the exploitation of Top Gear’s intellectual property rights through the BBC’s commercial arm, BBC Worldwide. Operating within the efficiencies of the global market for television formats, an eyelid has not been batted at this highly profitable deal for Clarkson in these recent debates.

Image Credits:

1. BBC Television Personality Jonathan Ross

2. The New Pathways to Fame

3. Digg Founder Kevin Rose

- Holmes, S. 2007. ‘The BBC and television fame in the 1950s: Living with The Grove Family (1954-7) and going Face to Face (1959-1962) with television’, European Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 10(4): p. 436. [↩]

- See Lisa Kelly’s excellent analysis of the affair and the role of ‘comedy’ in scandal: Kelly, L. 2010. ‘Public Personas, Private Lives and the Power of the Celebrity Comedian: A consideration of the Ross and Brand “Sachsgate” affair’, Celebrity Studies Journal, vol. 1(1): forthcoming [↩]

- Bourden, J ‘Old and New Ghosts: Public service television and the popular-a history’, European Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 7(3): p. 283. [↩]

- Ytreberg, E. 2002. ‘Ideal types in public service television: paternalists and bureaucrats, charismatics and avant-gardists’, Media, Culture & Society 24: p. 759. [↩]

- BBC press clipping, Richard Dimbleby File 1b, BBC Written Archives; BBC Internal memo, From: Head of Talks, Television, To: Outside Broadcasts, Television, Subject: Richard Dimbleby; 30/04/58. [↩]

- Letter from Tom Sloan, Assistant Head of Light Entertainment to Head of Light Entertainment on the subject ‘Benny Hill, dated 18th Feb 1960. [↩]

- Quoted in Ouellette, L. & Hay, J. 2008. Better Living Through Reality TV: Television and Post-Welfare Citizenship, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, p. 23. [↩]

- ibid. [↩]

- Business Week Tech Team, ‘The Poster Boy: Kevin Rose’, Business Week, n.d. 2008, http://images.businessweek.com/ss/08/09/0929_most_influential/18.htm; Max Chafkin, ‘Kevin Rose of Digg: The Most Famous Man on the Internet’, Inc Magazine, November 2008, http://www.inc.com/magazine/20081101/keeevviin_Printer_Friendly.html. [↩]