Editorial: Performing Politics

by: Nick Marx / FLOW Staff

I recently attended a political fundraiser for progressives here in Austin, that glistening oasis of liberalism in the dusty conservative climate of Texas. The state’s governorship (currently held by Republican Bush lackey Rick Perry) is hotly contested and, with mere weeks until election-day, more or less up for grabs. As I sidled into my seat for the evening, the harried apprehension of an opportunity not-to-be-lost was thick in the air. The first speaker of the event, a diminutive and dowdy forty-something, took the stage and huffed deeply. “To borrow from Stephen Colbert,” he said, gripping the podium with both hands and surveying the audience, then emphatically pointing his finger into it, “tonight’s program is all about truthiness.”

I don’t recall much else from the rest of the speech, but what still resonates with me is not the questionable deployment of Colbert’s already-overexposed turn of phrase, but his brusque delivery of it. The speaker seemed acutely aware of both Colbert’s subversive wit and the performative nature of that wit. In the Colbert Nation, after all, each morsel of truthiness is not served a la carte but comes garnished with precisely-mannered gesticulations. What does it mean, then, when Colbert’s entire aesthetic menu, not just his wordplay, enters the political arena on an evening like the one I witnessed? I’d like to suggest that the results could empower disillusioned voters come November.

Several FLOW columnists have already expounded on the mechanisms of satire and parody favored by The Colbert Report much more lucidly than I am willing to attempt here. Their analyses describe that program, alongside The Daily Show, as emblematic of the sub-genre (variously called “new news” or “irony irony”) that lampoons the egomania and presumptuousness of cable news. These ideas are similarly echoed throughout the popular press, which often characterizes the shows as a response to the absurd pseudo-reality propagated by the Bush administration.[1] The focus in both cases seems always to be on the ways in which The Colbert Report and The Daily Show manipulate (and reflect a manipulation of) language, the former with its running feature “The Wørd” and the latter with its snarky graphics parodying various pop culture phenomena. As incumbent Perry recently said of Independent challenger Kinky Friedman after a recording surfaced of Friedman using a racial slur, “Words matter.” But words aren’t everything, and to focus only on the linguistic gymnastics of The Colbert Report is to miss out on a large part of its genius and, consequently, its political efficacy.

A distinction between the respective goals of The Daily Show and The Colbert Report as satire/parody should help illuminate the importance of performance in the latter program. In his much-ballyhooed appearance on CNN’s Crossfire, Jon Stewart hurled invective at hosts Paul Begala and Tucker Carlson for over-simplifying complex issues into sound-bitable quips that further polarize viewers along party lines.

Stewart defended his show as politically neutral, claiming its job was merely to point out the foibles of a foible-prone President and the media that cover him. It’s difficult not to sympathize with Stewart, but he unwittingly provides fodder for the most common criticism levied against The Daily Show by the right — that it’s ideologically vacuous and ultimately trifling. In some ways, though, both sides are correct. If The Daily Show were to explicitly ally itself with any political ideology, it would be guilty of the same rhetorical offenses it so frequently undermines. That is, it makes no direct overtures to liberal impulses, but systematically alludes to them via satiric critiques of dominant political discourses — and is it The Daily Show‘s fault that the dominant discourse of the past seven years has been conservative doublespeak? Stewart and company thus maintain an arm’s-length between themselves and the viewer, fostering critical thought in that viewer rather than force-feeding him easily digestible “infopinions.”

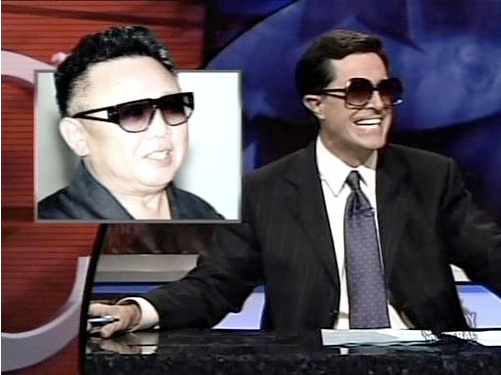

Colbert, conversely, invites viewers right on in for a swift kick to the pants. His strident delivery, combative body language, and repetitive jabs with his conspicuously large pen pack a visceral punch. Pundits are quick to point out Colbert’s physicality as a parody of the braying, Bill O’Reilly-esque newsman persona,[2] but I think something a bit more nuanced is going on. The Colbert Report operates according to the same discursive techniques of parody and satire as does The Daily Show, but Colbert browbeats his ideological agenda into the viewer much more explicitly than Stewart does. Whereas Stewart’s shirking, squinting impersonation of Bush, for example, is a caricaturized slight on the President’s shortcomings as a statesman, Colbert’s comic persona is a carefully constructed and sustained performance that, at this point, has evolved beyond the text/target-text dynamic of conventional parody.[3] Here we arrive at the issue of “getting it,” or, whether or not one reads the Colbert persona as straightforward or satirical. But this is not as important as understanding that viewers of the show, no matter how they read Colbert, are bullied into getting something — the same ideological affirmation they’d receive from Fox News or Air America.

So what distinguishes The Colbert Report from the programming on these outlets? First, obviously, is its satiric impulse, which allows the show to cannily critique a dominant political ideology while explicitly advancing its own. The more urgent point of consideration, though, is the way in which Colbert’s idiosyncratic performance of this satiric impulse dragoons it into political and popular discourses. On his first anniversary episode earlier this week, Colbert proved that he’d finally made it to the big leagues, showing a clip of New York Times columnist Frank Rich discussing truthiness with Oprah Winfrey on her show. And I only wish that Stephen could’ve been with me at the fundraiser to witness his effect on the political arena (though he’d surely complain). The Colbert aesthetic is everywhere, and those looking for a change this November should be quick to embrace it. Candidates accustomed to invoking the wisdom of Kennedy or Clinton might instead consider the wink-wink-nudge-nudge of Colbert, which could accomplish the same emotional appeal but also reward the prospective voter for his media-savvy. If record numbers of young Americans are turning to The Daily Show for their news, here’s to hoping equal numbers of voters, political strategists, and those running for office look to The Colbert Report for inspiration and motivation.

Notes

[1] For a particularly good example, see Mason, Wyatt. “My Satirical Self.” The New York Times Magazine. 17 Sept 2006.

[2] See, among many others, Lemann, Nicholas. “Bill O’Reilly’s baroque period.” The New Yorker. 20 March 2006.

[3] In fact, Colbert’s comic persona has extended into areas of egomania O’Reilly could only dream of. The character’s self-aggrandizement includes the promotion of fictional products such as the cologne Stephen Colbert’s Scorn and doses of his own semen, Stephen Colbert’s Formula 401. He also regularly implores viewers to participate in contests to name things after him, such as a bridge in Hungary and the mascot of the Saginaw Spirit, a minor-league hockey team.

Image Credits:

1. The Colbert Report

Please feel free to comment.

Well, how “meta” can satire get?

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JzoefFhHKyQ