Being in treatment on TV

Jane Feuer / University of Pittsburgh

Psychoanalysts used to refer to the time reserved for each patient as her “hour.” In a similar vein, TV drama is said to occupy an hour. Although both have by now shrunk to about 45 minutes of actual time, the idea of selling yourself or your product by the hour remains common to both. The idea of scheduling by the hour is not the only thing television and psychotherapy have in common. Both are, so to speak, serialized. They unfold over time with gaps in between each session. They are intimate and lend themselves to a two-person dialogue. For all these reasons, television is a better medium than film for portraying the “reality” of psychoanalysis or psychodynamic therapy as psychoanalyst Glen Gabbard and others have noted. In his book on The Sopranos, Gabbard notes that this serialized drama did more than a whole history of films to capture the actual “feel” of a long-term therapy and to portray the analyst as a reasonable if imperfect individual. In an article on Slate, Gabbard waxes even more enthusiastic about the first season of HBO’s In Treatment :

A videotape of an actual therapy session, replete with silence, evasion, and idiosyncratic references to people and places, would bore the average television viewer in approximately 18 seconds. Given that, it’s all the more surprising that . . . In Treatment manages to be both riveting and the most convincing psychotherapy seen on television yet.

I am not saying—although it is true—that television content is overwhelmingly psychotherapeutic. I am not here discussing Dr. Phil’s one hour miracle solutions nor even the kind of pseudo-therapy sought out on medical shows like Grey’s Anatomy (where there is one shrink for all the doctors on the show) or its spinoff Private Practice (where the season cliffhanger left the pregnant therapist under a knife wielded by a delusional patient). I am not referring to that moment on The L Word when two women sought out couples therapy and after listening to them for ten minutes, the shrink said “ You two have absolutely nothing in common” and dismissed them. (One wishes it were that easy in real life.) What is remarkable about In Treatment is that it actually attempts to portray the real thing: long term psychoanalytic therapy—on American “not television.” As a literary genre the memoir of a psychoanalysis has a long history whether told from the patient’s viewpoint or the analyst’s or both. Yet this kind of material has never been thought suitable for entertainment media. You could say that such a resolutely inward focus does not capture the melodramatic tone of much serialized TV. Yet we know that cutting back and forth between two people talking is the essence of television. A camera technique that focuses on the smallest eye movements, that gazes into the soul of one person talking to another has long characterized the shot/answer shot of daytime soap opera, not to mention becoming a staple shot sequence for many primetime melodramatic serials. In Treatment takes the minimalism of the shot/reverse shot to what can be a mesmerizing Zen-like extreme in the therapy sessions.

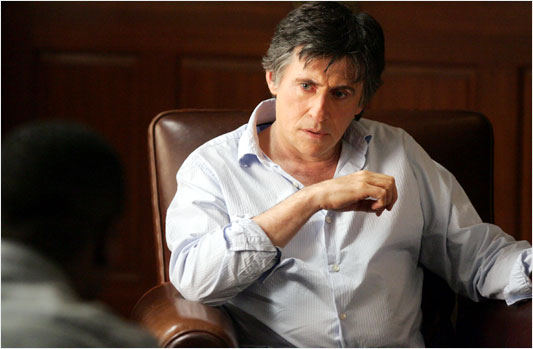

So In Treatment is and is not “real TV.” It seems to be a meditation on the reaction shot at which star Gabriel Byrne is said to be a master. Again, shots of someone listening are stock footage on TV (especially on the local news). But shots of someone listening yet not reacting are the essence of cinema. This gaze is also the essence of psychotherapy, the “sitting up” kind. Paul doesn’t use the couch because that would disrupt the gaze. The show uses the most subtle and refined acting technique. And yet—letting the audience know more than the other character in the scene without using words is another staple of melodramatic television acting.

As an earlier Flow article pointed out, HBO’s In Treatment follows the Israeli version in offering “modular scheduling.” You can follow all five patients or only one of them. In the first season, the five “storylines” overlapped only when Alex and Laura had an affair. This kind of scheduling offers numerous “options” to the viewer, but in some ways the psychotherapy storylines were already modular on The Sopranos in the sense that Tony’s therapy with Dr. Melfi became the focus of the show for some viewers whereas his gangster or family life were the focus for others. After the first season, there was not much of an attempt to integrate Dr. Melfi into the other threads, even the shooting style of her scenes was sparser than the cinematic mise-en-scène of the mini-mansion or the Bada Bing. You didn’t have to like violent gangster narratives to watch The Sopranos, even psychoanalysts could watch it and comment, as they did on Slate. For these viewers the validity and depth of the therapy was the raison d’être for the whole show. This modularity is of course much more pronounced on In Treatment even if the second season seems to be moving the show away from the purity of the therapy per se. Not only that, but the second season is trying to give the show an internet afterlife by providing the viewers with extra-diegetic documents and information. There was a strange hour-long documentary which told us why therapy is good for us by interviewing some therapists and then their patients. More fascinating in terms of breaking the diegesis are the court papers and depositions excerpted on the website and emailed to fans.

For me the most fascinating day is Friday (Gina). Yes, Dr. Melfi taught us that therapists see their own therapist. But somehow the visits with Peter Bogdanovich were a bit too laughable. Paul’s sessions with Gina, on the hand, are searing. If you never fetishized acting or thought it was just the Kuleshov effect, Dianne Wiest will slap you into shape. In terms of getting in touch with unconscious impulses, In Treatment is the next best thing to psychoanalysis itself.

Image Credits:

1. HBO’s In Treatment

2. Gabriel Byrne: Master of the Reaction Shot

3. Dianne Wiest as Gina

4. Front Page Image

Please feel free to comment.

I I have never been drawn in to watching T.V programing like “In Treatment”. For some reason I relate to having some one that I could talk to about my deepest emational thoughts. Gabriel Brynes is more like a therapist than I could ever hope to have. I am additic to this show! I found myself liking the character Laurel most of all. I think the doctor loves the challenges he has in his work, and it makes him a bad father and husband. However, there is nothing wrong with this handsome man except, he needs the same challenges in his personal life as he has in his work. I hope HBO and Brynes returns for a third season!

I. Turner

I have been fascinated with the series since the first “session” last year and have continued with unabated interest. In fact I have blogged each episode with critical commentary from my point of view as a Jungian psychotherapist. The opportunity to look at and reflect on the ethical and treatment issues is great fun.