Strategies of Innovation in ‘High-End’ TV Drama: The Contribution of Cable

Trisha Dunleavy / Victoria University of Wellington

Reviewing American TV drama output for 2008, Heather Havrilesky1 pronounced it “one of the worst years of TV in the last decade” and lamented the apparent return of the risk-adverse commissioning practices of the past, as a result of which, in her opinion, “all of the momentum and promise of the past few years” has receded into “a haze of crappy, unoriginal new programming.”2 Notwithstanding Havrilesky’s prognosis and convincing list of “lackluster” examples, my own view is that any apparent trough for American drama in 2008 is but a blip on an otherwise eventful creative landscape.

Aside from the repercussions of 2008’s writer’s strike, there has been much to celebrate in American drama output of this decade. Indeed, Havrilesky’s ‘golden age’ assessment of successive pre-2008 shows acknowledges an unusual degree of innovation. Focussing on the creative peaks rather than the unavoidable troughs, this column contends that post-2000 innovation in American TV drama has been most striking at the ‘high-end’ of the hour-long series and serial area, this encouraged by the conspicuous success of indicative cable-commissioned examples. Although hour-long drama involves a range of programme types and budgets, the ‘high-end’ descriptor I invoke here refers to drama’s crème de la crème, whose episodes can cost upwards of US$3 million each. This drama is conceptually adventurous and narratively complex, is often created by writers or hyphenates with ‘auteur’ credentials, and uses 35mm film (or its digital equivalent) to achieve a cinematic quality.

Before 2000, mitigated by the market share implications of this drama’s exorbitant cost, the commissioning of ‘high-end’ American series and serials was generally monopolised by broadcast networks with the requisite market share and revenues. But all too routinely, this broadcast drama was creatively constrained by the “safety first” conservatism3 of complacent institutions too terrified to accept the commercial risk of genuine creative experimentation. Broadcast drama has been further limited by daunting expectations of immediate success and then, if delivers the requisite ratings, by sometimes over-blown attempts to prolong its life and profitability (known in the trade as ‘jumping the shark’), one objective of which is to amass enough episodes to maximise syndication and other ‘back-end’ revenues. With such considerations bearing down particularly heavily on broadcast commissions, network timidity continues to set the creative limits on much of TV drama output.

Writers and producers were undoubtedly grateful for significant progressive change in American hour-long drama during the ‘quality TV’ turn of the 1980s and 1990s, which yielded what Robert Thompson4 argued was a second ‘golden age.’ ‘Quality TV’ flourished following the success of breakthrough shows like Hill Street Blues (NBC, 1981-87) which demonstrated an under-exploited link between conceptually inventive, aesthetically edgy drama and the delivery of the affluent audience segments for which advertisers were prepared to pay several times the ‘general audience’ rate5. With Twin Peaks (ABC, 1990-91) among its other ‘classic’ examples, the creative legacy of ‘quality TV’ was to extend and rework conventions in drama concept design and narrative style, to mainstream intertextual and self-reflexive referencing, and encourage production values in a cinematic direction. In these ways, the ‘quality’ turn in American drama answered the challenges of intensifying competition, market fragmentation, and the loss of broadcast audience share to cable. Although ‘premium cable’ networks HBO and Showtime began commissioning original drama as early as 1983 (Edgerton, 2008:6), increased creative experimentation in renewable hour-long drama formats seemed to follow their late-1990s entry into the hitherto broadcast-dominated competition in this costly area of drama. With HBO’s The Sopranos, Six Feet Under and Deadwood finding critical acclaim and luring very large audiences, it was the unexpected success of these and the cable-commissioned dramas that followed – to which the broadcast networks were obliged to respond in their own commissions – that catalysed the broader, more sustained innovation in ‘high-end’ hour-long drama that is now eliciting perceptions of a further round of ‘golden age’ achievements in the current decade.

Innovation in contemporary ‘high-end’ series and serials – which has also been evident in such broadcast examples as CSI, 24, Desperate Housewives, Lost, House, and Boston Legal – has centred on the use of five strategies which, although not new to ‘high-end’ TV drama, have been more consistently deployed in American examples since 20006. These are:

- Inventive ‘generic mixing’ in concept design;

- The profiling of ‘authorial’ input;

- Increasing ‘narrative complexity’;7

- The use of serial narration to foster a ‘must-see’ allure;8 and

- The pursuit of a visual quality that has further reduced aesthetic distinctions between television and cinema.

Helping to disperse these strategies across leading American drama series and serials post-2000 has been an increased willingness by its network and studio investors to accommodate the creative demands of what they regard as ‘star’ producers9 and to support production budgets of around US$3 million per episode10 in the hope of amortising the extra cost in later sales.

As the most successful drama ever produced for cable TV and the most innovative American drama serial in a creatively eventful decade, HBO’s The Sopranos (1999-06) successfully pioneered the above set of strategies to yield a sense of innovation at its peak. Offering a concept with no TV drama precedent, The Sopranos proposal was rejected first by Fox and then by CBS and ABC, before being finally being accepted by HBO11. The sense of novelty that lured viewers to this serial, is grounded in an inventive generic mix whose components include “the gangster movie, soap opera, and psychological drama”12. While authorship claims in long-form drama are often exaggerated, The Sopranos exemplifies the progressive potentials of drama that is able to develop under authorial control. Its ‘author’ was David Chase, the award-winning writer, producer, and director who, having conceived The Sopranos, remained head writer and the “driving creative force” (McDonald, 2007) through its six seasons.

The Sopranos was shot on single-camera film and fully exploited the cinematic regard for visual style – most evident in its feature-like cinematography, subdued and textured lighting and richly detailed sets. Important to the point of difference that this visual quality helped it achieve, was HBO’s decision to invest US $2-4 million per episode, more money than other networks were spending on drama at this time13. The Sopranos demonstrates the full range of textual strategies implied by ‘narrative complexity’14, these including the use of multiple perspectives, dream sequences for psychological revelation, temporal manipulation, and self-reflexive referencing, among other forms of intertextual play. Finally important to the ‘Not TV’ distinction of The Sopranos, is that it was a ‘premium cable’ commission. Its compelling serial narrative was designed to entice viewers to remain with HBO rather than submit to ‘churn’. Accordingly, The Sopranos cultivates ‘must-see’ allure, demanding unfaltering loyalty from its followers. Facilitating the more risqué or violent representations that also characterised The Sopranos, its cable domicile freed the emerging drama not only from anxieties about FCC content rules, but also from the other constraints on a TV drama’s design, content, and style that can be attributed to the context of an advertising-funded broadcast network15.

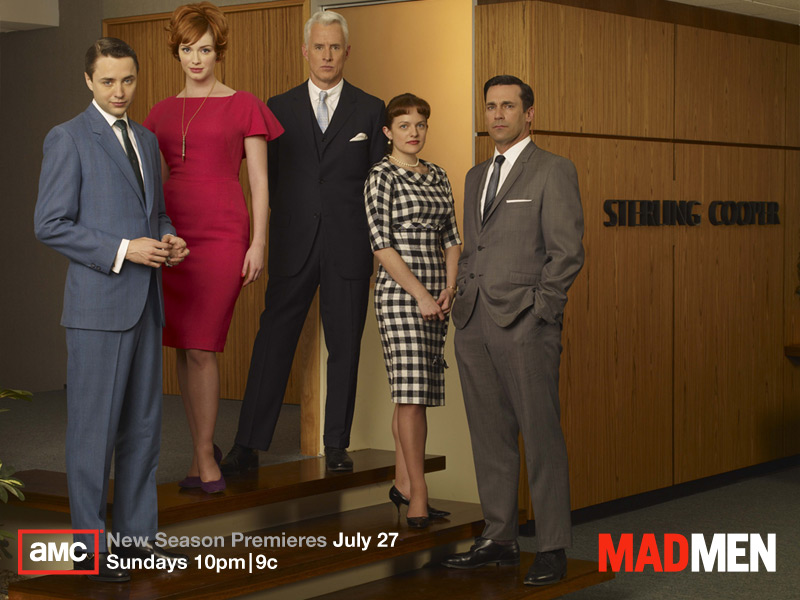

The Sopranos achieved sufficient popularity and profile to draw ‘network-sized’ audiences to HBO and, having done this, raised the stakes on innovation for other networks, placing particular pressure on the broadcast sector. The conceptual originality and aesthetic edginess of ‘high-end’ series and serials appearing after The Sopranos – as exemplified by 24 and House (Fox), Six Feet Under, Deadwood, and Carnivale (HBO), Lost, Desperate Housewives, Boston Legal, and Pushing Daisies (ABC), Dead Like Me, Weeds, The L Word, and Dexter (Showtime), and Mad Men (AMC) – underlines that the creative strategies it so successfully pioneered have since been applied across a broader range of drama-commissioning networks. Deployed to articulate distinctiveness in an evermore crowded, competitive TV landscape and lure hard-to-get, yet lucrative audience segments, innovative ‘must-see’ drama has become a necessity for established as well as for newer networks. Adding to the pressure on leading network providers, is that this kind of ‘high-end’ American TV drama – as the award-winning Mad Men demonstrates – is now being commissioned by ‘basic cable’ networks.

Please feel free to comment.

- Havrilesky, Heather (2008) “The Year the Small-Screen Fell Flat”, Salon, 13 January. http://www.salon.com/ent/tv/feature/2008/12/28/year_in_TV [↩]

- Havrilesky, Heather (2008) “The Year the Small-Screen Fell Flat”, Salon, January 13. http://www.salon.com/ent/tv/feature/2008/12/28/year_in_TV [↩]

- Gitlin Gitlin, Todd (1994) Inside Prime Time, Revised Edition, London: Routledge. [↩]

- Thompson, Robert J. (1996) From Hill Street Blues to ER: Television’s Second Golden Age, New York: Syracuse University Press. [↩]

- Feuer Feuer, Jane (1984) “MTM Enterprises: An Overview”, in Feuer, J., Kerr P., and Vahimagi, T. (eds.) MTM ‘Quality Television’, London: British Film Institute, pp. 1–31. [↩]

- Dunleavy Creeber, Glen (2004) Serial Television: Big Drama on the Small Screen, London: British Film Institute. [↩]

- The concepts of ‘generic mixing’ and ‘narrative complexity’ were first explored by Jason Mittell (2004: 153-7) and (2006: 29-31). [↩]

- The idea and objectives of ‘must-see’ allure in drama were first examined by Mark Jancovich and James Lyons (2003:2-3). [↩]

- Pearson, Roberta (2005) “The Writer/Producer in American Television”, Chapter One, in Hammond, M. and Mazdon, L. (eds.) The Contemporary Television Series, Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, pp.11–26. [↩]

- Higgins Higgins, John, M. (2006) “American TV Rebounds Worldwide”, Broadcasting and Cable, 18 September, pp.18–19. [↩]

- Creeber Creeber, Glen (2004) Serial Television: Big Drama on the Small Screen, London: British Film Institute. [↩]

- Nelson, Robin (2007) State of Play: Contemporary “High-End” Drama, Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press. [↩]

- Edgerton Edgerton, Gary, R. (2008) “Introduction: A Brief History of HBO” in Edgerton, G. and Jones, J. P. (eds.) The Essential HBO Reader, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, pp.1–20. [↩]

- Mittell, Jason (2006) “Narrative Complexity in Contemporary American Television”, The Velvet Light Trap, Number 58, Fall, pp. 29–40. [↩]

- Rogers, Mark, C., Epstein, Michael and Reeves, Jimmie L. (2002) “The Sopranos as HBO Brand Equity: the Art of Commerce in the Age of Digital Reproduction”, Chapter Six in Lavery, D. (ed.) This Thing of Ours: Investigating The Sopranos, New York and London: Columbia University Press and Wallflower Press, pp. 42–57. [↩]

Nice points made in this piece. Clearly, high-end US TV has become the repository of many values traditionally associated with art cinema—bravura montage editing, high-contrast yet subtle mise-en-scène, ellipsis and synthesis, direct address of a knowing audience, and stars chosen for the capacity to deliver lines over headlines. As the glossy, high-art inflected Latin American film magazine La Tempestad puts it, ‘el opio nuestro de cada día’ [our daily opium] was suddenly offering ‘niveles altísimos de exigencia artística’ [the highest levels of artistic achievement]. In the US, 24’s staple audience was the most-educated and affluent demographic group—people not usually associated with the violence and anti-intellectualism of the program’s far-right producers and cash-operated public supporters. Similarly, 30 Rock and The Office maintain their places on schedules because their small audiences include highly-educated, wealthy people.

It’s also worth investigating the internal dynamics within these networks over what to program, and how to do it. Networks like NBC are forever announcing new, failsafe schemes for captivating and capturing the audience. In 2006, it unveiled ‘Television 2.0,’ which was meant to be the end of drama in prime time. In 2008, it declared the return of the ‘8 o’clock Family Hour’ with serial drama throughout the year—this was called ‘The New Paradigm.’ For 2009, it was ‘The NBCUniversal2.0’ or ‘New, New Paradigm’ with less original programming and more reality and talk shows, or what were described in the idiotic vocabulary of managerialism as a ‘margin enhancer.’

Regards

Toby

High-end TV is just better. Networks and even cable TV have FCC regulations and are advertisers are top prority. On HBO, you don’t have that. Cause it’s no TV, it’s HBO. Total creative control is the top priority and it produces many hit, innovating TV shows. Even the ones that don’t really work out like Carnivale. But also in different genres, like comedy with shows like Entourage and Flight of the Conchords. But a thing that HBO does very well that adds on to the cinematic aspects of it’s shows is the realism it presents. The Sopranos was a show that could have happened in real life. However, the best example would have to be The Wire. It’s gritty portrayal of Baltimore’s inner workings (the drug trade, the police, the mayor’s office) is presented almost like a documentary. And it was the best drama that has ever been on TV.

I still believe there is a huge difference in the quality of “high-end” network television and premium cable programming. This difference comes from the focus of the sources. Network television’s goal is to attract viewers so they can sell their products. Using advertising and product placement, network television creates television shows solely to appease their advertisers. They do not care whether a show has high artistic value or is innovative in its content; they only care about making sure people watch their shows and then in turn buy their advertised products. On the other hand, premium cable focuses on creating shows that please the viewers. They choose groundbreaking subject matter and use innovative techniques to keep viewers interested. They main reason for being so creative is so that they produce a quality product. Also, because premium cable channels do not advertise, they are not bound by the usual rules for appropriate material and therefore can be more creative than network television. Additionally, premium channels do not allow paid product placements so content ideas are not influenced by other corporations Network television is all about quantity: the quantity of people watching and buying their products. Conversely, premium cable is all about quality: the quality of its programming so that viewers continue to pay for their viewing experience.

“High-End” TV has definitely made its mark as an influential area for innovated the television drama. In this case, Cable seems to be majorly referring to the upper end extra cost channels, such as HBO, Starz, and Cinemax. These networks, as stated above, are free from certain restriction of the FCC, playing out more like films, which allows for edgier more groundbreaking programs such as the Sopranos. Films are free to experiment, something cables networks like CBS, NBC, and ABC, won’t risk, but with the increasing interest in these extra pay network, basic cable has to keep up. The envelope is always being pushed when it comes to content on television, any episode of Desperate Housewives could contain something completely unimaginable in the past for primetime television. One thing I’ve noticed is, networks unwilling to make big leaps with their programs on their main channel, have other outlets. Fox has the FX Network, generally included in any basic cable package. FX has many show that push the censors to the edge. The show Rescue Me contain sex, drugs, violence, and more sex and has the glossy look of film as well as its movement. Created by Peter Tolan and Denis Leary, well known writers, they take the classic American hero, the firefighter and spin it with a tale of demons and struggle. Quite frequently episode will contain scene of an almost straight pornographic nature, but that the point of the show, to be raw. It also deals with less discussed issues like sexuality, the show deals with openly gay charcter regularly. For the must see factor, episode often end with pending tragedy, like a charcter falling off a building as it cuts to credits. If a show is well received, sometimes the network will move it up into the main channels, or will use the other networks shows as grounds for edgier show of their own.

Thanks for an interesting article. I was wondering if the networks’ interest in “high end” TV can also be linked to the rise of digital recording devices like Tivo. Serial narration is one of the key pleasures of watching high end TV (at least for me it is). But prior to getting my Tivo, I rarely invested in TV programs that required committed viewing–once I got behind on a show I would just give it up (that is why I am only watching Buffy for the first time this year). Do you think Tivo (as well as the trend of putting TV on DVD) enabled these high end television programs with serialized narratives to thrive?

My apologies if this has already been covered elsewhere…

Pingback: Everything communicates: from quality content to quality context » House of Naked