The Play Paradigm: What Media Studies Can Learn from Game Studies

Ted Friedman / Georgia State University, Atlanta

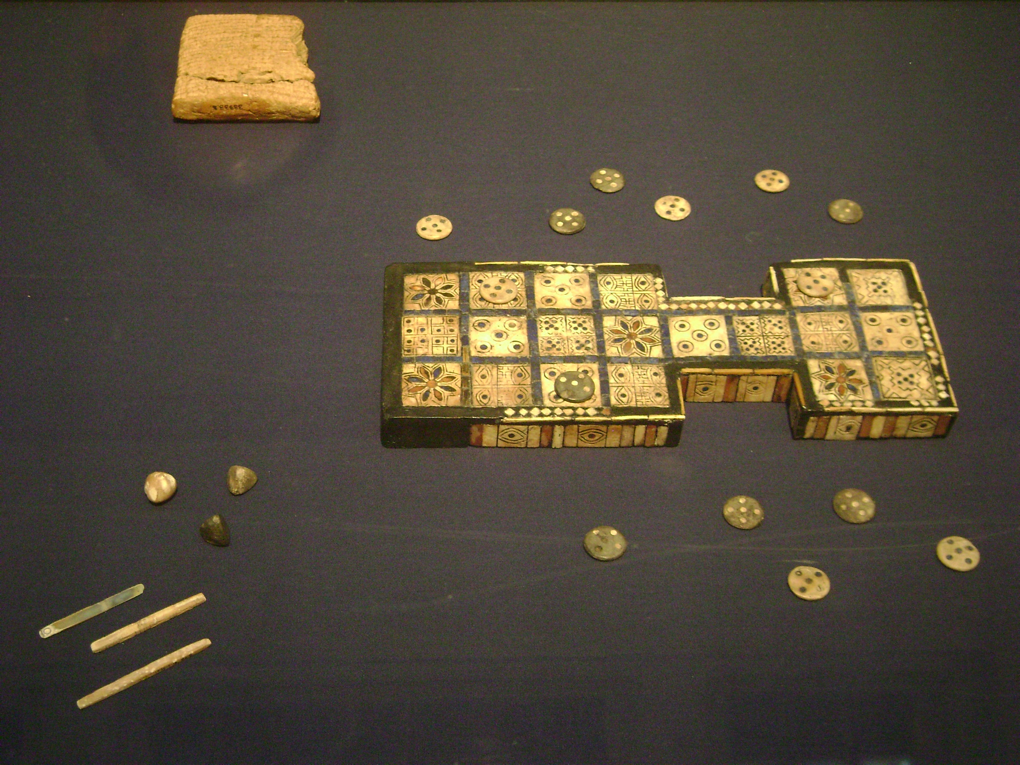

The Royal Game of Ur, one of the oldest known boardgames.

Game studies is a new academic field with some very old roots. Archeologists have found the remains of games dating back as far as 3500 BC. Scholars from a range of disciplines have long studied the history, culture, and design of games. But the rise of video and computer games in the last few decades has produced an explosion of interest in the area, leading to the formation of new journals (Game Studies, Games and Culture, Game Journal, Eludamos, International Journal of Role-Playing, Loading…), organizations (the Digital Games Research Association, the Canadian Games Studies Association), and the inevitable scholarly infighting (the “narratology/ludology debate,” about which more below).

Historically, academic interest in games and, more broadly, play has centered in the disciplines of anthropology (play as culture)1 and child psychology (play as learning).2 But this new interest in games has largely emerged out of the field of media studies (games as texts). Scholars trained in cinematic and televisual textual analysis began to ask, what about this new form of entertainment on our screens? As the game industry has continued to grow, pulling eyeballs away from more traditional media, the question has become impossible to ignore.

Today, game studies, as the baby of the media studies family, has a vexed relationship with its parents. On the one hand, it seeks the approval of more traditional media scholarship. On the other, it wishes to demonstrate its independence. Thus, the aforementioned “narratology/ludology debate.” Game narratologists consider games as new forms of storytelling. Ludologists prioritize games qua games – the formal aspects that make games different from story-based media.3

Myst: story or puzzle?

The rise of ludology as an alternative to narratology marked game studies’ first attempt at an Oedipal break with media studies. But to my mind, game studies has remained too timid in this family romance. Reined in, perhaps, by academic etiquette, game studies has begun to declare its independence from its parents, but it hasn’t yet attempted to usurp their authority. That’s a shame, because film and television studies could use some fresh perspectives. In its explorations in the interdisciplinary wilderness, game studies has picked up some concepts that could help us rethink the paradigms of media studies as a whole.

A good place to start is with the concept of play. Game scholars have turned to play to pinpoint what’s distinctive about gaming.4 We tend to assume that games require active participation, whereas other media require only a passive audience: you watch TV and movies, but you play games. However, upon further examination, this distinction begins to break down. In its broadest terms, we can describe play as any time we lower the stakes on reality to create the safe space for experimentation in the pretend world of imagination. In this sense, the concept of play can expand in all directions. On one hand, to the extent all social encounters are performances, we can describe everyday life as a constant process of play.5 On the other hand, even solitary activities such as watching film or television allow us to dive into imaginary worlds where we can try out different subject positions and social realities.

All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players…

Rethinking media as a form of play offers several promising avenues for us to reexamine some of the core concepts of contemporary media theory, such as the following:

Interactivity. Play transcends debates over how “passive” or “active” spectators are. The model of play takes for granted that all forms of media engagement are inherently interactive, and that meaning is only produced through the imaginative participation of the viewer.

Intertextuality. Play takes for granted the fluidity of multiple media forms. We may transition from watching a movie, to acting it out in front of friends, to re-enacting it in video games, to dreaming about it. These may be different forms of media consumption, but they are all aspects of the same circuit of play, imaginatively reworking the raw materials of story and character.

Aesthetics. Play sidesteps questions of artistic quality, replacing them with questions of usefulness for the imagination, or, simply, fun.6

Realism. Play recognizes that however great the verisimilitude of a text, its ultimate role is to be transformed in the imagination of the player.

Learning. Play is inherently impractical; that’s why it’s not work. But at the same time, play is a dry run on reality. As many educators put it, “play is the work of children.”7 It makes sense that in freelance economy increasingly reliant on life-long learning that not only children but adults find continued value in the challenges of play.

History. The play paradigm allows us to look back on cultural history through a new lens. At a panel on “Televised Sports and its Contexts” at the 2008 Flow conference, Doug Battema suggested that sports programming is at the center of the history of American broadcasting, but is consistently overlooked in scholarly discourse.8 Methodologies designed to study news and fiction have had a blind spot when it comes to more playful genres like sports and game shows.

Narrative. Viewing all media as play upends the narratology/ludology debate. How might it transform our understanding of film structure to see it as just one example of what gamers call “mechanics”—rules designed to structure interactions and frame outcomes? What might a ludology of narrative look like?

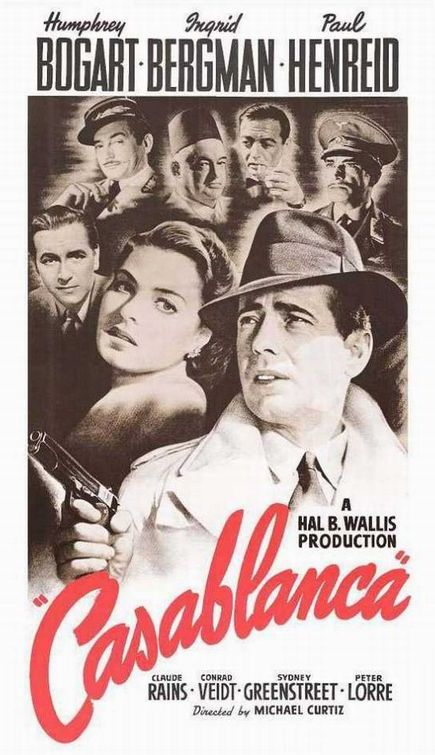

Casablanca: One outcome of the game we call classical Hollywood narrative?

Ideology. What are the politics of play? To the Situationists, play was a utopian alternative to the alienated sphere of work. Edward Castranova gives that vision a Web 2.0 spin in Exodus to the Virtual World: How Online Fun Is Changing Reality, arguing that a generation brought up on games will demand that “real life” be just as fun.9 McKenzie Wark in Gamer Theory offers a gloomy counterpoint, suggesting that play has already become work and work, play, as the gamer jumps through the designer’s hoops to gain a high score in a Sisyphian pursuit indistinguishable from technologized labor.10 Rethinking spectatorship as play, then, offers no immediate ideological answers. But it does reframe the questions in valuable ways, engaging work as play’s implicit other, and then offering the opportunity for each to interrogate the other.

Diner Dash: Playing at work or working at play?

Image Credits:

1. The Royal Game of Ur

2. Myst:Story or puzzle?

3. All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players…

4. Casablanca: One outcome of the game we call classical Hollywood narrative?

5. Diner Dash: Playing at work or working at play

Please feel free to comment.

- See, for example, Roger Callois, Man, Play and Games (Free Press, 1961); Johan Huizenga, Homo Ludens (Beacon Press, 1955) [↩]

- See D. A. Winnicott, Play and Reality (Tavistock Publications, 1971) [↩]

- For an overview of this debate, see the collection First Person: New Media as Story, Performance, and Game, eds. Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Pat Harrigan (MIT Press, 2004) [↩]

- See Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman, Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals (MIT Press, 2004) [↩]

- Along these lines, see Ludwig Wittgenstein’s model of communication as a series of “language-games,” Ludwig Wittegenstein, Philosophical Investigations (Blackwell, 2001) [↩]

- See Ralph Koster, A Theory of Fun for Game Design (Paraglyph Press, 2005) [↩]

- Vivian Gussin Paley, A Child’s Work (U Chicago Press, 2004): 1 [↩]

- Doug Battema, “Televised Sports and Its Contexts,” Flow Conference 2008, Austin, TX, October 10, 2008 [↩]

- Edward Castranova, Exodus to the Virtual World (Palgrave MacMillan, 2007). See also Pat Keane, The Play Ethic: A Manifesto for a Different Way of Living (Pan Books, 2004) [↩]

- MacKenzie Wark, Gamer Theory (Harvard U Press, 2007) [↩]

Great article. While I am very much not familiar with the project and effectiveness of the game studies community, it seems that they have a lot to teach everyone else. Your narrative, framed upon the Oedipal story, is both clever and accurate; the child, most often associated with games anyway, has come of age and now has to teach its parents some new tricks.

I wonder though about one thing. You wrote, “Game scholars have turned to play to pinpoint what’s distinctive about gaming.” If we follow your lead and take play away from gaming and spread it throughout media, don’t scholars now need to revise their formulations? And might a new, useful concept arise from a re-conceptualizing of game studies? I am reminded of the back-and-forth between the AI computer science and philosophy of mind communities about what separates mind and machine; the philosophers set a “only human” benchmark, and the computer scientists write a program that subverts it. The good thing, though, is that with each push-back, we learn a lot more about both fields.

Good point! Play can certainly become a reified concept itself. I think that’s exactly the value of what Wark is doing in Gamer Theory, actually – challenging the pat assumption that “play” is the opposite of “work.” Game studies is in danger of developing its own shibboleths, and could certainly use push-back from other fields.

Despite taking a fabulous (rhetoric of) video games course, I never thought to apply game theory to my area of interest: reality TV. I have always chafed at the idea that watching TV is a static, isolating event; in fact, my personal experience with TV has been the exact opposite. As a child, I bonded with other kids over specific shows; as an adult, those same retro shows bring us together; and, now (and throughout all of my college career), I host TV night for friends and colleagues. For me, TV is not only fun–something I think most theory and criticism overlooks–but it also builds community. However, in my effort to write a dissertation about TV, I forgot about he fun. I forgot how much I love it. I forgot why it’s important to me and why I wanted to pursue this line of research in a discipline that has (largely) ignored television.

But, this article reminded me of all that. I have spent months toiling away on my dissertation, trying to figure out a way to argue that reality TV has actually kept television relevant due, in part, to its sophisticated use of new media; but, I also think reality TV is very good at engaging the audience by prompting them to ask themselves what they would do in those circumstances–in essence, asking them to play along. From a rhetorical perspective, I think reality shows do an exceptional job of inviting viewers to play. Not only do I find this rhetorically provocative, but I think that looking at reality TV from the perspective of play can teach us lessons about other more traditional spaces and texts–such as the writing classroom. As opposed to treating the writing and reading of texts from a consumption/reading perspective, how can we get students to play with texts? How can they extend the invitation to play in their own writing? Your questions have prompted me to view my scholarship and teaching from a fresh perspective and I feel invigorated. I think game studies has much to offer media studies, rhet/comp, and cultural studies, and I look forward to working through some of these ideas myself. Thanks so much!

So this was so useful for me here.