Quality Television, Melodrama, and Cultural Complexity

Michael Kackman / University of Texas – Austin

In 2007, when Terry Gross of NPR’s Fresh Air was discussing the top films of the year, she couldn’t help but insert the HBO series The Wire in her own personal top ten. It wasn’t much of a surprise – The Wire has been a recurring topic on Fresh Air for years, and Gross has interviewed a number of actors, writers, and producers related to the show, some more than once. Of course Fresh Air isn’t the only place where we’ve seen this discourse, but it was especially noteworthy that the ultimate mark of distinction for the show was to detach it fully from its medium of origin, and place it in its “true” aesthetic context – that of cinema.

This kind of maneuver is of course not limited to The Wire, nor to HBO (though more than any network, HBO has branded itself as the preeminent site of quality television, most neatly encapsulated in its claim to, well, not be TV at all). From The X-Files and Buffy the Vampire Slayer to The Sopranos and Lost, we’re in a lively period of some very interesting narrative television.

Both television and the academic discipline that has developed around it have steadily gained legitimacy and accrued cultural capital over the past two decades. The medium – once roundly dismissed as a guilty pleasure or “bad object” – is now regularly discussed in aesthetic terms previously reserved for the relatively more legitimate popular art form of cinema. Auteurism and formalist narrative analysis are resurgent, finding their preferred object in the “mature” complexity of the contemporary serialized prime-time drama.

These evaluative discourses of quality, however, must be understood in relation to the cultural hierarchies that shaped earlier attitudes about television, and which gave the scholarship that explored it its principle political investment. An influential generation of feminist television scholarship took the medium’s low cultural value as a provocative starting point, exploring the overt gendering of its pathologized, culturally subordinate viewers and its mediation of public and private spheres, and finding possibilities for redemptive or resistant readings in its carnivalesque, anarchic character.1 For that generation of scholars, many of the medium’s most compelling possibilities lay not in its aesthetic sophistication, but precisely in its low status. Read in that light, “it’s not television, it’s HBO” is less a declaration of principles than a return to an elitist aesthetics.

In their recent anthology, Quality TV: Contemporary American Television and Beyond, Janet McCabe and Kim Akass mark Robert Thompson’s largely celebratory 1996 book Television’s Second Golden Age as a milestone moment, when discourses of quality television began to coalesce in the media industries, among audiences, and among scholars of the medium.2 A number of other works have emerged recently that explore the quality television discourse, including the anthologies Popular Television Drama, edited by Jonathan Bignell and Stephen Lacey, and Quality Popular Television, edited by Mark Jancovich and James Lyons.3 And while a number of scholars, in these volumes and elsewhere, have reminded us that the discourse of quality television involves textual features as well as particular modes of production and discourses of “quality audiences,” I’m particularly interested in responding here to the development of what increasingly seems to be a neoformalist evaluative aesthetics of television.

One of the more useful and thoughtful articulations of this aesthetic move comes from Jason Mittell, who has recently argued for developing critical modes that better account for contemporary televisual form. In particular, Mittell is interested in what he terms complex narratives, those that blend episodic and serial narrative techniques, build upon extended back stories of both plot and character, are often self-consciously aesthetically experimental, and which promote a particular kind of spectatorial pleasure in the mechanisms of narration itself. To explain this pleasure, Mittell borrows Neil Harris’ term the “operational aesthetic,” which he describes as moments that call “attention to the constructed nature of the narration and ask us to marvel at how the writers pulled it off; often these instances forego realism in exchange for a formally aware baroque quality in which we watch the process of narration as a machine rather than engage in its diegesis.”4

As examples of the form, Mittell offers such programs as Hill St. Blues, St. Elsewhere, Moonlighting, Twin Peaks, The X-Files, Six Feet Under, and Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Mittell is careful to keep some boundaries between narrative complexity and “quality television,” noting that a program like 24 is narratively complex, but also muddled, incoherent, and largely denied the mantle of “quality.” Mittell’s formulation is useful, since he better than most explains the particular kinds of narrative structures that are central to the cultural formation of “quality television” today.

I find it especially curious, though, that the identification and mobilization of the “operational aesthetic” as a primary site of analysis is essentially an intertextual aesthetics (if such a thing is possible). While this particular formation is partly a matter of internal narrative complexity, it’s also undeniably an aestheticization of creative cultural reception practices. The operational aesthetic, as we find it in such programs as Lost or Battlestar Galactica, is both a textual feature, and something fans do to texts. Long before producers were embedding “Easter eggs” and red herrings in Lost episodes and websites, fans were developing televisual literacies via which they extended and rewrote programs; whether explored by Trek slash writers or soap klatches, or more recent forays into “forensic fandom,” the operational aesthetic owes much to the creative animation of the text by audiences. I think we have more work to do to understand how the interpretive labor of certain kinds of audience formations becomes visible and valorized; are American Idol or Survivor spoiler fans any less complex in their interpretive practices than Losties?

More to the point, I’d argue that our pleasure in the operational aesthetic doesn’t come simply from observing the workings of a finely crafted watch, but from a sense that the product of its machinery will be something more broadly meaningful – it tells us what time it is. This is, essentially, a cultural operation, not an aesthetic one.

Quality TV is in part based upon a set of premises about the particular indexical quality that tv narrative is presumed to have with everyday life. Definitions of quality television, both popularly and in our scholarship, depend on a basic formulation that goes something like this: narrative complexity generates representational complexity; representational complexity offers the possibility of political and cultural complexity.5 When we delight in Willow’s witchcraft, or Number Six’s agonizing over spirituality and what it means to be alive, or Omar’s and Bubbles’ tragic misadventures on the streets of Baltimore, we’re not just appreciating narrative craft. Instead, we’re embracing the dream of a more complex world. Maybe, even, a more just one.

All of this, of course, draws us ever closer to melodrama, as both narrative form and index of a kind of cultural longing. What’s really key here is melodrama’s investment in its immediate cultural environs, that is to say, not just its formal play, but its engagement of cultural tensions, instabilities, and anxieties. In fact, it’s melodrama’s simultaneous invocation of, and inability to resolve, social tensions, that makes it such a ripe form for serial narrativization, and which makes it a central, and maybe even necessary, component of quality television. For melodrama, as Christine Gledhill wrote, “draws into a public arena desires, fears, values and identities which lie beneath the surface of the publicly acknowledged world.”6

By saying that we need to reinvoke melodrama as the constitutive force behind much of what we call quality television, it’s not just to remind critics of the culturally low form that embodies much of what they like about current tv. That is not, in itself, much of a point – and I suspect that most of the scholars embracing the narrative complexity of quality tv would be quick to point out that its antecedents lie in soaps and other “low” serial forms (Mittell certainly does). More importantly, though, I’d like to suggest that our ability even to identify narrative complexity and see it as a marker of quality television is itself an act not of aesthetic, but cultural, recognition. Complexity isn’t just something we find in a text; it’s something we bring to a text – and our recognition of certain characters as meaningfully conflicted, their narrative and moral dilemmas agonizingly or beguilingly puzzling, is a cultural identification. I’d like to see us talk more about melodrama and contemporary quality television not just as an ameliorative, cathartic symbolic resolution of social anxieties, but as a mechanism for the registering of political dreams.

This ultimately begs the question of what kinds of characters, settings, dilemmas, can be seen as cleverly complex, deserving of the “quality” label, and which will be relegated to the scrap heap of soapy excess. Which brings me to Lost.

Lost has become an idealized ur-text of television’s aesthetic possibilities, with a complex mythology interwoven with a serialized character drama, all embraced by a knowing, literate fan community. We might productively read the gendered politics of television scholarship against the show’s central narrative preoccupation with paternity, patriarchy, and masculinity. Most of the program’s characters are driven to reconcile a patriarchal crisis: John Locke must redeem his masculinity and rebuild his impotent body after being manipulated by his father; Jack must resolve an Oedipal conflict with his alcoholic father without becoming him; Kate and Sawyer are stalked by their reactions to violent father figures; and the entire island is a trauma site, an experiment in aberrant reproduction. Nearly all of the show’s major characters are haunted by failed or violent fathers; each week’s episodes explore how their individual encounters with fatherhood have or will shape the collective island culture.

I’m a big fan (though not quite at Jason’s level of commitment), but I’m frustrated when we embrace Lost as simply complex quality television without thinking about the relationship of its narrational mode to its gender politics. Two back to back scenes from the recap episode that played at the beginning of this past season neatly capture my frustrations with the show, and with critical responses to it. In the first, Kate and Jack share a fraught moment when, perhaps against his own best judgment, Jack confesses his love for Kate. It’s a dishy, soapy moment, all the more so because of the episode’s Pop-Up Video-style text that comments sarcastically about how the show’s “shipper” fans will respond to the moment.

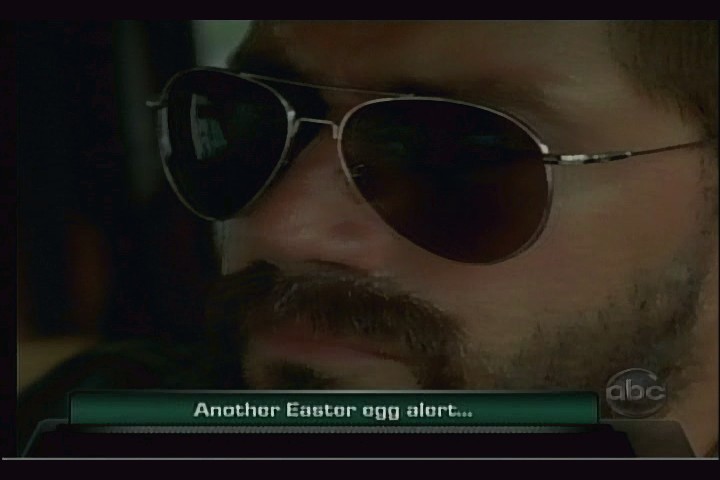

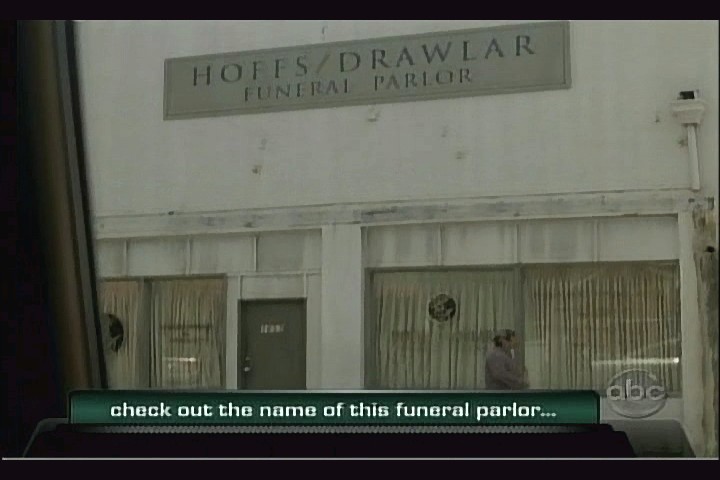

This scene is followed by a flash-forward of an angsty, bearded Jack, roaring around in his Mustang, listening to Nirvana, trying to unravel the mystery of the Oceanic Six. While the first of these two scenes readily confesses itself to be a shameless wallow in weak-kneed, bodice-ripping melodrama, the second signals a turn to the formalist pleasures of the confounding diegesis of Lost, complete with an Easter egg all its own – a storefront sign telegraphs the knowing wink, for it is an anagram of the words “flash forward.”

In order to sustain an interpretation of the show as emblematic of narrative complexity in a way that is distinct from the cultural complexity of melodrama, we have to make two key distinctions: first, we must dismiss the first scene’s sentimentalism as a pander to the “low” pathos of melodrama, and we must read Jack’s process of self-discovery on the streets of LA as inherently more legitimate, a self-aware exploration of the complex world of the program. But are these scenes really all that different? While the first comes with semiotic cues that scream out sentimentality and excess, the second does too – it’s just the more conventionally masculine sentimentality and excess of grunge rock and roaring sidepipes. In both, a melodramatic imagination drives the narrative, and drives our own viewing pleasures: can the characters reconcile their conflicted pasts with their new challenges? Will they find happiness, completion, peace? Will they find self-knowledge, or will they remain tragically haunted by their own demons?

While much recent television scholarship has seemingly moved beyond the field’s roots in feminist media criticism, it often does so by re-embracing the gendered hierarchies that made the medium an object of critical and popular scorn. And while “quality television” is a complicated aggregation of industry discourses, aesthetic norms, audience practices and politics, it’s also, at least historically, a political demand – a kind of Jamesonian hermeneutic dream of being… different. I’d like to urge some skepticism about celebrating television’s new golden age of aesthetic quality. By becoming “legitimate,” we risk eliding our field’s history of politically and culturally invested scholarship. And as the characters of Lost might yet one day learn, the search for legitimacy entails great cost, while illegitimacy has intriguing rewards.

Image Credits:

1. Lost: Quality Television, Melodrama and Culturally Complex

2. HBO and The Return to Elitist Aesthetics

3. Jack and Kate’s Dishy Moment – Author’s Screencap

4. Angsty, Bearded Jack — Author’s Screencap

5. Anagram of the words “flash forward” — Author’s Screencap

Please feel free to comment.

- See for example Lynne Joyrich, Re-Viewing Reception: Television, Gender, and Postmodern Culture. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996; and Kathleen Rowe Karlyn, Unruly Women: Gender and the Genres of Laughter. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1995. Also, of particular relevance here is Jane Feuer, Paul Kerr, and Tisa Vahimaji, eds. MTM Quality Television, London: BFI, 1985. [↩]

- Janet McCabe and Kim Akass, eds. Quality TV: Contemporary American Television and Beyond. New York: Tauris, 2007. [↩]

- Jonathan Bignell and Stephen Lacey, eds. Popular Television Drama: Critical Perspectives. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005; Mark Jancovich and James Lyons, Quality Popular Television: Cult TV, the Industry, and Fans. London: BFI, 2008. [↩]

- Jason Mittell, “Narrative Complexity in Contemporary American Television”, The Velvet Light Trap #58, Fall 2006. p. 35. [↩]

- This little equation is at the center of Kristen Lentz’ reflection on the early ‘70s moment of quality and relevance. She writes that “the discourse of ‘quality television,’ associated as it was with feminism and improved images of womanhood, attached this feminism to a self-reflexive critique of the medium of television itself.” Through the discursive practices within and around MTM Enterprises, as Lentz succinctly put it, “Television thus enfolded feminism into the project of advancing not the female subject, but the ‘subject’ of television.” “Quality vs. Relevance: Feminism, Race, and the Politics of the Sign in 1970s Television. Camera Oscura 15:1, 2000. p. 47. [↩]

- Christine Gledhill, Home is where the Heart is: Studies in Melodrama and the Woman’s Film. London: BFI, 1987. p. 33. [↩]

Hi Michael

I thought I should point out that my article in that book was not celebratory and that I have always argued that melodrama feeds both quality drama and soap opera. And I am NOT a fan of Lost. You are right to point out all the ways in which that cult is misguided.

Yours, Jane

I’ve been looking forward to seeing this in written form, Michael! A lot to chew on here, with long-lingering debates about “quality,” “complexity,” gender, genre, class, cult, and mainstream. Not to echo completely the calls from Flow to study According To Jim or Two and a Half Men more closely, but I think the overall point of that critique is important: in our focus on the Losts, Wires, and BSGs of the world, what are we gaining, and what are we missing?

I’m all for an “aesthetic turn” in Television Studies (as it has been variously called), but, like you, I’m wary of its implications. As long as we recognize that aesthetics come from multiple somewheres (creative practices, industry norms, viewer practices, cultural politics, etc.), and expand our purview beyond the same half-dozen shows, then I think we can productively and provocatively advance this line of analysis.

Good piece, Michael. I like that you apply the “cultural brakes” to the runaway train that is the aesthetic debate in current media studies circles. As one who worries considerably about the implications of this debate (What does Foucault say? Something about why do away with the categories only to then reinscribe them again at the end?), this seems an apt rejoinder to the narrative complexity argument that still keeps what’s useful about it….

Great piece, Michael. I agree the unexamined equation of quality with complexity is a particularly strange move for television

studies to make. It reached its apotheosis in the Steve Johnson’s “Everything Bad is Good for You” book from a few years back, with

its rather hilarious charts demonstrating how much more complex and thus worthy “The Sopranos” were in relation to “Starsky and Hutch.” Complex TV is apparently better because it forces you to make more neural connections, in the same way that video games are good for hand-eye coordination!

I think much of this impulse comes out of TV studies rather consistent desire to see itself as a misunderstood, maltreated victim–an impulse that sometimes leads us to embrace various hybrids of naturalism and modernism to “prove” TV is just as important as film and the novel. But that’s ultimately a doomed strategy, I think, much like trying to fit in at a country club that never wanted you in the first place. HBO is right–they aren’t television–they’re just bad art cinema.

Great piece, Michael, and one that requires a much more in-depth response than I am going to be providing with this comment. I just wanted to say that I’ve been of two minds about the “few great shows” issue plaguing much of television studies. On the one hand, it’s helpful to have the consensus narratives I’ve talked with David Thorburn about often, in this case not for building national awareness of common issues and to have a common text that we all share, but rather to have a common text scholars can use to illustrate important themes for the field in a language all can understand. On the other, the creation of “quality television” as a designator defines as “good” a narrow form of artistic markers.

As you know, I focus on researching–and enjoy watching–shows that don’t have seasons, or end dates. Soap operas, professional wrestling, late-night talk shows a la Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert…they defy the markers of quality television. I’d argue that they are very “narratively complex,” but that complexity takes place in a variety of other ways…in the way these shows add value to viewers for the layered memories of seeing a character for years or perhaps decades; in the way subtext is played that relies on complex relationships amongst a large ensemble of characters; etc. To Jeff’s point, narrative is far from the only way for a show to be “complex.” That doesn’t mean that narrative complexity isn’t worth highlighting; but it can’t become synonymous with complexity itself, at the exclusion of emotional complexity, psychological complexity, relational complexity, social complexity, and on and on.

I love your take on operational aesthetics being an external force, Michael, in that it forces us to think about where these dynamics lie. I’ve argued that soap operas are social texts whose resonance with the audience only takes meanings in the relationships and dynamics that are built around them. I think that these reception practices demonstrate that texts seem from “the outside” as redundant and “soapy,” to use the phrase you did–with plots that are often predictable and with a low cultural status–nonetheless generate considerable complexity through their focus on emotional content, character relationships, and the long-term memory conjured up in the subtext and unpacked by viewers amongst themselves.

Lest I anger Jeff by referencing the taboo “fan studies,” I want to clarify that I’m not talking about a narrow definition that involves fanfic, fanvids, and other “active” components but would argue that talking about a show, proselytizing to others, archiving favorite moments, etc., is a lean-forward, active approach.

I think that, in terms of questioning whether we are making T.S. Eliot’s mistake and canonizing a medium that in fact thrives on its diversity and freedom, we need to consider the question of effort. I speak of, say, a show like Heroes: a show that wants to be “great” by this definition, has occasionally shown flashes of potential, and yet at the end of the day you won’t find a TV critic or, likely, a TV scholar willing to defend it as a member of any sort of elite club of television series.

Of course, as Sam notes in the last comment, the question of viewer interaction has NBC convinced that Heroes is still a hit: because the fans are talking about it, and packing into Comic-Con halls to scream at their favourite stars, it is considered to be a flagship series even as ratings continue to dwindle and they’re forcing out showrunners in an effort to create change. The irony, of course, is that the requirement for viewer action might be why it, and many mythology driven science fiction/fantasy series have failed: while certain viewing circles have embraced the internet as a place to engage with their favourite shows, yet others are frustrated that in order to get the whole story they have to log online and read the latest Heroes comic book. Quality be damned, Heroes’ ratings were going to drop regardless when the casual viewers latching onto a cultural zeitgeist fleed the coop by the time season two came around.

(And as an aside as it relates to Heroes, rumours about how they plan on revamping that show after a failed third season creatively involve a lot of the above rhetoric as it relates to being focused on individual characters – gone are the days, apparently (and hopefully), where fixing a problem meant giving it a power or sending it backwards, forwards, or sideways in time)

It is these shows that straddle that line between melodrama and the “great” narrative complexity which are often most fascinating, those that operate within one sphere but slowly leak into the other when either required or suggested. When Law & Order makes a significant casting change (either a new arrival or a departing favourite), there’s a sudden tonal shift: gone is the straightforward procedural structure, and in its place we find a case that’s shockingly personal, shockingly explosive, or shockingly sudden. When Elizabeth Rohm’s ADA responded to her firing with “This is because I’m a lesbian, isn’t it?” it was a glaring attempt at being this complex narrative, wishing to convince viewers that all along they had been watching a complex investigation into homosexuality at the prosecutor’s table.

As someone who admittedly watches a great deal of “melodramatic” television, I have a certain appreciation for it: while I have been driven away from the more procedural shows due to their lack of anything even approaching narrative complexity, in blogging about shows like ABC Family’s Greek, or The CW’s Gossip Girl and Privileged I often find myself finding depth in fairly surprising places. All of these types of shows have their base storylines, the highly predictable and generally simple notions of teenage relationships, and yet they maintain interest by also presenting characters and situations that feel more realistic. While I’m unlikely to write 4000 words about the Gossip Girl finale, I don’t think that this implies there is nothing to write about: even if these shows trade controlled complexity for seat of the pants narrative rollercoaster, they are still entering into a discourse that is a reflection of viewer interaction, cultural developments and (at some points, at least) an intelligent view of younger viewers.

And that’s all the rambling I’ll do for the time being, ironically time made when the melodrama of Grey’s Anatomy reminded me of the melodrama of Alias’ highly contrived third season.

Pingback: Dexter and emotional complexity « Just TV

I posted a much-delayed and slightly off-topic response to this essay on my website – be warned that it focuses on Dexter and reveals some key season 1 spoilers…

I find the descriptor “Quality TV” troubling for several reasons. The first is simply the inevitable confusion that results from trying to use an imprecise and widely-used adjective to provide a normative model for what “rewarding” television should be. Another reason for my displeasure with this term is the implication that if a program does not meet the formalistic criteria defining “Quality TV” then it must therefore lack quality altogether, rather than be found lacking a certain quality (which makes it “Quality TV”). The third reason is that the “Quality TV” conversation seems to me, an admitted outsider, an effort to fool us all into thinking that the emperor (the academy) has new clothes, when in fact the debates over “Quality TV” are simply a rehashing of the age-old war between the genres for respect. The final reason for my displeasure follows from the previous three—namely, that it excludes from consideration whole genres of television programs and the singular examples within these genres which stand out.

Take Michael Kackman’s essay on Flow.TV, for example. I wondered whether my own off-balance, squirming feeling in reading this essay was a reflection of Kackman’s own discomfort with trying to define what it is that qualifies a show for the “Quality TV” label. After re-reading his essay a few times, I still couldn’t tell why he believes the Lost series qualifies (or if he even does, though he clearly wants to).

I do know, however, that Bill Moyers Journal wouldn’t qualify. That much is clear to me. Since Kackman’s criteria automatically excludes all programming that is not dramatic (fictional), most that is not melodramatic, and probably anything which is not “cleverly complex” however defined. I am not going to be so bold as to assert that Bill Moyers Journal is “Quality TV,” because I haven’t yet found it to be sufficiently distinctive (in presentation, content, or social import) relative to its talk show peers to deserve such a label. But I do have serious problems with its being automatically excluded from consideration on purely generic grounds. I would suggest that a number of PBS series such as Frontline and Nova are deserving of the “Quality TV” label in the sense of being distinctive television. And while the timeliness of the Frontline series may often prevent it from having a long shelf-life as “must see”, “must talk about” TV, such is not the case with the profoundly important series Eyes on the Prize. Oh, yeah, that’s non-fiction. It’s not “Quality TV.”

The criteria for “Quality TV” should be much more inclusive than its narrative complexity and resonance with everyday life, or in Kackman’s phrase its “engagement of cultural tensions.” It should embrace any television program that rises above its peers in a significant way, demands and holds our attention on the basis of the text alone and not on the muscle of its marketing, and makes itself worthy of deep conversations over a long period of time. No program should be automatically disqualified.

Hi John – I think you should consider the fact that Kackman is analyzing narrative TV as are all the scholars he refers to, not news/political shows.

Somehow missed this when published, but it’s great, Michael. Your move to link the emergence of this latest turn to “quality” to a move away from the strong feminist origins of much of TV studies is spot on.

After reading this article, I examined one of my favorite sitcoms within the context of quality television. It did not make the cut.

While The King of Queens is engaging and comical, it hardly qualifies as quality television. According to the Michael Kackman article, “Quality Television,” quality television operates on “complex narratives.” The King of Queens fails to meet the standards of a complex narrative in that it does not draw attention to the mechanisms of the narrative, rather it immerses its audience in the obscurites of fast-moving scenes. These scenes are obscure because they operate for the purpose of temporary pleasure; immediate laughter and can be quickly forgotten.

In this immediate pleasure, an “operational aesthetic” does not exist . I rarely ask myself “How did the writers pull this off?” when watching this sitcom. I have a clear understanding of the characters and can easily disengage myself from the plot as the punchlines move quickly and are a central proliferation to the function of the show.

Furthermore, The King of Queens does not qualify as quality television because it does not call in to question or examine a larger theme/idea. Unlike “Lost” which consistently examines ideas of fatherhood, isolation and desperation, The King of Queens fails to establish importance within a defined concept and /or challenge that concept. This is not to say that the sitcom is “themeless.” The show certainly touches on points of class and marriage, but falls short in examining these realities in a systematic and literary fashion.

The show often concludes with a final punchline, which though not necessarily its objective, can easily detach the audience from larger themes relative in the program. In this, I believe producers stay true to the show’s core objective…to encourage laughter within the frame of simplicity.

The King of Queens, although stars a Jewish couple, does not employ the tactic of Jewish humor. The show again veers away from making a political statement. While also featuring an African-American family, dialogue suggests a general evasion from exploring issues of race.

The King of Queens operates on the use of simple humor and does so brilliantly. While this sitcom does not fall under the lines of “quality television”, it certainly meets its goal in producing laughter…good, quality laughter.

Pingback: DAD TV – Postfeminism and the Paternalization of US Television Drama Hannah Hamad / Massey University | Flow

Good day Mr. Kackman,

I am writing in reference to your book “Citizen SPY’ I am the grandson of Albert Taylor who you reference on page 205 at the bottom of the page. I am asking for your help. Where would I find the Memo to Maurice Unger, dated July 18, 1958. Regards to World of Giants ‘Teeth of the Watchdog’ scripts and annotations,” Box 206 UA/Ziv 7.2 SHSW. Where would this reference be located at. I have been researching Albert Taylor for family history. He was Orson Wells agent during War of the World, He was Associate Producer in Damn Yankees Broadway show, Ann Ronell and others. would you be able to help me with this matter.

Thank you for your time.

John Cunningham

soldiersailor1@gmial.com

J’aime votre article. Merci pour l’information. En tout cas, je vais revenir vous rendre visite très prochainement. Bonne journée

tuto référencement web http://agenceseolisniort.wordpress.com référencement internet définition