Hate, Dislike, Disgust, Distemper, and Distaste

One day at University of California, Berkeley, as I rushed into a 250-student lecture class, I was hailed by a student in the front row. Normally, I liked to wait until after the class for questions, but she looked so very concerned, so I asked what was up. Pen and paper in hand, ready and eager to take notes on my answer, she asked me, completely seriously, “Professor, why do you hate Celine Dion?”

Why do we hate or dislike what we hate or dislike? How do we explain it? And what does it mean?

Media and cultural studies have done a fine job of offering numerous explanations of why one might love Celine Dion, but we’ve hardly started to explore the meanings and workings of textual dislike, disgust, and distemper. Hence, if Random Person A sends flowers to a soap character or owns a Boba Fett outfit, my office bookcases are full of smart work ready to analyze what it means, but the bookcases are less capable if Random Person A sends hate mail to a program, campaigns for its end, or simply grabs the remote and changes the channel anytime it is on.

This is all the more bizarre because anti-fandom (by which I mean active dislike of a text, personality, or genre) is as common a response to any given media entity as is fandom. For all those who think Bono is Christ, there are those who think him the Anti-Christ; for all those who watch The OC eagerly, there are those proud of their avoidance of the show; and so on. Yet anti-fandom has not received its due attention as a viable viewing/consuming position. Indeed, if media effects and “couch potato” discourse is still so common, this is in part because we (the field, and society) seem much more keen to discuss people who turn on the media (and how, why, etc.), rather than those who turn it off (and how, why, etc.). Ron Lembo (2000) writes of our need to study “the turn to television,” but what of “the turn (away) from television.”

Learning from Fan Studies

As the study of the anti-fan’s apparent foil, fan studies might offer us the initial way forward. After all, it has taught us two key lessons that we might apply to textual hatred or dislike:

(1) fans can’t always be trusted to know fully why they like what they like (see, for instance, the superb psychology-meets-critical theory approach of Matt Hills (2002), Cornel Sandvoss (2005), and Lee Harrington and Denise Bielby (1996)); and

(2) fans experience a different text than do others: they read more of it, add texts and paratexts to the mix, and have a greater familiarity, hence changing the very shape and meaning of the text (see Henry Jenkins (1992), Will Brooker (2002), or the above).

So it would seem to be the case with anti-fans.

Anti-Fan Mantras

Texts exist on various levels: a rational-realistic level (do I believe this? does it make sense?), a moral level (do I approve of its morals?), a political level (how do I react to its politics?), and an aesthetic level (is it artful or beautiful?), to name some key ones. However, just as many of us tend to “defend” our favorite texts on levels that truthfully don’t mean much to us, so too do we tend to “damn” texts that we dislike for reasons not totally related to why we dislike them. The rational-realistic level is a particular unlucky bystander in both situations, as a viewer’s statements regarding a show’s “realism” or lack thereof quite often serve as little more than an indicator of fandom or anti-fandom on a deeper, more complex level (because, to a degree, any show can be called “realistic” or “unrealistic” and defended as such). So, if you hate the show, calling it unrealistic sounds reasonable, but may mean very little, just as if you love it, and call it realistic, this may mean very little.

Matt Hills (2002) also notes that fan cultures develop defensive “mantras,” used to explain why a show is good or not. These mantras may or may not accurately reflect a fan’s feelings, but they do the job of deflecting questions or ridicule. So too do anti-fans develop mantras. If we come armed with theoretically rich accounts of fan psychology and sociality, we are better equipped to see through such mantras, or to contextualize them. But it is time that, Bourdieu and others in hand, we attempt to more systematically understand anti-fandom and its own mantras.

Anti-Fan Textuality

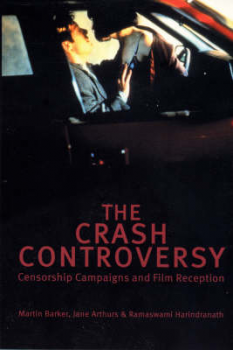

Some pioneering work here has been conducted by Martin Barker, Jane Arthurs, and Ramaswami Harindranath on their book The Crash Controversy (2001), which explores viewer reactions to David Cronenberg’s Crash. Barker et al. observe how most of the leaders of the drive to have the film removed from English cinemas had not actually watched the film. Thus, on the other end of the textual spectrum from fans, who often avidly consume huge portions of the text and its accompanying paratexts, are often anti-fans, who may only have read reviews, heard a friend’s one-sentence description (“a film about people who get turned on by car crashes”), or been told by a trusted opinion leader that it’s bad. In cases such as this, not having seen a text by no means precludes one from “decoding” it, even to the point of caring so deeply about one’s decoding that one will write letters to politicians or march in the streets about it.

Moreover, as Barker et al. also show, such anti-fan accounts can have such a strong impact on the text that they impose a set and limited frame through which all viewers will watch. In the case of Cronenberg’s Crash, public outrage over its “filthy” and “dangerous” messages made it hard for most of Barker et al.’s audiences to view “innocently” without such a frame (even if they actively rejected it). As I have written in previous columns, spoilers, previews, intro sequences, and the like all have remarkable powers to frame our viewings, and so too does anti-fan commentary.

Thus, by not looking at anti-fandom, we may have been missing many of the meanings, powers, effects, and intricate patterns of identification that audiences have been constructing. People can often define themselves just as strongly by what they dislike as by what they like; indeed, some viewers care much more about their televisual dislikes than likes. Hence the path to understanding how texts are situated in the daily lives of citizens and consumers would require spending considerable time in the land of anti-fandom, and we may have been missing a lot of what the media does and means by concentrating so intently on fans or casual viewers. (Which is not to criticize fan studies as much as it is to call for anti-fan studies).

Academic Anti-Fans

As an extension of anti-fan studies, we might come to better terms with our own pedagogical and research practice. After all, much of television studies’ output could be seen as an elaborate and sophisticated declaration of dislike. Whole books have been written on why such-and-such a program is bad, and whole careers have progressed because of long resumes full of examinations of the ills of television. Pedagogically too, many television studies academics see it as their sworn task to teach students away from the many nasties on television, and to open their eyes to all that is wrong with the box. Certainly, I too spend parts of my writing and teaching doing as much. Anti-fandom and academia are intimately connected, in other words.

But as I have been arguing, a proper study of anti-fandom would often reveal some deep-seated reasons for hate or dislike beyond what anti-fans themselves intuit. So let me ask provocatively, why don’t researchers/teachers who actively dislike a program state this outright, in the same spirit of honesty with which many fan researchers “confess” their fandom? Not only could this allow readers the chance to explore possible alternate reasons for the anti-fandom than the ones provided (though I suspect such devious readings take place confidentially with fellow colleagues/students), but it might also let us know the researcher’s/teacher’s relative distance from the text.

So why do I dislike Celine Dion? I usually say it’s because she perpetuates and sells a culture of junk romance that belittles women in the guise of “honoring” their feelings. But mantra aside, and truth be told, there are many singers who do this, so why dislike her in particular? A more honest answer would probably state that my anti-fandom works as a marker of national identity. Canadians always seem American to everyone else, or when they have remnants of a British private school in their accent, as do I, they sound like Brits to many Americans. But other than at hockey games, how often does one get to declare Canadianness? With Celine Dion, quite often, as she was (less so now, though) quite often in the news or on the radio. A violent reaction to and rejection of her allows a statement of Canadianness, since it usually begins, “Las Vegas can have her: she’s our gift to America” (emphasis added). Conveniently, too, by disavowing a famous Canadian, rather than proudly claiming her, I can craft a statement of seemingly non-nationalistic nationalism (often Canadians’ preferred form of nationalism). A proper psychologist might even dig further to find a Western Canadian’s aggression and resentment of French Canadian political power in there at some level. Thus, as bad as her music is, and as putrid as her lyrics are, Celine Dion is largely an image and an icon for me, one that a good ethnographer would hopefully coax out of me.

I bring up the specter of our own personal dislikes not to campaign for researchers to fill their work with apologia and self-psychoanalysis, but rather to point out that our practice is informed by more than just erstwhile academic research agendas. Some have questioned the degree of scholarship in fan-scholars, but so too could we play this game with questioning the degree of scholarship in anti-fan-scholar. We are all fans of some things, and we are all anti-fans of other things. As such, there is important work to be done in exploring the anti-fan side of media consumption. This work will illuminate our practice of research and pedagogy as a bonus, but the ultimate prize lies in filling in a vast area of the general map of media consumption.

Image Credits:

1. Kill the TV

Bibliography

Barker, Martin, Jane Arthurs, and Ramaswami Harindranath. The Crash Controversy. New York: Wallflower, 2001.

Brooker, Will. Using the Force. New York: Continuum, 2002.

Harrington, C. Lee, and Denise Bielby. Soap Fans. Philadelphia: Temple UP, 1996.

Hills, Matt. Fan Cultures. New York: Routledge, 2002.

Jenkins, Henry. Textual Poachers. New York: Routledge, 1992.

Lembo, Ron. Thinking Through Television. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2000.

Sandvoss, Cornel (2005) Fans, New York: Polity.

Please feel free to comment.

hierarchies of taste

This is an interesting take on taste and television. I think that television studies, as a discipline, needs to be particularly careful in the instance of researching taste given how often television is treated as “bad object” in discourses on taste and class and so on. For that reason, I’m particularly “down” on attempts to lionizing certain texts over others. For instance, things like “24” and “The Sopranos” are heralded for their narrative complexity, keen insight, etc. These accounts seem to use the very standards by which television is so often relegated to the cultural dustbin to claim these things.

taste/distaste and emotions

I’m with FH. It’s so frustrating to hear people say, “TV has gotten so much better,” when they are referring exclusively to programs that have crafted and marketed themselves as better-than-TV and more-like-art-cinema.

Anyway, Jonathan, thanks for your interesting essay. It seems to me that one way anti-fandom has been well examined is via studies of anti-TV activism, whether it’s liberal groups like Action for Children’s Television or right-wing groups like Focus on the Family (this obviously relates to the moral/political categories you mention). I suppose that this examination of activism is different from the issue of examining taste, per se. Yet taste (or rather distaste) is clearly at issue, even as right-wingers claim that what they object to is simply immoral content.

One thing that seems importantly bound up in taste and distaste is the issue of emotions. Sometimes, it can be much easier to teach a show I hate, find politically objectionable, etc. than to teach a show I love. It’s easier to make a rational argument about, say, the intensely masculinist impulses of Lost than to discuss the aesthetics of “The Body,” the Buffy episode in which Buffy discovers her mother’s dead body. This is one of the most tightly constructed (in both narrative and aesthetic terms) episodes of television I’ve ever seen, and it would seem like an ideal teaching text, but I simply cannot teach it because it makes me weep every time I watch it, and I don’t really want to do that in front of my students!

hate the game not the players!

Great article! It is also interesting to study how through focus groups and advance screenings, the industry is trying to target and reapproprite anti-fans in the process creating conflicts between the artistic and creative side and the marketing department. The whole process functions on co-opting as many fans as possible in order to keep the advertisers happy and the couch warm. The problem here is that these processes introduce cynicism from all sides, the fans, the artists, and the marketing department. No wonder many TV series and films get killed as soon as the earliest buzzes come back negative. Within this context, nurturing the art becomes the first thing to go. In today cutthroat climate, hit shows such as Seinfeld, which initially fared poorly in the ratings, would be thrown out in the trash! Let the haters hate!

parody as anti-fandom?

A provocative piece, Jonathan. I might suggest parody as an interesting case of anti-fandom, though I’m not quite thinking of affectionate, Mel Brooks-ian genre mash-ups. Rather, the venomous Trey Parker and Matt Stone provide examples of anti-fans that actively and consciously skirt issues of self-psychoanalysis in an attempt to reach the anti-fan in all of us (see recent “South Park” episodes “Cartoon Wars,” for example).

Likes and Dislikes

Great article. I think a big part of anti-fandom has to do with disownership as a form of self-identification. Just as rabid fans of an actor or singer will emulate a performer by putting up their poster on their bedroom wall, and in short doing everything they can to associate their own image with the image of their idol, anti-fandom functions on the same level by postioning oneself in opposition to ones own anti-idols in social discourse. I’d say true anti-fandom is defined not just be a distaste for a product, but an active, vocal aversion to the product or image in question. It’s sort of a “punk rock” social phenomenon in that way. In a consumer culture, the things we buy are just as important as the things we don’t buy. If we define ourselves by the products we consume, we equally define ourselves by the things we vehemently, and vocally, refuse to view/buy/consume.

Water Cooler Talk through the Magnifying Glass

Thank you for some more insight into how to critically study television. For my many analysis papers over the years, I have always chosen topics that I enjoy and can praise the creator’s work. I now wonder what it would be like to systematically break apart certain texts I do not like; in much the same way I would pick apart favourable texts. Your article has given me a springboard from which I can now approach analysis from a different perspective. I also would like to add that the average consumer should practice your techniques at the water cooler. Everyone is a critic and our friends are probably the most influential ones. Should we take their word for it or dig deeper into their hatred to better assess where they are coming from?

Define yourself: Personality vs. Dislikes

“People can often define themselves just as strongly by what they dislike as by what they like; indeed, some viewers care much more about their televisual dislikes than likes.” Of everything in the article, I feel that this sentence embodies all of Gray’s ideas. Personally, I am not one who cares more about my dislikes than my likes, but I do feel that dislikes do tell a lot about one’s personality. I love shows like Flavor of Love and America’s Next Top Model where on any given episode I can tune in and see something that reminds me of my self. As aspiring model and I hopeless romantic I can relate to the ideas and concepts of both shows. However, I loathe shows like Laguna Beach. I feel there is no substance behind the story line and I cannot relate to the characters on the show. With my personality, I could never in a million years sit and watch spoiled kids create their own dilemmas. My lack of empathy and patience will not allow me to have any appreciation for the show and others like it. Some may feel that these reasons are not valid enough to not watch a show, but at least I didn’t say it was unrealistic…

Pingback: Identity and Fandom « The Moritheil Review

Pingback: Dislike Dislike Dislike | AllGraphicsOnline.com

Pingback: Dislike Dislike | AllGraphicsOnline.com