“What we me worry?” What the new media literacy movement can learn from Mad Magazine and Wacky Packages

Aaron Delwiche / Trinity University

“What we me worry?” What the new media literacy movement can learn from Mad Magazine and Wacky Packages.

At one time, video-game researchers confronted an extraordinarily difficult climate within the academy. Like their predecessors who studied such “low-brow” topics as film, television, and radio, games scholars found themselves forced to defend the legitimacy of a controversial medium that was associated with prurient content and juvenile delinquency. Even today, academic treatises on video-games usually begin with a familiar lament about how this emerging medium “gets no respect.”

After many years of hard work, things are changing. This is an exciting time for researchers who specialize in the study of video-games and other forms of interactive media.

Though the threat of censorship continues to lurk on the periphery of American politics, there are signs that policymakers are starting to be more open-minded about the civic potential of video-games. Two years ago, Congress held hearings devoted to the regulation of offensive content on video-games. By April of this year, members of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce’s Subcommittee on Telecommunications and the Internet were open-minded enough to hold a hearing in the virtual world of Second Life.

Even in the midst of a recession, there is a significant amount of private and public financial support for games-related projects. Eighteen months ago, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation announced a $50 million initiative to fund research related to Digital Media & Learning. In April, the Federal Consortium of Virtual Worlds organized a conference bringing together government employees, educators, and the nascent virtual world industry. NASA, NOAA, the National Institute of Health, and the US Air Force are just a few of the American agencies that have announced substantial funding for innovative proposals related to virtual worlds and video-games.

In part, this changing climate can be credited to ground-breaking works such as Sherry Turkle’s Life on the Screen, James Paul Gee’s What Video Games Have to Teach Us about Learning and Literacy, and Steven Johnson’s Everything Bad Is Good for You. Aimed at general audiences, these books helped administrators, policymakers, educators, and activists realize that video-games have far reaching potential. Meanwhile, the Digital Games Research Association (DiGRA) and the Association of Internet Researchers (AoIR) – along with the annual State of Play and Games, Learning and Society conferences – have connected a far-flung global network of researchers and designers who share a mutual passion for video-games and virtual worlds.

In the face of these developments, games researchers may soon be able to set aside the claim that others are too critical of video-games. As we encounter greater cultural understanding of this medium, we should relax our defensive posture and voice our own criticisms of games without worrying about giving ammunition to would-be censors. In particular, we should turn our attention to the phenomenon of video-games that are consciously intended to alter to the real-life attitudes and behaviors of young gamers.

One way in which this can happen is by turning up the critical heat in the emerging conversation between games researchers, new media scholars, and media literacy activists. The new media literacy movement is an exciting development, but there are grounds for wondering if our field’s historic need to defend video-games is depleting some of the movement’s critical energy.

For example, consider the MacArthur Foundation’s first-rate report Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century.1 In this document, the authors argue that participatory media force us to reconsider many of the assumptions that underpinned the media literacy movement of the late 20th Century. Rejecting the tendency to perceive media messages as externally manipulated, the authors urge media literacy educators to prioritize the ways that audiences use digital tools to modify and redistribute media content.

This emphasis on the significance of participatory message production parallels the theoretical insights of Stuart Hall and other cultural studies theorists who argued that audiences approach media messages with a wide variety of negotiated readings. Though this shift is both logical and compelling, it carries some risks.

Just as some scholars have relied on negotiated readings as a rationale for avoiding discussions of manipulative and psychically intense content, there is a risk that “participatory media” will be deemed worthy of less critical scrutiny than traditional media.

It is dangerous to assume that the audience’s active participation in the construction of a media text is somehow less manipulative than one-way communication. In fact, communication researchers have long known that actively involving the audience is one of the most effective ways of changing their behavior.

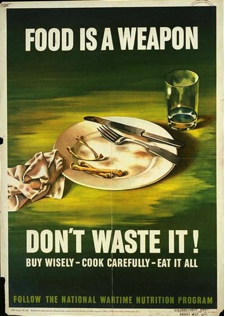

During World War II, propaganda scholars investigated two very different strategies for convincing female homemakers to consume organ meat. A series of studies compared the effectiveness of one-way lectures to interactive strategies that asked participants to talk with one another about the advantages of eating organ meat. The participation method was almost five times more successful than the traditional lecture format.2

Research on participation and self-persuasion reminds us that participatory media are not intrinsically liberating. Whether we are analyzing a television commercial, a print advertisement, a user-generated content contest on YouTube, or a massively multiplayer game, we still need to ask questions about the persuasive intent and structural motivations of the content’s primary creators.

For this reason, as media literacy educators develop a framework for understanding games and other interactive media, we can benefit deeply from the critical-minded perspective that is often embodied in Wacky Packages and Mad Magazine.

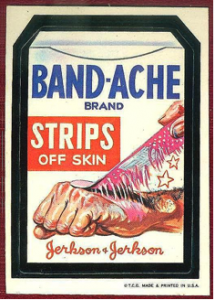

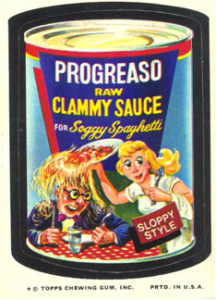

Originally produced by the Topps Company in 1967, Wacky Packages were trading card stickers that parodied leading consumer brands by melding gross-out humor with wry criticisms of consumer culture. These subversive trading cards were the brain-child of the noted comic artist Art Spiegelman who eventually received a Pulitzer Prize for his ground-breaking work Maus.

When I was nine years old, the Wacky Packages struck me as unbelievably hilarious. Appropriating the familiar Band-Aid logo, the Band-Ache Strips sticker matched graphic visuals to the slogan “Strips off Skin!” Putrid Cat Chow highlighted the nasty smell and disturbing canning practices of contemporary cat food, and Crakola Crayons promised “160 crumbled pieces” and “broken, bland colors made from Beeswax.”

Admittedly, the jokes in these trading cards were not the height of sophisticated humor. However, they effectively appealed to a nine-year-old sensibility while also communicating the fundamental insight that advertisers and large corporations do not have the best interests of consumers at heart.

The “usual gang of idiots” at Mad Magazine has performed a similar task for more than fifty years, combining gross-out humor with such consciousness-raising articles as:

• “The typical summer resort advertisement and the actual resort,”

• “The truth about secret ingredients,”

• “Behind the scenes at an ad agency,”

• “What to look forward to as a middle-aged mall rat,” and

• “What would happen to Disney characters in the real world?”

It is worth noting that Mad Magazine has continued to keep pace with cultural and technological changes over the years, and they were among the first publications to speak about video-games in a language that made sense to young people.

As we revamp the media literacy curriculum for the 21st century, Mad Magazine and Wacky Packages have something to teach us about the importance of humor, the value of simplicity, and — above all else — the importance of questioning the man behind the curtain.

Image Credits:

1. Aimed at a general audience, Gee’s What Video Games Have to Teach Us About Learning and Literacy has helped administrators, teachers, policymakers, and activists recognize the pro-social and educational potential of video-games.

2. America’s Army is an extraordinarily effective and well-designed persuasive video-game that encourages young people to consider enlisting in the army. Games theorists should ask themselves which they would prefer: internal critiques penned by researchers who understand the medium or external critiques authored by people who don’t really “like” games?

3. During World War II, propaganda researchers recognized that participatory, discussion-based messaging was the most effective way to transform consumer behavior. Heavy-handed lectures were much less successful.

4. The Wacky Packages trading stickers hinted that advertisers and manufacturers did not necessarily have the best interests of consumers at heart (“Band-Aches”).

5. The Wacky Packages trading stickers hinted that advertisers and manufacturers did not necessarily have the best interests of consumers at heart (“Clammy Sauce”).

6. Mad Magazine has kept pace with technological and cultural change for more than fifty years (No. 129, 1969).

7. Mad Magazine has kept pace with technological and cultural change for more than fifty years (No. 482, 2007).

Please feel free to comment.

- Jenkins, H., Purushotma, R., Clinton, K., Wiegel, M. and Robison, A. (2006). Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century. Chicago: MacArthur Foundation. [↩]

- Lewin, K. (1943). “Forces Behind Food Habits and Methods of Change,” in The Problem of Changing Food Habits: Bulletin of The National Research Council, 108 (October). Washington, DC: National Research Council and National Academy of Sciences, 35-65.; Wansink, B. (2002). “Changing Eating Habits on the Home Front: Lost Lessons From World War II Research,” Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 21(1) 90-101. [↩]

Thanks for the great column. I think it’s interesting that you cite humor as a likely tool for confronting the hidden intentions of interactive media production. For me, at least, humor seems very interactive – it requires that the sender and the receiver both agree on what is funny in order for a punch-line to work (completing the joke’s function). While this is a very different type of interactivity than you describe above, I wonder about the traits that both share. Right now I’m thinking about racist or misogynistic jokes that call for acceptance of unfair and slanderous stereotypes in order to be “funny.” Then again, I don’t think I would consider jokes of this type to alter behavior to the same extent that interactive media might. I am simply trying to find a clear example of humor that functions similarly to interactive media, at least in the way in which it can sometimes encourage a change in behavior or attitude.

Certainly, all of this seems like a rambling aside. I wonder, however, if humor is such a powerful tool precisely because of its interactivity. This would seem to reinforce the WWII studies you cite in your column; participation really is the key to getting people to do what you want. Furthermore, and more importantly, it also speaks to your column’s major concern, the behavior-shaping power of interactive media and the need to really examine the motives behind such enterprises. Funny how that works out.

Nice article.

Mad Magazine image credits have changed to http://www.madcoversite.com.

Just trying to fix a couple broken links.

Doug