Teen TV’s Post-Closet and Postracial Fictions

Wendy Peters / Nipissing University

On American television, homophobia and racism are increasingly characterized as “passé” and relegated to a bygone era. [1] On teen TV, high schools are often imagined in postracial and post-closet terms. And representations of racism and homophobia do the work of staging the moral enlightenment of the present.

I am interested in how these “post-” pretenses intertwine with neoliberalism on teen TV and give rise to post-closet narratives that serve to confirm whites as idealized gay subjects while symbolically disciplining or annihilating racialized gay and bisexual teens. Related to Melanie Kohnen’s column on Ugly Betty, [2] post-closet and postracial narratives minimize homophobia and reassert racial hierarchy, while each is denied. In this column, my focus is on representations of post-closet high school students in the 2010-2011 season of teen TV.

The 2010-2011 season of scripted Canadian and American teen TV featured more non-straight teen characters in one year than each previous decade. Given the concurrent media focus on LGBT youth and homophobic bullying in schools, I selected series set in high schools. As Ron Becker explains, post-closet characters are introduced to viewers as already “out” and never struggle with their sexuality. They tend to be white, affluent, male, avid consumers, apolitical and likeable. Their sexuality is presented as innate, stable, permanent, desexualized and chaste, or more recently, monogamously committed. [3] These characteristics are in line with the values of neoliberalism, including self-reliance, affluence, consumption, privatization and the family as the site of social reproduction. [4] By showing certain privileged and privatized gay men—and to a lesser extent lesbians—television made room for gay characters who conform to what Lisa Duggan calls “the new homonormativity… a politics that does not contest dominant heteronormative assumptions and institutions but upholds and sustains them, while promising the possibility of… a privatized, depoliticized gay culture anchored in domesticity and consumption.” [5]

The examples I show illustrate how race, class, sex, sexuality and privatization figure in the depictions of Blaine on Glee, Griffin on The Secret Life of the American Teenager, Ian on 90210, Maya and Samara on Pretty Little Liars, and Zane on Degrassi. These post-closet teen characters are depicted as likeable, confident, out, proud, fashionable, affluent and popular with their high school peers. They are much like their “good” straight peers who desire long-term monogamous relationships. Of the six characters depicted as post-closet in 2010-2011, three read as white and middle-class while identifying as gay and male (Blaine on Glee; Griffin on The Secret Life of the American Teenager; Ian on 90210). Additionally, there is one white, affluent, lesbian (Samara on Pretty Little Liars). The remaining two post-closet characters read as mixed-race and middle-class, one gay-identified male (Zane on Degrassi) and a bisexual / queer female (Maya on Pretty Little Liars). [6] That both of the racialized characters are fair-skinned conforms to the ongoing televisual erasure of darker bodies, a representation Amy Hasinoff describes as where “marketable lighter-skinned mixed-race [characters] can be positioned to stand in for all racial differences.” [7]

In the 2010-2011 season of teen TV, all four of the white post-closet teens are safe, secure, well-integrated into their schools and do not face homophobia. [8] Blaine on Glee, Samara on Pretty Little Liars and Ian on 90210 all attend schools that are explicitly wealthy and opposed to homophobia, while Griffin on Secret Life attends a middle-class public high school that is implicitly post-homophobia. The privatization of gay-positive schools offers a tacitly neoliberal acknowledgement of homophobia when Blaine is shown attending a lavish, all-boys private school with a zero-tolerance policy on homophobic bullying, while Samara’s private prep school has an LGBT Pride Club. Glee and Pretty Little Liars explicitly link privatization with safety for gay and lesbian students when Blaine and Samara are shown mentoring their counterparts who are struggling to come out in public schools. Such narratives present homophobia as a metric to evaluate schools and implicitly frame public schools as lacking. Well-adjusted and physically secure post-closet teens are articulated to whiteness, affluence and—in some instances—privatization.

The narratives of the two racialized teens are distinct from the white post-closet characters and unique in relation to each other. Race is not mentioned in relation to post-closet characters in 2010-2011, and the avoidance of race is nearly acrobatic at times. In a Pretty Little Liars episode, tellingly titled “The New Normal,” a parent complains that Emily, who is racialized and “out,” is given preferential treatment on the swim team over his white and (presumed-to-be) heterosexual daughter. A teacher explains: “He came in making a big deal about how he thinks Emily’s getting special treatment because she’s gay.” [9] Race is entirely overlooked and in keeping with “post-” discourses there is a suggestion, though narratively discredited, that a privileged student is the victim of so-called “reverse discrimination.” It is within this kind of postracial context that the violence faced by Zane is characterized as exclusively homophobic in nature, while the violence faced by Maya is individualized and narratively divorced from racism and homophobia.

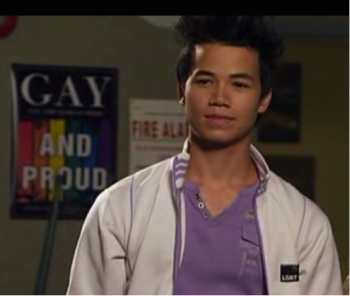

Degrassi’s Zane conforms closely to Becker’s description of post-closet gay characters. His narrative diverges from the white teens when he is bullied by other “jocks” in his Canadian public high school and in response he promotes and attends a community roundtable addressing homophobia in schools. [11] Zane is a rare post-closet character who is shown facing and resisting homophobia, particularly through a public, community-based, activist solution. He is an atypical post-closet character insofar as he is racialized, in a high school that is not exclusively anti- / post-homophobia, and in contact with a politicized queer community. When taken together with the white, post-closet characters, it is notable that Zane’s divergence from more common representations of whiteness and privatization leave him symbolically vulnerable to homophobic violence and harassment in his ostensibly postracial high school context.

Maya on Pretty Little Liars (PLL) is a lone and extreme outlier in relation to post-closet characters and homonormativity. She is racialized, female and known to have sexual relationships with male and female characters. Her transgressions are underscored as dangerous when she is stalked and murdered at the end of the first season. Her killer is later revealed to be a young black man with whom she was romantically involved when her parents sent her to rehab for smoking pot and skipping school. Maya’s vulnerability and death are not narratively linked to homophobia or racism, but rather individualized as consequences of her unfixed and active (racialized) sexuality, opposition to valued institutions such as family, school and the law, as well as the jealousy of a violent and homicidal black man. It is striking that the teen who falls furthest outside the valued characteristics of post-closet TV and homonormativity is symbolically punished with a horrific death.

One might argue that the relative safety of white teens and the violence faced by racialized youth is a realistic aspect of these storylines or that teen TV draws attention to under-resourced public schools lacking supports for queer students. Yet, these narratives primarily elide the existence of racism, homophobia and normative privilege, despite their tacit acknowledgement. Together, these post-closet narratives favour white gay teens—especially those whose families can afford to privatize their schooling—while endangering lighter-skinned racialized queer youth. Further, darker-skinned racialized post-closet characters are precluded from representation entirely, while tropes of the violent black man round out this “postracial” hierarchy. The dangers of “post-” politics are dramatized implicitly in these series as post-closet teens often serve to highlight the lack of homophobia in fictional high schools, while postracial discourse enables the continued privileging of white gay subjects alongside the penalizing and vilification of racialized teens. Narratives denying the existence of such discourses are bound to repeat them.

Image Credits:

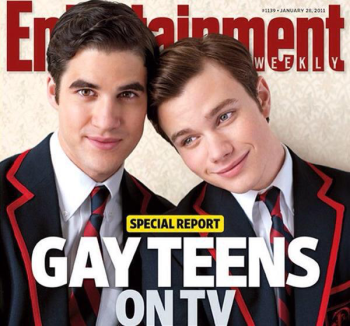

1. Blaine and Kurt in Glee

2. Brothers and Sisters

3. The New Normal

4. The Fosters

5. Modern Family

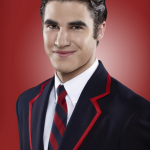

6. Blaine on Glee

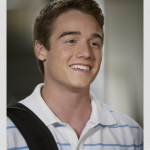

7. Griffin on The Secret Life of the American Teenager

8. Ian on 90210

9. Samara on Pretty Little Liars

10. Blaine’s private school is visually characterized by an all-male and racially diverse cast in formal uniforms surrounded by heavy drapery, wood paneling and oil paintings.

11. Zane on Degrassi

12. Maya on Pretty Little Liars

13. Zane speaks at the community roundtable about homophobia in schools. (author’s screen grab)

14. Maya at the time of her death

15. Lyndon, Maya’s killer, attempts to kill again, but is slain in self-defense by one of the PLL protagonists.

Please feel free to comment.

- Becker, Ron. “Guy Love: A Queer Straight Masculinity for a Post-Closet Era?” Queer TV: Theories, Histories, Politics. Eds. Glynn Davis and Gary Needham. New York: Routledge, 2009. 127; Ono, Kent A. “Postracism: A Theory of the ‘Post’- as Political Strategy.” Journal of Communication Inquiry 34.3 (2010): 228. [↩]

- Kohnen, Melanie. “Tying Narrative Threads by Opening Closet Doors: Coming Out on Ugly Betty.” Flow 12.05 (July 2010). [↩]

- Becker, Ron. “Post-Closet Television.” Flow 7.03 (November 2007); Becker, “Guy Love,” 121-40. [↩]

- Cossman, Brenda. “Sexing Citizenship, Privatizing Sex.” Citizenship Studies 6.4 (2002): 484. [↩]

- Duggan, Lisa. The Twilight of Equality? Neoliberalism, Cultural Politics, and the Attack on Democracy. Boston: Beacon Press, 2003. 50. [↩]

- I write that these characters “read as” white or mixed race because my claim is not that they “are” white, for example, but that they are presented and likely read as white. I offer these categorizations to reflect the shorthand that is often employed in “racial sightlines” (Guterl, Matthew Pratt. Seeing Race in Modern America. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2013). I also want to clarify that Kurt Hummel, a white, gay-identified teen character on Glee is depicted in 2010-2011 as out, but I apply Becker’s definition of “post-closet” to exclude all teen characters who are shown to struggle with coming out onscreen. [↩]

- Hasinoff, Amy Adele. “Fashioning Race for the Free Market on America’s Next Top Model.” Critical Studies in Media Communication 25.3 (2008): 330. [↩]

- A notable exception is that 90210 utilizes the trope of the closeted bully. In that narrative, Ian is called a “faggot” and is physically attacked by a closeted character. Importantly, the series neoliberally individualizes homophobia at West Beverly Hills High School to the mind and actions of one closeted character. [↩]

- S01 E17. To clarify, Emily is “out,” but does not meet the criteria for a post-closet character as she is shown to “come out” as part of her narrative (see footnote 6). [↩]

- Actor Bianca Lawson (right) has been playing a teen on teen TV for over 20 years, including Buffy, Dawson’s Creek, Secret Life, Pretty Little Liars and more. [↩]

- S10 E19 [↩]