The Untold Story of the Original, Factory-Produced, Horror/Exploitation VHS Collector David Church / Indiana University

The nostalgic revival of VHS, a supposedly “dead” video format, has recently reached critical mass, as seen in the proliferation of zines, collectors’ guides, and fan conventions for rare tape hounds; the re-purposing of VHS tapes within the art world; the remixing of ephemeral VHS footage by websites like Everything is Terrible! and TV Carnage; the screening of campy VHS texts at repertory theaters; the new release of limited VHS editions by small horror/exploitation video labels like Gorgon Video, Intervision, and Massacre Video; and a rash of documentaries on VHS culture.1 Among the latter, Adjust Your Tracking: The Untold Story of the VHS Collector (2013) best crystallizes the solipsistic logic of VHS collecting in general. Jointly produced by and for collectors, the film features VHS aficionados ruminating about their personal video libraries, providing a representative glimpse into what is arguably an ethos of bad faith lurking beneath this esoterically residual commodity fetish.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vvGNfx0TaE4[/youtube]

Whether exploring dusty VHS boxes in failing video stores or bidding against each other on eBay, VHS collectors most closely resemble the hipster collectors of vintage vinyl records in their attention to “authentic” materiality, with the oldest or most obscure editions of an album/film accruing the most subcultural value. However, the main difference is vinyl’s audiovisual superiority to the digital formats (CD, MP3, etc.) that succeeded it—one of the major reasons that vinyl collectors prefigured its comeback as a viable format released by even the major record labels. VHS, by comparison, cannot claim such audiovisual superiority over DVD or Blu-ray; instead, VHS collectors reframe the analog format’s low-definition deficits as a haptically appealing and nostalgically sympathetic underdog. In this regard, VHS nostalgia bears a closer resemblance to the recent nostalgia for magnetic cassette tapes within indie/lo-fi music cultures,2 with the “rougher” sound of low-tech analog noise seemingly distanced from digital audio’s more “feminine” connotations of slick-and-easy mainstream accessibility.

Several scholars have discussed these aesthetic preferences in relation to bootleg videotapes,3 but VHS collectors (largely late-20s to early-40s males) champion the format in general because it reminds them of their youths spent watching films on the similarly “underdeveloped” technology. Since these collectors likely watched all manner of films on VHS during those years, nostalgia for VHS as a format-specific aesthetic is thus far more reflective of longings for one’s own youth than for the texts that once thrived on such formats. Moreover, if the rise of digital video formats fueled VHS’s obsolescence, then the current wave of nostalgia for VHS is paradoxically fueled by the market penetration of DVD and Blu-ray, rather than opposed to it. This nostalgia, then, is symptomatic of not only video stores’ disappearance as brick-and-mortar places once built upon VHS, but also the impending disappearance of physical video formats altogether as streaming media supplant the material objects long acquired by collectors.

Yet, as much as digital formats are construed as the enemy of VHS, this collector culture would not exist without the liquidation of video store stock. Although collectors may condemn corporate behemoths like Blockbuster Video for bankrupting independent mom-and-pop stores, the latter were more likely stocked with exploitation films distributed by minor video labels in the years before the Hollywood studios embraced VHS distribution. If the small stores favored “breadth-of-copy” over Blockbuster’s “depth-of-copy” of big Hollywood releases,4 then the liquidation of independent stores has actually fueled collectors’ ability to inexpensively scavenge old tapes that were not originally priced to own. Beneath the posture of hipster disaffection, then, the very existence of a VHS collecting subculture is as indebted to the industrial effects of mainstream corporations like Blockbuster as opposed to them.

VHS collectors specifically resemble a hipster subset among fans of culturally denigrated genres, privileging low-budget horror and exploitation films while largely neglecting more reputable genres (regardless of how rare tapes from other genres may be). By focusing on genres already associated with cultural detritus, they conflate VHS and horror/exploitation films as similarly “trashy,” thus undercutting their own claims to VHS’s cultural value.5 This bad-faith embrace of the outmoded and déclassé is ultimately rooted less in sincere genre appreciation6 than in paracinematic reading strategies which ironically privilege the aesthetically “worst” films as esoteric great works—albeit beneath a veneer of nostalgia focused less upon the films themselves than upon collectors’ youthful experiences with VHS as a format in general.7 Small wonder, then, that <em<Adjust Your Tracking’s interviewees note their difficulty explaining to others why they would spend so much time and money collecting enjoyably “bad” films on an audiovisually inferior format. Yet, were their hobby easy to explain, it would cease to seem as “rebelliously” misunderstood as VHS itself might today seem to the non-hip. Moreover, if appeals to childhood nostalgia cannot wholly justify such affective investments, collectors can always fall back on the exchange value of rare tapes as justification for their investments.8 Consequently, the subcultural allure of VHS collecting depends on the very contradictions involved in attempting to revalue an obsolete-cum-inferior format.

Indeed, despite this subculture’s gravitation toward particular genres, their discourses typically subsume the filmic text to the tape’s original packaging, with certain types of 1980-era containers and cover art garnering special repute. Wizard Video’s covers, for example, are prized among collectors as most exciting and lurid, often in contradistinction to the quality of the advertised films themselves. This disjuncture between paratextual promises and actual filmic texts is, of course, a historical strategy of exploitation film publicity in general, not a trait unique to VHS in any way—but the youthfully imaginative reveries spawned by such packaging becomes part of VHS’s nostalgic thrill. In 2013, for example, Wizard Video head Charles Band announced that he had discovered a cache of unused “big boxes” in a warehouse, and would sell these pristine original boxes for $40 each, accompanied by a non-vintage duplicate cassette of the film in question—a notable subordination of remediated text to vintage paratext. Yet, VHSCollector.com soon raised doubts about the authenticity of these boxes, accusing Band of merely printing reproductions to cash in on the VHS collecting trend.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wC6Dc1QMK1w[/youtube]

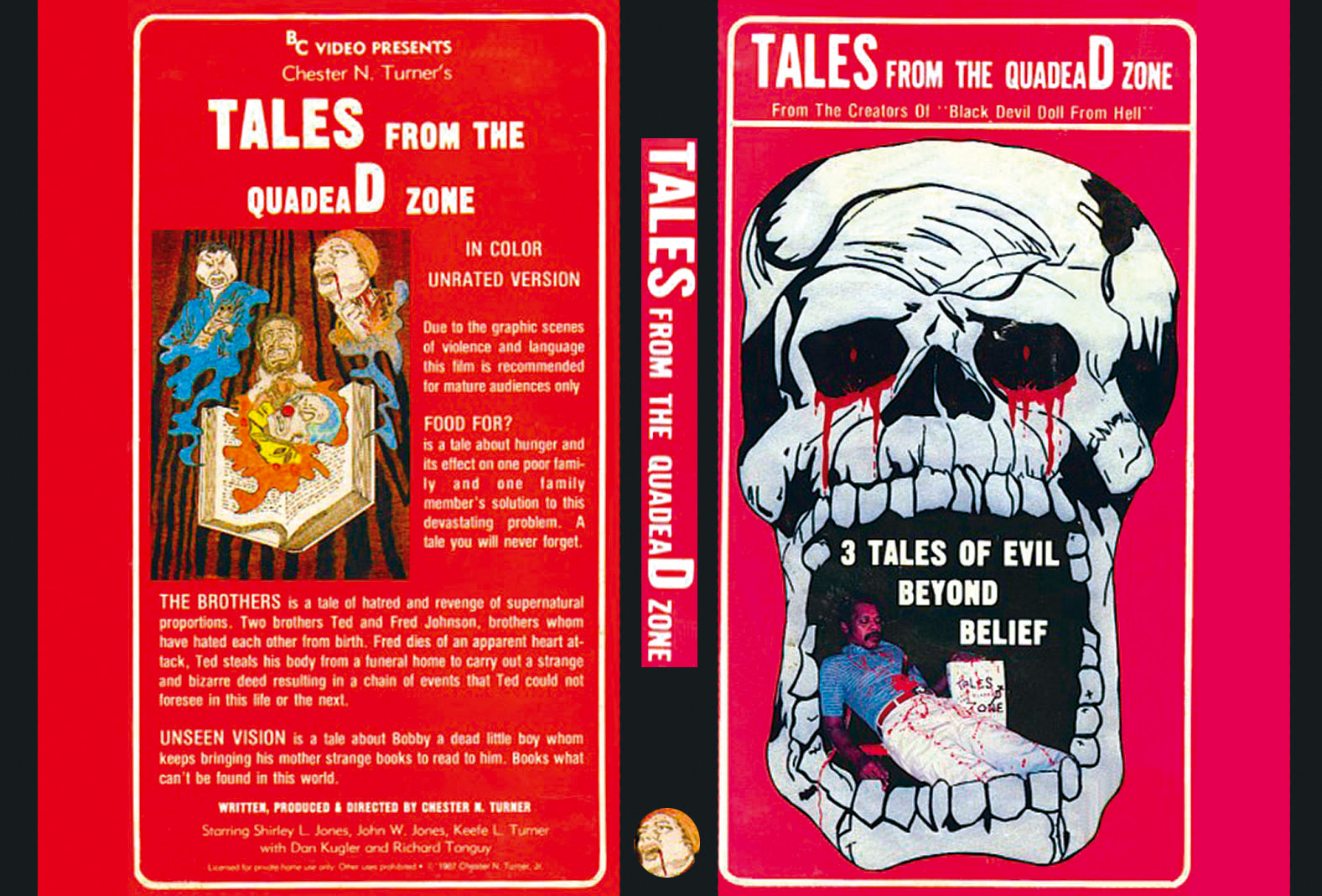

Another case in point is VHS collectors’ holy grail, Tales from the Quadead Zone (1987), a shot-on-video horror film whose original copies sell for over $700 on eBay; if this text seems “worthless” by normative aesthetic standards, then its rarity as a material object can accrue all the more subcultural value as “exclusive” to a dedicated few. In 2013, Massacre Video reissued Quadead on DVD and VHS—the latter edition limited to 150 copies—along with limited-edition hardboxes modeled after the original VHS packaging. Scarcity may thus be manufactured for these replicas, but reproductions still bear far less subcultural value than the original object, much as brand-new vinyl reissues may allow readier access to certain albums on a residual format but are not as sought-after by collectors.

VHS box cover for original BC Video release of Tales from the Quadead Zone (1987)

VHS collectors represent a last gasp of the old-school paracinema subculture once largely associated with bootleg video circulation, but since threatened with its own obsolescence. Yet, unlike an older generation of bootleg traders, today’s VHS collectors place far less value upon access to once-rare texts themselves than upon the factory-produced original cassettes/boxes as material objects, because many of the texts that once circulated through bootlegs have since been either digitized for distribution on cult-film torrent websites or remediated as official DVD releases. Despite collectors’ rhetoric about “rescuing” texts that have only been released on VHS, digital rips of such obscure texts are not difficult for fans to find online—hence the defensive shift toward subculturally valuing factory-produced original editions instead of duplicate versions. Moreover, despite their preservationist rhetoric, these collectors do not actually “archive” these tapes so much as lock them away within their private homes, since actual archiving would involve granting a degree of public access antithetical to the rare object’s subcultural value. With textual access now subsumed by paratextual preciousness, the VHS collector disingenuously privileges the exclusivity of vintage-ness while not actually challenging the mainstream aesthetic standards that denigrate the low-budget text’s apparent “badness” in the first place.

Image Credits:

1. VHS convention (Adjust Your Tracking DVD)

2. Image dropout (Adjust Your Tracking DVD)

3. Quadead Zone VHS cover

4. A VHS collector’s library (Adjust Your Tracking DVD)

Please feel free to comment.

—————

- See Iain Robert Smith, “Collecting the Trash: The Cult of the Ephemeral Clip from VHS to YouTube,” Flow 14, no. 8 (2011): http://flowjournal.org/2011/09/collecting-the-trash/; Jeff Scheible, “Video After Video Stores,” Canadian Journal of Film Studies 23, no. 1 (2014): 59-68; and Daniel Herbert, “Nostalgia Merchants: VHS Distributors in the Era of Intangible Media” (paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Cinema and Media Studies, Seattle, WA, March 19-23, 2014). These documentaries include Video Nasties: Moral Panic, Censorship, and Videotape (2010),Adjust Your Tracking (2013), Rewind This! (2013), Plastic Tapes Rewound: The Story of the ‘80s Home Video Boom (2014), VHS Forever? Psychotronic People (2014), and VHS Massacre (2015). [↩]

- Paul Hegarty, “The Hallucinatory Life of Tape,” Culture Machine 9 (2007): http://www.culturemachine.net/index.php/cm/article/viewArticle/82/67; and Marc Hogan, “This Is Not a Mixtape,” Pitchfork, February 22, 2010, http://pitchfork.com/features/articles/7764-this-is-not-a-mixtape/. [↩]

- Joan Hawkins, Cutting Edge: Art-Horror and the Horrific Avant-Garde (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000, chp. 2; Kim Bjarkman, “To Have and To Hold: The Video Collector’s Relationship to an Ethereal Medium,” Television and New Media 5, no. 3 (2004): 217-46; and Lucas Hilderbrand, Inherent Vice: Bootleg Histories of Videotape and Copyright (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009), chp. 4. [↩]

- Frederick Wasser, Veni, Vidi, Video: The Hollywood Empire and the VCR(Austin: University of Texas Press, 2001), 146-51. [↩]

- Herbert, “Nostalgia Merchants.” [↩]

- See David Church, Grindhouse Nostalgia: Memory, Home Video, and Exploitation Film Fandom (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015). [↩]

- On bad faith in cult cinema, see Jeffrey Sconce, “‘Trashing’ the Academy: Taste, Excess, and an Emerging Politics of Cinematic Style,” Screen 36, no. 4 (1995): 371-93; and David Andrews, Soft in the Middle: The Contemporary Softcore Feature in Its Contexts (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2006), chp. 8. In an understandably partisan article by an Adjust Your Tracking interviewee, Katie Rife of Everything is Terrible! divides VHS collectors into “two broadly defined camps: the nostalgists, who are looking to relive childhood memories, and the aesthetes, who are drawn to the roughhewn beauty of low-budget horror” (Rife, “Direct from Video: The Rise of the VHS Collector,” The A.V. Club, October 27, 2014, http://www.avclub.com/article/direct-video-rise-vhs-collector-210631)—but I would argue that such distinctions collapse in actual practice, with nostalgia serving as both an affective defense of audiovisual inferiority and a means of (mis)directing subcultural value toward low-budget genres instead of just any movie that once appeared on VHS. [↩]

- Kate Egan, Trash or Treasure? Censorship and the Changing Meanings of the Video Nasties (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007), 170. [↩]