Reflections on Actors III: The Work of the Dubbing Actor – Performing Gollum in the German version of Lord of the Rings

Simone Knox / University of Reading

As I have argued in co-authored work elsewhere, the audio-visual translation practice of dubbing, where the audio track of an exported film or programme is replaced with one in the language of the target market, continues to be marginalised and reductively understood in a range of debates.1 This is despite the unquestionable importance of dubbing to cinema and television in a range of countries, and despite a resurgent interest in matters of globalisation within film and television studies. Continuing with my interest in the lived experience of contemporary screen culture, I will now pay attention to dubbing actors: performing labour that is by its nature literally invisible and at the same time raises issues of transparency, the work of the dubbing actor needs to be understood beyond dogged fixations on dubbing’s supposed lack of originality, and authenticity, as well as the constraining matters of practicality, such as the need for lip-synchronisation.

I will hinge my discussion around the work of one particular dubbing actor as it features in the German version of Lord of the Rings. The dubbing of this film franchise, and Gollum’s voice especially, received positive attention within fan, industry and press discourses in Germany. The dubbing scripting and direction as well as the vocal performance of Gollum were all undertaken by Andreas Fröhlich, a voice artist whose long career spans different forms and genres. My discussion will combine my own close analysis with a recent original interview conducted with Fröhlich, in order to engage with the insider knowledge of a practitioner in a sector of the creative industries that has been without a voice in scholarly debates for far too long.

Of course, focusing on the dubbing of this fictional character is an interesting choice, given that he is originally a hobbit known as Sméagol who, corrupted by the Ring, becomes Gollum, named after his habit of making, as Tolkien himself put it, a ‘horrible swallowing noise in his throat’.2 Thus, vocal performance is inscribed into the character from its very genesis. And indeed, for Peter Jackson’s big screen adaptation, Andy Serkis – who was initially offered short-term employment to provide the voice-over for Gollum but went on to gain international prominence for his motion capture work for this digital character – has spoken of the importance of the voice for the part:

For me, it is where his pain is trapped. That emotional memory is trapped in that part of his body, his throat. In just doing the voice, I immediately got into the physicality of Gollum, and embodied the part as I would if I were playing it for real.3

Given the centrality of the voice to the role, and Fröhlich’s extensive professional experience, it comes as a surprise that Fröhlich’s casting was marked by a degree of chance rather than the result of an extensive search for the right vocal performer. Hired to take charge of the dubbing script and direction for the first film in the trilogy, Fröhlich did not originally expect to take on the German voice for Gollum. However, he stepped in when the part – rather minor at this stage – had not been cast in the run up to the film’s release in Germany due to a studio oversight. In terms of his approach to the role, he notes the importance of Serkis’ work in bringing the character to life, and tells how:

I basically oriented myself on what Andy Serkis was doing, and instantly ruined my vocal chords. I didn’t know how to do this. I wasn’t breathing correctly, I started off too high […].4

Interestingly, the practitioner’s perspective here bears out that dubbing is not, or perhaps rather should not be, so concerned with imitation – indeed, imitation can even play havoc with the very instrument needed for dubbing, the performer’s voice. This usefully complicates scholarly views such as Hassanpour‘s that dubbing should be understood ‘as an activity involving a recreation of the original text.’5

With Gollum’s part from the second film onwards substantially bigger, Andreas Fröhlich knew he had to change his approach, and making use of the time available, set out to find the voice for Gollum. His search saw him pacing through his Berlin flat, ‘muttering and giggling and looking for this special voice.’ He says that he struggled until the moment when:

I went to bed and my wife was lying beside me and I couldn’t sleep. I was muttering and doing these strange voices […]. […] Then I turned my face to her, and then I started whispering ‘my precious’ into her ear. She was laughing, and then I found this voice, lying in bed with my wife, because I started talking to her like Sméagol was talking to Gollum. I realised that when I have a person to talk to, that I found this voice. […] You have a relationship to your wife, and like I have a relationship to her, Gollum has a relationship to Sméagol.

What his fascinating account here shows is that, while Serkis’ performance was, of course, an important point of reference for Fröhlich, it was when the latter was not in proximity to Serkis’ work that he made progress. It was only when Fröhlich realised the importance of Gollum as a relational creature, in a moment of direct embodied experience for himself, that he could begin to find the voice. With Serkis’ performance a point of reference but not an object for mere imitation, Fröhlich’s dubbing performance drew on a range of input, including his own critical reflection of Serkis’ work, physical techniques, emotional experiences and technical skills, to find his own voice for Gollum.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rjPDAe_kTls[/youtube]

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pbuUQIbAkac[/youtube]

The voice for Gollum that Fröhlich ultimately developed can be experienced, and will be compared by me to Serkis’, via the provided clips, which show the same scene from The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (2002) and Der Herr der Ringe: Die zwei Türme (2002). This is an interesting scene in terms of performance, given that the film here explicitly foregrounds the split personality of Gollum/Sméagol, with the two personas arguing over their loyalty to Frodo.

Serkis has spoken of his decision to develop a choking sound for Gollum’s voice based on the character’s guilt over strangling his brother, and further inspired by Serkis witnessing his cat retch up a fur ball.7 Certainly, his is a guttural vocal performance, for which, I would argue, he lowers the centre where his voice is produced and makes use of phlegm in the back of his throat as a resonator to produce a rumbling sound. This underlying growl, combined with the physical strength evident in the jumps the character makes, invest his Gollum with a sense of malevolent threat. While the sibilant ‘s’ in Gollum’s speech inevitably connects that character to the snake, there is a quality of a lurking, ape-like monster to Gollum with Serkis (who, interestingly, went on to undertake motion capture for primate characters twice).

Fröhlich, on the other hand, to me produces his voice more through lips and tongue, and with his pitch located more mid-register, his Gollum has a drier, more hissing delivery. In congruence with the prevalence of sharp sounds (such as ‘s’, ‘ch’ and ‘sch’) in German, Fröhlich’s voice connects to and reorients Gollum’s coiled hunch to shift the character more emphatically towards connotations of the snake. His Gollum is certainly a relational creature; developed here, I would suggest, to a point of being a more devious, if not sadistic, character – note the pronouncedly gleeful modulation of Fröhlich’s tone when Gollum tells Sméagol that nobody likes him. These nuances of performance shift the dramatic construction in subtle and interesting ways.

Much, much more remains to be said about the performances here, including those of Sméagol. But in need to conclude, I will note that the work of a highly skilled voice artist such as Andreas Fröhlich shows that dubbing needs to be understood not simply as a recreation, but as a re-creation of the source text. Paying more attention to dubbing as a creative act of performance stands to make an enriching contribution to scholarly (and other) debates about performance and screen culture. Here, the perspective of the creative personnel involved is a fecund resource that can yield intriguing insights and generate new knowledge.

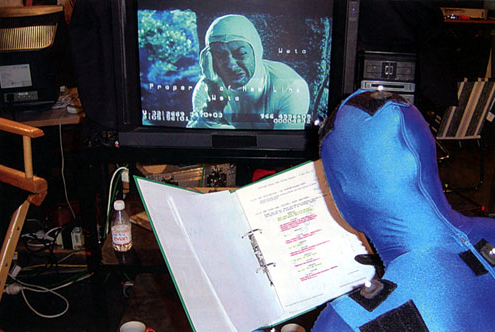

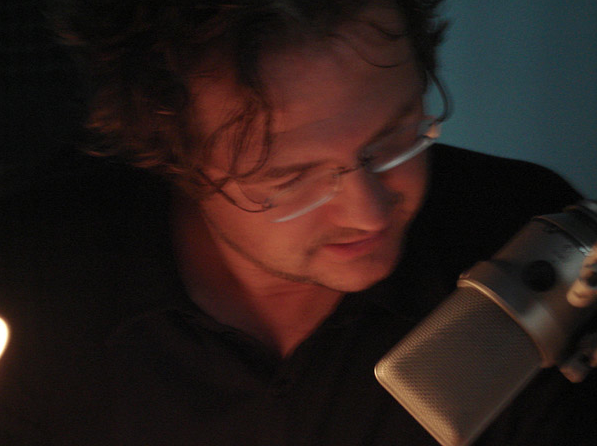

Image Credits:

1. Serkis–Gollum–Fröhlich

2. Andy Serkis Motion Capture

3. Andreas Fröhlich

Please feel free to comment.

- See Simone Knox and Christina Adamou, ‘Transforming Television Drama through Dubbing and Subtitling: Sex and the Cities’ in Critical Studies in Television 6: 1 (2011), pp.1-21. [↩]

- J. R. R. Tolkien. The Hobbit, or There and Back Again. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1937, p.120. [↩]

- Andy Serkis, http://www.serkis.com/lord-of-the-rings-movie.htm. For a discussion of Serkis’ motion capture work – he prefers the term performance capture – and the critical issues it raises for scholarship, see Tanine Allison, ‘More than a Man in a Monkey Suit: Andy Serkis, Motion Capture, and Digital Realism’ in Quarterly Review of Film and Video 28: 4 (2011), pp.325-341; Sean Cubitt and Barry King, ‘Dossier: acting, on-set practices, software, and synthespians’ in Harriet Margolis et al. (eds). Studying the event film: The Lord of the Rings. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2008, pp.111-125; and Tom Gunning, ‘Gollum and Golem: Special Effects and the Technology of Artificial Bodies’ in Ernest Mathijs and Murray Pomerance (eds). From Hobbits to Hollywood: Essays on Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings. Amsterdam; New York: Rodopi, 2006, pp.319-349. [↩]

- All quotations from Andreas Fröhlich are taken from my personal interview with him (17 June 2014), except where otherwise indicated. [↩]

- Amir Hassanpour, ‘Dubbing’ in The Encyclopedia of Television, http://www.museum.tv/eotv/dubbing.htm; emphasis added. [↩]

- Andreas Fröhlich quoted in http://www.taz.de/1/archiv/digitaz/artikel/?ressort=ku&dig=2010%2F06%2F12%2Fa0018. My translation. [↩]

- See Andy Serkis. Gollum: How We Made Movie Magic. London: Collins, 2003. [↩]

I agree with your conclusion that “dubbing needs to be understood not simply as a recreation, but as a re-creation of the source text.” But I wonder how one can argue whether a dub (from English to foreign or vice-versa) can be regarded as a different style but faithful to the source material versus a poor dubbing performance. Especially in the realm of anime fandom, voice actors are criticized for changing the entire persona of a character merely by a difference in pitch. Do you feel that this is an area of mere subjective criticism or an issue that actors need to consider when choosing how to interpret their characters?

Hi Lyz,

thanks for your comment and your interesting question. My answer to this would be this: Dubbing (or certainly good dubbing) revolves around a creative practitioner being able to make a set of choices and decisions, based on their professional experience, training and skills, their creative perspective and reading, as well as artistic hunch as to what kind of vocal performance will work for their character, for the particular project in question (which is, of course, likely to involve collaborators). For this, the dubbing artist will take account of the source material they are dealing with, but be working to overcome getting constrained by issues of fidelity and/or imitation (as Andreas Fröhlich managed to do).

My view is that a dubbing actor, similar to any other actor, will not be taking account of fan (or other) responses; and rightly so. I say ‘and rightly so’, because, for any creative practitioner, anticipating responses to their work is not a successful objective for the long term (as well as most likely impossible) – my hunch is that the very best dubbing actors are likely to be more concerned with finding the psychological realism for and emotional truth of their character (whether they are explicitly drawing on Stanislavskian actor training or not).