Film-makers, Hell-raisers, Test-takers: The Public Shaming of Modern Renaissance Men

Sean L. Malin / University of Texas, Austin

When the actor, celebrity, and general artiste Zach Braff announced in the spring of 2013 that he was soliciting funds for his second feature from crowdsourcing website Kickstarter, the Internet and everyone on it exploded with righteous fury. Braff had starred in the (syndicated) primetime television series Scrubs for years, as well as several major films, and was thought to be asking for money where he should simply have ponied up his own. He was also the writer, director, producer, music supervisor, and star of the 2004 indie Garden State, a film that looks increasingly like a modern classic every day. According to the Kickstarter profile, Wish I Was Here was intended as a spiritual sequel to Braff’s breakout, sure to please nostalgic Millennials. His campaign’s financing goal had been a requested two million dollars; in but a few weeks, he reached more than three million.

Though the controversy sparked long overdue questions about the ethics and excitement of crowdsourced financing, the ensuing months have found Braff’s position as a cultural icon scrutinized ceaselessly. Meghan Lewit writes that a similar Kickstarter campaign for the film adaptation of the television series Veronica Mars was treated with reverence while Braff’s suffered very public abuse and criticism. She suggests further that the root of the responsive vitriol was the branding: Wish I Was Here was not meant just as a Zach Braff joint, but as an artist’s latest passion project. And when that artist manipulates the public with Ritalin-laced populist shtick, the exploited public retaliates.

What Devin Faraci considers a “large and hopefully endless backlash,” against Braff’s ubiquity in the media – whether as a filmmaker, actor, playwright, philanthropist, or blogger – has been referred to elsewhere as a kind of public shaming. It remains unclear whether or not Braff’s Hollywood career will survive the storm of humiliation (his film has performed unspectacularly at the international box office), but this particular kind of celebrity treatment has become increasingly visible online in the age of anonymity and troll culture. As Patt Morrison correctly writes, shaming people on the “Interwebz” serves more to correct someone’s behavior than to exact any sort of justice for their imagined crimes. Digital vigilantism runs so rampant, in fact, that countries around the world are working to put the kibosh on such behavior.

International efforts have inadequately addressed the 24-hour cycle of public shame lobbed at famous people who, like Braff, have influenced various mainstream arts. Citing Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of the cultural icon, Hazel James Cole links an artist’s particular interests with the level and range of criticism he or she receives; the more diverse the business ventures, the more sources of hate.1 For Cole, no public figure in contemporary media is as paradigmatic of this phenomenon as the pop musician Kanye West.

Like Braff, West suffers from assaults on his self-image and what is perceived as inappropriate behavior from someone with wide influence and power over the zeitgeist. On the Video Music Awards in 2009, he notoriously stole the microphone from the singer Taylor Swift in order to compliment her (losing) competitor, Beyoncé. National response was immediate and aggressive – the President of the United States, for example, called West, “a jackass,” on live television – but the event has registered only as a blip in the artist’s many criticized ventures. He has been called out for his stances on politics and social change. The fashion shows for his clothing line have resulted in consistent allegations of plagiarism, arrogance, and misogyny. And most naturally, critics from every imaginable scholastic field take umbrage with his music production, videos, and rapping.

As Mark Anthony Neal notes, the intense excoriation West receives from project to project has evolved from simple comment board trolling to widespread rhetorical interpretation – and the result is a distinctly sour relationship to each new work of art. Like Braff, the media cycle has imbued the Kanye West brand with racialized controversy, decontextualized antic behavior, and a vaguely inhuman narcissism.2 As if on cue, the mainstream media responds to each fresh “art piece” with viciousness, name-calling, and, inevitably, exploitative tabloidism.

What Braff and West share is the tendency to capitalize on their significant social capital in order to bring attention to their Next Big Project. The inordinate wealth and egocentric goals these artists also have in common result in their becoming fodder for the outraged masses. It makes sense that the public would transfer their hostility for these types of personalities to a film, an album, or a clothing line. But the line between discursive criticism and outright personal attacks on these modern Renaissance men is increasingly blurry.

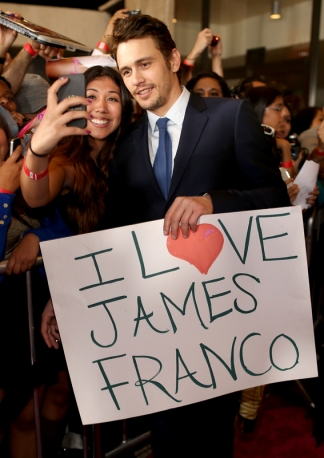

The international media generally acknowledges that the Academy Award-nominated actor James Franco is the face of contemporary multihyphenatism. Though he is best known as a movie star, his many credits in filmmaking, academia, journalism, fiction, and philanthropy have almost no peer in contemporary America. If, as Richard Dyer wrote in 1979,3 the most prominent personalities in the media are also the centers of cultural politics, then Franco is under constant strain to be proverbially impeached. His recent foray into poetry resulted in critics claiming they felt queasy and preparing for the rise of Cthulhu. Similarly, poor reception to a visual art installation in New York City led one writer to pronounce rudely that he should just stick to acting.

It is important to note that these personal attacks recycle the language directed at Franco’s more intimate activities in the tabloids (and that received by West, Braff, Jay-Z, and other totemic cultural figures.) As contributors to a major subreddit noted, Franco was publicly humiliated and forced to embark on an apologetic media blitz for trying to rendezvous with a young woman via the social network Instagram. Considering there was no actual sex or body contact, this particular form of criticism reads like slut shaming or body policing made somehow permissible by the fact of Franco’s great fame.

In the course of humiliating these professional multitaskers, critics and generalized audiences alike participate in a highly offensive and vicious public act. Some have referred to this process as bullying; on a legal level, others have suggested that it might violate the 8th Amendment. The most disturbing element is the fact of crimelessness in these cultural icons, and the lack of distinctions between bad or childish behavior and illegal activities. James Franco’s flirtation with poetry was as harmless as his supposed Instagram scandal, but both received bilious commentary in the public sphere. Zach Braff broke conventions, not laws, when he successfully solicited millions of dollars from a loyal fan base. The nature of public shaming is cruel and unusual– so why do we continue to subject our most prominent artists to such forms of punishment?

Image Credits:

1. Actor and Filmmaker Zach Braff

2. Kanye West and Taylor Swift at the 2009 Video Music Awards

3. James Franco Poses With a Fan of James Franco

Please feel free to comment.

- Cole, Hazel James. “Kanye West: A Critical Analysis of Mass Media’s Representation of a Cultural Icon’s Rhetoric and Celebrity,” in Rock Brands: Selling Sound in a Media Saturated Culture. Elizabeth Barfoot Christian, ed. New York: Lexington Books, 2010. pp. 195 – 211. [↩]

- Rose, Tricia. Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1994. [↩]

- Dyer, Richard. Stars. London: British Film Institute, 1979. [↩]