Access is Elementary: Crossing Television’s Distribution Borders

Christine Becker / University of Notre Dame

“Perhaps even more directly than questions of production or content, the study of distribution cuts straight to the heart of who has access to culture and on what terms.” – Joshua Braun1

While recent U.S. TV industry retrospectives were right to declare 2013 the year of Netflix, I would nominate for runner-up consideration the increased presence of foreign, especially British, imports on U.S. screens. Netflix played a role in that trend, as the streaming service added Channel 4’s Derek to its offerings. Elsewhere, Hulu tried to distinguish itself with imports like Moone Boy and Misfits, while The Returned, Top of the Lake, Orphan Black, and Broadchurch had cable viewers abuzz. Meanwhile, critical acclaim for more narrowly distributed shows like Borgen (available in the US on the satellite channel Link TV) and Black Mirror (on DirecTV’s Audience Network) left some viewers pleading for help with locating them.

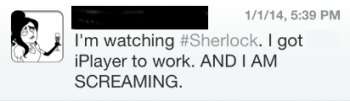

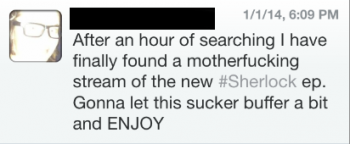

In his tweet, @vogon expressed a desire to stay on the legal side of transnational viewership, but not all are so willing, and it’s getting remarkably easier, technologically and perhaps even morally, to cross that border. 2014 was inaugurated with a prime example via BBC One’s Series 3 premiere of Sherlock on New Year’s Day. The series won’t reach American TV sets until January 19th, when it begins a Sunday night pairing with Downton Abbey on PBS, so no one on American soil, aside from TV critics with screeners, should be able to see Sherlock’s “The Empty Hearse” until then. Yet my Twitter feed revealed numerous Americans tweeting about watching it online.

The lure of early access is strong, driven by such aspects as the cultural cachet of seeing something before others, the desire to participate in a global fan community, and the fear of being spoiled (exacerbated in Sherlock’s case by a spectacular Series 2 cliffhanger followed by an inordinately long hiatus). In some cases, such as Doctor Who’s airings on BBC America, these actions may also be motivated by frustration with domestic presentational aspects, with an egregious example offered by the Christmas Day airing of “The Time of the Doctor,” wherein a commercial break interrupted the introduction of Peter Capaldi’s new Doctor in the middle of the regeneration process. Most fundamentally, there is the desire to not have to wait when one feels it’s not warranted.

Of course, the people whose tweets I have captured here are not the average viewer (and not just because Twitter itself is a niche medium). Most will wait and watch via whatever means outlets that are familiar to them make available, as the success of the shows listed above (and Downton Abbey’s PBS ratings) would prove. But those examples also offer evidence of audiences increasingly wanting to access international content, and a corresponding growth in awareness of “Alternate Methods” becomes inevitable in an age of information sharing.

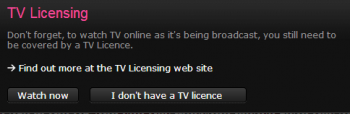

In terms of transnational flows, I assume and hope that we will continue to move in the direction of more, and more timely, legal access, not less. But even as more TV material is becoming available online in the US, it’s often tied to pay TV subscriptions, with inconsistent access based on provider agreements. As an example, ABC’s recent move to reward only some pay TV subscribers with earlier access to time-shifted shows online raises fundamental questions about the public responsibility of those licensed to use the airwaves. In the UK, in contrast, open online access appears to be growing, and in the name of public service, even if there is still a measure self-preservation behind that. Specifically, the BBC recently announced plans to expand availability of shows on its iPlayer service, and this strategy seems to be key to the corporation’s efforts to defend the viability of its license fee funding model in the digital age. It is quite striking, especially in comparison to U.S. examples like HBO Go, how easy it is to access iPlayer content, even from outside the UK. With the assistance of a VPN proxy to convince iPlayer that the user’s computer is in the UK, one needs only to click play, no license fee authentication required. Surprisingly, it is actually legal for Britons themselves who are not paying the license fee to watch time-shifted shows on the iPlayer, as long as they don’t own a television set and watch nothing live.

I have to assume that few non-license fee payers, British or otherwise, linger for more than a few seconds over the moral decision to click “Watch now” on live iPlayer content. Michael Z. Newman has written of how some viewers morally reconcile illegally accessing TV content online, particularly based on a conception that network TV is “free.”2 Such justifications get much more complicated with BBC content, where it’s not corporations but individual people who have helped underwrite the content. But again, a mere button-click does not pose much of a obstacle to make you think about those consequences. I can’t imagine the BBC will be this lax about online access forever, but as someone who researches and teaches British TV, I would happily pay the license fee if given the opportunity to do so. This a commonly expressed sentiment: make content available to viewers legally and conveniently across devices they prefer, and they will access it that way.

But the BBC cannot substantially open up global subscription possibilities without undercutting either its domestic funding logic or BBC Worldwide’s business model. Indeed, the most fundamental bottom line to these transnational flows is how geographically-specific licensing agreements are violated by unfettered online access. I have little reason to watch Doctor Who on BBC America or Sherlock on PBS if I can access those shows directly from iPlayer, especially if I can then use Airplay or Chromecast to throw my laptop screen onto my TV set. And due to such factors as publicity needs and differing scheduling and programming practices for outlets, day-and-date international releases are not always feasible.

To combat piracy, it’s prudent for distributors to make all content more easily accessible legally, yet to do so broadly with transnational content puts into jeopardy global distribution contracts and the substantial economic advantages of controlling content geographically. This issue is as old as broadcasting itself, of course. As Michele Hilmes’ work has explored, national borders have always been essential to broadcast policy and economics yet also challenging to police.3 The very technology of broadcasting – the airwaves, the ether – makes strict geographic definition difficult, and the Dr. Brinkleys and Captain Leonard Plugges of history show how borders can be effectively transgressed. The modern internet and its “tubes” are less diffuse than the radio airwaves, yet geographic definitions are still difficult to maintain, and individual users have more power than they ever did in the broadcast era, as a simple VPN proxy can trick a geo-fence and enable spectatorial forms of illegal immigration around the entire globe.

Such circumstances are part of larger forces pushing television further along the path toward what Derek Kompare has called the shift “from flow to file,” as we move from strategically scheduled bundles of programs and interstitials on branded outlets to discrete shows “made available directly to individuals in small packages on an ad hoc basis.” 4 Comcast, the BBC, even Netflix all have a substantial stake in maintaining today’s outlet-based infrastructure for tomorrow’s distribution of content, but the grounds on which that control is secured will only shift more as we go forward. Committed audiences willing to dig deeper to consume new content and satisfy individual tastes might increasingly seek out “Alternate Methods,” leaving distributors scrambling to respond, while niche channels may find it lucrative to rely on distinguished imports to define their outlets. Looking forward, I can’t imagine we’ll ever get to a point when anyone will be able to legally access anything from any country as they see fit.5 There is too much at stake for media companies in tightly controlling avenues of distribution around preferred outlets, a fundamental linchpin of the corporate dominance of media industry history. The current era is witnessing only one round of an ongoing fight between content’s gatekeepers and viewers seeking to access that content on their own terms and without borders.

Image Credits:

1. Tweets obtained with users’ consent.

2. IPlayer

Please feel free to comment.

- Joshua Braun, “Transparent Intermediaries: Building the Infrastructures of Connected Viewing,” Connected Viewing: Selling, Streaming, & Sharing Media in the Digital Age

Jennifer Holt and Kevin Sanson, eds. New York: Routledge, 2013, Kindle Edition, paragraph 13. [↩] - Michael Z. Newman, “Free TV: File-Sharing and the Value of Television,” Television and New Media, November 12, 2012; 13 (6). [↩]

- Michele Hilmes, Only Connect: A Cultural History of Broadcasting, Cengage Learning, 2010, 3rd edition, and Michele Hilmes, Network Nations: A Transnational History of British and American Broadcasting, New York: Routledge, 2011. [↩]

- Derek Kompare, “Flow To Files: Conceiving 21st Century Media,” presented at Media In Transition 2, Cambridge, MA, 11 May 2002 and posted on academia.edu: https://www.academia.edu/2807306/Flow_To_Files_Conceiving_21_st_Century_Media. [↩]

- For more on digital distribution and reception issues, see Chuck Tryon, On-Demand Culture: Digital Delivery and the Future of Movies, Rutgers University Press, 2013, and Holt and Sanson’s Connected Viewing, cited above. [↩]

Thanks for a great piece. You are absolutely right that the economic models of international distribution are pulling against the promises of digital technology. In the UK, US content has become increasingly positioned as premium content for expensive subscription (and occasionally pay-per-view) channels meaning that while much has been made about simultaneous global release dates for content I find I am having to wait a lot longer for much of the US content that I’d like to watch, some of which will never come to a channel available on my basic cable subscription service. I agree that I can’t see this changing any time soon.

I enjoyed reading this piece. I agree with the issues that were brought up. I understand the problems that could arise if BBC were to allow global subscription but I still agree with my fellow TV viewers I want to see what I want to see. I have to admit a laughed a bit while reading this piece especially the statement by Soph where she said ” the most disappointing statement of the 21st century; is unavailable to stream.” I can say that I recently experienced this when I wanted to view the 4th Season of a Canadian show, of all things, and when I clicked play it said not available to stream, oh so frustrating. Reading this piece helped me to understand, a little bit, of the reasons why networks do that and I don’t see me being able to succeed in viewing these shows legally in the states before they are out on DVD, Netflix, or Hulu.

While British TV has been seeping into the American consciousness for a long time, the past few years have brought the issue of transnational broadcasting to a crisis. There has always been a certain level of crossover in American and British television programming, but for a long time we were content with the very limited offerings we received on each side of the pond. Of course, this contentedness could more aptly have been called a lack of options. Even in the 1990s (when I was growing up with British TV-minded parents) we watched whatever Masterpiece Theatre and DVD box sets could provide us. But with the internet becoming not only a daily reality but a veritable lifestyle, everything has shifted, particularly what a TV viewer has come to expect. Nowadays, we know exactly what we’re missing. In fact, it’s hard to avoid – and with the increased risk bordering on a guarantee of spoilers comes the sense of entitlement that modern TV viewers have come to feel. Some would say we have a right to timely programming, regardless of whatever broadcasting regulations networks of all nations have to deal with. If PBS is going to delay the premiere of Downton Abbey by four months (necessitating the highly unseasonal viewing of the Christmas special in February), viewers will take matters into their own hands. Anyone savvy enough on the internet to know how to illegally stream media will most likely be involved enough online to make the avoidance of spoilers impossible. Thus, the moral choice fades into a cloud of righteous indignation – how could anyone really expect a true fan of Downton Abbey to wait that long for new programming, especially when the new season will most certainly be ruined for them before PBS even airs the premiere? Suddenly, illegal streaming becomes the measure of a true, dedicated fan.

The increasing validation many feel for going outside the law in pursuit of television is part of the fan culture movement that is coming to dominate entertainment. It’s not enough to just watch a show – one has to talk about it too. In fact, as Andrejevic remarks in “Watching Television Without Pity: The Productivity of Online Fans,” sometimes the program itself is a mere excuse for further fan engagement after the episode airs. And if TV is just the first step in a more meaningful and interactive process, how can we be expected to wait around for American networks to sort out their business deals while the internet frenzy dies down? Fandom is an international entity, so Americans will miss out on the initial reactions of British fans (as well as the weeks of discussion that will follow), and join the party long after many have moved on. While fans seek to globalize the television experience, networks localize. There are obvious legal and economic rules for why television can’t be internationally simulcast at all times, but business models all too easily fall by the wayside of the juggernaut that is fandom. It’s even harder to follow the rules when there are instances of simultaneous international airing. The recent 50th anniversary special episode of Doctor Who was broadcast on the same day in 94 countries. When we know it can happen, given the right set of circumstances and incentives, it’s harder and harder to understand why it isn’t happening more often. And in comes vigilante justice in the form of self-justified illegal streaming. While the relative morality of this choice can’t be definitively settled, the trend towards illegal streaming is unlikely to change so long as the concurrent trend of international fan engagement continues as well.