“Why Do They Make It So Extreme?!” On Videogame Glitches and Joy

Carrie Andersen / University of Texas at Austin

Laddergoat flies into the sky.

In a 2009 YouTube video called “Laddergoat,” a videogame avatar encounters a small creature of unknown origin. The player is perplexed by its identity: “Wait, is that a deer?” he asks. The creature dodges his avatar in spite of his efforts to identify the animal. “Come on, let me see your face!” he shouts. Finally, he thinks he has cornered the creature near a ladder, until the animal inexplicably floats into the sky up the ladder, its hooves toddling along as if it were walking. The player erupts into laughter, and it is impossible not to laugh with him. He has found only a minor glitch, but its ability to incite joy is anything but inconsequential. As of this writing, nearly seven million people have watched the clip, seen below.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ggB33d0BLcY[/youtube]

Dopefish finds Laddergoat

“Laddergoat” was my introduction to a niche YouTube celebrity named Dopefish, a Swedish gamer who has recorded hundreds of videos that feature him playing and laughing about videogames. The most popular of these videos–those that have garnered upwards of 50,000 or 100,000 views–center on Dopefish’s encounters with unexpected videogame glitches.

Contrary to Dopefish’s experience, the glitch in popular media is often framed as anything but an occasion for joy. In Robocop (1987), a robot designed to restore order to Detroit’s streets called the ED-209 experiences technological difficulties and eviscerates a member of the Omni Consumer Products Board of Directors. “I’m sure it’s only a glitch,” says another member of the board, nonplussed.

[dailymotion]http://www.dailymotion.com/video/xfiky4_robocop-only-a-glitch-scene_shortfilms[/dailymotion]

The Matrix (1999) features the glitch in a harrowing moment when enemy robots maliciously alter a simulation meant to pacify humans who are being farmed by those robots for energy. That manipulation, the glitch, inevitably results in violence against those humans as it does in Robocop. And even children’s programs are not immune from the catastrophic glitch: Adventure Time (2010), a Cartoon Network television series, features an episode entitled “A Glitch is a Glitch” where the villainous Ice King creates a bug in the world’s source code that could destroy matter itself. The apocalypse looms thanks to a technological blip.

Unsurprisingly, videogame designers and coders have been concerned with creating virtual, realistic, immersive spaces where the glitch is similarly undesirable (although perhaps not as world-ending). As designer Toby Gard writes, “When we are creating worlds in games, immersion is only possible for the player if we can convince the players that the space is authentic (whether stylized or not.).”1 The code that underlies the videogame holy grail—the authentic, immersive gaming world—is demystified if a character or background looks warped in such a way that players no longer buy into the illusion.

These glitches clearly disrupt the illusion of the simulation’s fidelity to real life.

In line with Gard’s concern with the immersive virtual space, media scholar Eugénie Shinkle describes how videogames ideally use sophisticated simulations to hide their intricate, sublime technological codes, but failure events—glitches—make these codes visible and thus rupture bonds between player and game space. Consequently, players can lose control, meaning, and their senses of self. The game shifts from being a virtual arena for exercising player agency and posthuman subjectivity back into a clunky object, as lifeless as any piece of furniture.2

In all of these cases, glitches occupy a space on a spectrum that spans from the minor irritation to the colossal fuck-up. But constructing the glitch so negatively ignores the real pleasure that can arise from encountering a hiccup in the technological system. What happens when failure events, rather than provoking a loss of our post-human selves or the literal end of the world, instead evoke happiness?

Enter Dopefish. Dopefish is ostensibly unconcerned with the kind of immersive play that game studies scholars and game designers often assume to be the default mode of play. He seems to experience no personal catastrophe when he discovers that the goat can float into the air, except for the stomach pain that arises from laughing too hard.

Nor does he find his departures from diegetic realism problematic when playing The Political Machine, a political simulation game released in July 2012. The game’s central conceit involves choosing or creating a character to run in the 2012 presidential election, which requires traveling around the nation, making speeches, seeking endorsements, running advertisements, and more. Dopefish discovers (to his delight, naturally) that the game somehow enables the creation of characters with unfathomably grotesque facial and bodily features that could never conceivably happen in real life. “Why do they make it so extreme?!” Dopefish shrieks at the absent game designer. A good question. Being able to detach a character’s ear from his or her face does not a realistic simulation make.3

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JjEixQLV0FQ#t=95[/youtube]

Dopefish plays The Political Machine

And Dopefish is not the only gamer to zero in on the joy of those glitches that pull a game away from realism into ludicrousness. Countless others post videos of themselves playing games and laughing at coding errors on sites like Reddit’s Contagious Laughter forum, a few notable examples you can find here. But rather than simply offering a recording of their gameplay, these players publicize these glitch encounters in a way that emphasizes that joy. In addition to the sound and music of the game, the videos’ audio tracks inevitably include players’ own laughter-laden responses to the glitch. In these videos, what the glitch does is less important than the emotional response it evokes.

For those designers seeking to create an immersive and participatory virtual space, the Dopefish mode of gameplay throws a spanner into the works. These gamers undertake a process of playing that rejects immersion on its face. But the practice of seeking, exploiting, and delighting in glitchy aspects of videogames may also constitute an even more engaged playing experience. Mining these bugs requires time and energy, but finding and enjoying a glitch, for gamers like Dopefish, is a worthwhile payoff.4 Perhaps Dopefish is pointing to a style of play that, like the glitch itself, is unexpected, uncontrollable, but nonetheless has some unintended utility.

But what is that utility?

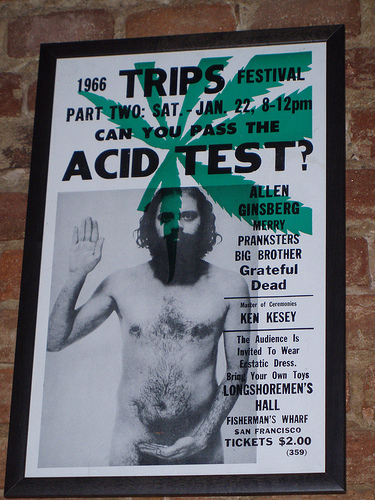

An easy-but-probably-wrong answer: Dopefish’s mode of play constitutes an intentional form of political-cultural resistance, the kind of joyful fuck-with-the-system imperative that underlay whimsical (but not apolitical) activists like the Yippies and the Merry Pranksters of the 1960s. But I think it would be a mistake to envision Dopefish as a nouveau Ken Kesey with some latent political activist bent.

Not Dopefish.

An alternative answer: by exploring why we laugh at the videogame glitch, we can perhaps learn what this form of engagement reveals about our relationship with technology and simulations. I’ll close this piece with a few possibilities that draw on three theories of humor.

ONE. Dopefish’s videos, and those videos like his, call attention to the fact that even the most polished systems remain fallible and junky when compared with human capabilities, in spite of technoutopian rhetoric that argues otherwise. Thomas Hobbes might as well have been referring to The Political Machine when he wrote in Leviathan that laughter emerges from “the apprehension of some deformed thing in another, by comparison whereof they suddenly applaud themselves.”5 Perhaps Dopefish, by highlighting the grotesqueness of technology that glitches make visible, instigates some joyful Hobbesian notion of superiority not over another human (as Hobbes writes), but over that technology. Man remains high above machine if the machine inexplicably permits this distortion in the guise of authentic simulation:

“Why does this even exist as an option?” Dopefish asks. Who knows.

TWO. Immanuel Kant writes in Critique of Judgment, “laughter is an affection arising from the sudden transformation of a strained expectation into nothing.”6 Our expectations of a probable outcome in The Political Machine and in “Laddergoat” are ruptured amidst Dopefish’s cackles. Attending to the joy of the glitch indicates how vast the gulf is between what we expect of technology—and of simulations—and what it actually offers us. We expect a political candidate that looks like a person. We get a candidate with an enormous inside-out nose. We expect a goat that cannot fly. We get Laddergoat.

THREE. Finally, Dopefish might be poking fun at the view that videogames can actually blend subject and object through sophisticated simulation or, these days, through embodied modes of play. Henri Bergson suggests that humor emerges from an incongruous merger of the mechanical and the living. The comic persona comes “from the fact that the living body [becomes] rigid, like a machine,” and the incompatibility of the body-machine relationship is ultimately both laughable and evidence of man’s superiority over the mechanical.7 Dopefish’s response to The Political Machine might gesture to the absurdity of yoking man to machine whether that man is created in simulation or living in real life. The candidate that Dopefish creates in the game is at once inhuman and farcical; so, perhaps, is a human operating an XBox Kinect or a Nintendo Wii with bizarre and uncannily robotic gestures:

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b1vBbVlDDaE[/youtube]

An unintentionally (?) funny demonstration of the XBox Kinect

Regardless of the underlying reason for the laughter that ensues from the glitch, demystifying those systems we often hold to be immune to melting down reminds us that, yes, electronic blips can still happen in our technologically-infused world. Simulations can be incredibly realistic and immersive, but they are rarely perfect. And those mistakes, if they aren’t catastrophic, are really, really funny.

Image Credits:

1. Laddergoat flies into the sky. Screen capture by author.

2. These glitches clearly disrupt the illusion of the simulation’s fidelity to real life.

3. Not Dopefish.

4. “Why does this even exist as an option?” Dopefish asks. Who knows. Screen capture by author.

Please feel free to comment.

- Toby Gard, “Action Adventure Level Design: Kung Fu Zombie Killer,” Gamasutra, May 7, 2010, accessed September 23, 2013. [↩]

- Eugénie Shinkle, “Videogames and the Digital Sublime,” in Digital Cultures and the Politics of Emotion: Feelings, Affect, and Technological Change, ed. Athina Karatzogianni and Adi Kuntsman (New York, Palgrave McMillan, 2012), 94-109. [↩]

- Caveat emptor: Dopefish has a tendency to use some rather indelicate racial language. But his attention to the absurd amount of customization The Political Machine offers remains nonetheless worthy of analysis. [↩]

- I’m speaking here about players who encounter the glitch serendipitously. There is, however, a mode of play wherein players use modification software to deliberately insert a glitch into a game (and then, consequently, laugh about the effects). See this video from Vinesauce where the player creates entertaining corruptions in Donkey Kong Country for the Super Nintendo system, or this “Best NES/SNES Corruptions” compilation by the same player. [↩]

- Thomas Hobbes, “Of the Interior Beginnings of Voluntary Motions,” Leviathan (1651). [↩]

- Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgment, trans. J.H. Bernard (London: Macmillan, 1914), I.I.54. [↩]

- Henri Bergson, “Laughter: An Essay on the Meaning of the Comic,” trans. Cloudesley Brereton and Fred Rothwell (New York: Macmillan, 1914), 49. [↩]

Fascinating exploration of glitch-mania in modern media!

Oh, as Dopefish might wonder, why do we do this? (Why do we lose it when representation implodes on itself)? Perhaps it’s revealing about our culture’s relationship to simulation that we take such pleasure in discovering accidental unravelings in a game (or movie or whatever)? As such times, there is a moment of deliriously uncontrolled possibility that suddenly emerges in the control society… A hole in the fence presents itself: subversion beckons…

Surely medieval monks took far less demented joy in finding errors in illuminated manuscripts? But who knows? Maybe the Book of Kells has a subtle glitch somewhere that prompted a mead-fueled laugh-fest among the Celtic brothers one chilly night ten centuries ago…

Thanks to Carrie (and Dopefish) for prompting such thoughts in this well written essay.

Randy – thanks for the note! I have no doubt that the Celts enjoyed their typos as much as Dopefish enjoys character creation :)

what’s also interesting to me (and what I didn’t have the chance to discuss for brevity’s sake) is the fact that there’s a cadre of players who, rather than finding those accidental unravelings, deliberately corrupt the code to create an entertaining glitch. that’s a different kind of pleasure than that provided by the sudden, unexpected hole in the fence. maybe it’s Hobbes 2.0, a moment of pure mastery over the code wherein we create some deformation in another and regard ourselves as really superior. I don’t know. additional food for thought.

Pingback: Grad Research: Carrie Andersen writes on videogame glitches and joy in Flow « AMS :: ATX