Americanizing Bachata: Romeo/Aventura and Transformation of a Dominican Identity

Nelson Santana / CUNY Dominican Studies Institute

Without doubt, Anthony Romeo Santos is both the most successful and popular person of Dominican ancestry to penetrate the mainstream Spanish-speaking U.S. American market in music. Dissimilar to Ricky Martin and Shakira – artists who have successfully “crossed over,” making the transition from Spanish to English markets in music – Santos has yet to make such transition and is in no rush to cross over. Ironically, Santos’ success alongside his former Aventura band members Henry, Lenny, and Mike and his current success as a solo artist, can be attributed to his blend of English and Spanish in his songs. Santos has recorded with mainstream artists including Usher, Ludacris, Wyclef Jean, Little Wayne, Don Omar and Thalía, among others. Perhaps most notable about these recordings is that some of these songs were recorded in the genre of bachata – a music that has been ostracized since the moment it was born and became part of Dominican society and was ingrained in Dominican identity. Aventura and eventually Romeo as a solo artist, have been successful in the mainstream Spanish-speaking U.S. music market because they altered bachata’s traditional schema by incorporating their U.S. American identity into their music.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eFpRY8IkbNA[/youtube]

Bachata is the Dominican blues. In the early years people were ashamed of bachata since it was the common belief that it was the music of the subaltern: society’s degenerates who looked for a good time in brothels and bathed themselves in liquor. In fact, people were careful to play bachata at a minimal level as to not alert their neighbors of the playing of such music in their homes. For decades merengue was the music of choice of the Dominican people. It became the music of choice during the bloody 31-year dictatorship of Rafael Leonidas Trujillo, an era in which many other native genres flourished.1 Music is powerful and Trujillo understood this concept. Merengue became Trujillo’s personal marketing tool when he made it the national music genre. In becoming the national music of the Dominican Republic, the nation’s elite placed this genre on a pedestal, above all other music, while bachata was relegated to the lowest possible position.

When it traveled to the United States, bachata was actually embraced by the immigrants who imported this cultural product (bachata legend Teodoro Reyes reaffirms this in the documentary Santo Domingo Blues: los tigueres de la bachata: The Story of Luis Vargas (Santo Domingo Blues).2 Oddly enough, bachata made its ascension to the mainstream Spanish U.S. market in the early to mid- nineties which coincided with the emergence of Anthony Santos (not to be confused with Anthony Romeo Santos) and the subsequent success of his albums. Even in the mid to late nineties bachata music was rarely played on U.S. radio stations. Eventually disc jockeys that worked in radio stations such as La Mega in New York took notice of bachata’s rising popularity among non-Dominican Latino groups and sporadically began to play bachata on the radio. In fact, the most popular disc jockey in the New York metropolitan area is Alex Sensation, who is of Colombian ancestry. His success is greatly attributed to the playtime he has given to mixes of Dominican music, especially bachata and merengue. Even though it was the more traditional bachatas of bachateros like Luis Vargas and Raulin Rodríguez that began to captivate audiences and brought a more profound audience to radio stations that cater to Latinos, it was not until bachata became more “Americanized,” that the genre began to penetrate mainstream Spanish-speaking markets in the U.S., with the group Aventura leading the charge.

Success is something that is difficult to quantify. One person’s definition of success will more than likely differ from that of his or her peers. The 21st century has seen a boom of Dominican people in U.S. media in both Hispanic/Latino and U.S. American markets. In the United States, one tool that is utilized to measure success in music is Nielsen SoundScan, which tracks album sales. Billboard, a trade magazine that annually produces the Billboard Music Awards and Billboard Latin Music Awards, respectively, utilizes Nielsen SoundScan to track album sales and also track song airplay on the radio and song downloads, among many other things. Aventura’s fans demonstrate their purchasing power in concert and album sales. In 2009 Aventura’s album The Last spent 27 interrupted weeks as the top-selling Latin album in the United States, outselling mainstream Latin American artists such as Wisin y Yandel, Daddy Yankee and Vicente Fernández. The following year the group garnered nine Billboard Latin Music Awards for The Last.

The formula that made Aventura successful has been copied by subsequent bachata acts including X-treme, Optimo and Nueva Era among others. Even Prince Royce, who in 2013 took home multiple Latin Billboard awards, too has applied Aventura’s formula. This is referred to as

Aventura’s formula because this was the first group to actually apply the formula and be successful.

What is this so-called formula? Aventura is comprised of three second generation Dominicans: Romeo, Lenny and Max, while Henry is part of the 1.5 generation since he was born in Moca, Dominican Republic, but migrated to the United States at an early age. The identity of each member was formed while living in the United States. They grew up exposed to Dominican culture (in the case of Romeo, Dominican and Puerto Rican as his father is Dominican and mother Puerto Rican) and U.S. American culture. Aventura – and their members through their individual music projects – incorporates elements of hip hop, R&B, and rock music among other genres. Also, their albums incorporate songs that are sung exclusively in Spanish, English and sometimes both languages. The group’s first hit single in 1999, “¿Cuando volverás” (When Will You Return?), has two versions in the album Generation Next; one version in Spanish and the second in Spanish and English, thus breaking the lyrical traditional norm of Spanish-only bachatas. Romeo and company quickly realized the significance of this historic moment; in 2002 they released the single “Obsesión” (Obsession) which began the group’s meteoric rise to greatness, thus cementing their legacy as one of the greatest, if not the greatest, Dominican group to be formed outside the Dominican Republic. Another crucial component of this formula is that Romeo, the principal songwriter, writes songs that touch upon subject matters that are taboo among people who trace their origins to Latin America. The song “No lo perdona Dios” (God Will Not Forgive) – also in the album Generation Next – is about a female who aborts a fetus. Singing about everyday occurrences that are specific to people who comprise second and 1.5 generations of Dominicans living in the United States and singing in the language of these people is the formula that has made possible Aventura’s success.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d6DIleLYlF8[/youtube]

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x_KJjT2F7-0[/youtube]

Children of the Dominican diaspora seek refuge in Aventura’s music. Aventura sings about abortion, heartache, fatherless children, and other issues that specifically affect second and 1.5 generations. If anything, Aventura is a reflection of their audience. Similar to bachata’s earliest consumers, Aventura’s listeners are excluded from the hegemonic power structure and instead bond with their marginalized peers through Aventura’s music. Aventura preserves bachata’s traditional form of being a music of the oppressed by denoting the struggles constituted in the subcultures where bachata is listened.

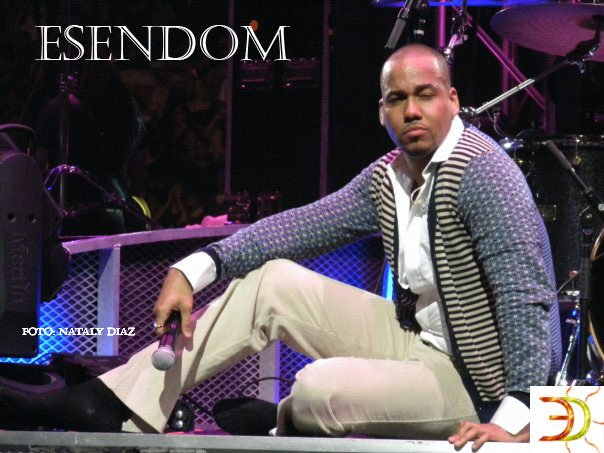

Image Credits:

1. Anthony Romeo Santos, photo by Nataly Diaz

Please feel free to comment.

- Pacini, Deborah. “Social Identity and Class in Bachata, an Emerging Dominican Identity.” Latin American Music Review / Revista de Música Latinoamericana. 10.1 (1989):69-91. Print. (72). [↩]

- Santo Domingo Blues: los tigueres de la bachata: The Story of Luis Vargas. Dir. Alex Wolfe. Santo Domingo Blues, Mambo Media, 2004. DVD. [↩]

Thank you for your insightful and informative article! Most pointedly, your discussion of bachata music’s counter-cultural proliferation under Trujillo’s regime struck me as noteworthy considering the subsequent Americanization of the form that you discuss in your analysis of Aventura. While you describe the group’s songs as socially/politically resonant for the Dominican diaspora in your conclusion, I wonder, how do you feel that Romeo Santos and his group reconcile the use of English lyrics and other American stylizations in contemporary bachata music with the United States’ support for Trujillo at the time of bachata’s “subaltern” popularization? In distinguishing Romeo Santos from “cross-over” performers, do you think that he critiques American interventionist/imperial policy through his “Americanization” of a traditionally marginalized Dominican art form in a way that his contemporaries do not?

Pingback: Seinfeld’s Web Series and Grading Video Essays: Two New Publications | MediAcademia

Pingback: Raulín vive un buen momento

Pingback: Romeo alcanza primera posición

Querido Nelson,

My name is Andre Veloz, a still unknown female Bachata singer residing in the Bronx. Your name and then your articles came to me thanks to Deborah Pacini. Please contact me. My e-mail is andrebachatera@gmail.com

Wishing you the Best,

Andre Veloz