If Looks Could Kill: Postscripts and Afterthoughts to “Visual Riposte”

Paula Amad / University of Iowa

In an age in which the digital interface is supplanting real face-to-face communication, the simple impact of being looked in the eye by a person in the flesh has acquired even more forceful registers. And yet digital technology is also revitalizing the aura of face-to-face communication in video chat programs such as Skype and FaceTime in which, if one can resist staring at the picture-in-picture video of oneself, one can have a near aligned, eye-to-eye virtual chat with another person. Likewise, media before the digital (photography and film) were also haunted by the specter of face-to-face communication. From the fixed, frontal pose of diverse, nineteenth-century photographic formats (such as daguerreotype portraiture to police mug-shots) to the near ban on actors looking into the camera in the classical Hollywood film style, the presence or absence, whether voluntary or involuntary, of a look into the camera (and with it a simulation of face-to-face exchange) offers one of the defining structures of modern visual representation. My article “Visual Riposte” explores the debates around how to interpret looks into the camera, focusing on early nonfiction films embedded in cross-racial exchanges, and using as a case study a little known group of films made by Father Francis Aupiais in colonial West Africa around 1930.

In addition to wanting to investigate the challenging series of looks into the camera in Aupiais’s neglected films, the essay developed in response to three concerns: a self-critical desire to interrogate film studies scholars’ investment in the return of the gaze; a personal interest, related to my own intellectual roots in postcolonial theory and early cinema studies, in querying the unfinished business of postcolonial theory’s encounter with cinema; and, finally, an interest in tracing the more generalized manifestations of a visual riposte ‘turn’ in media culture generally.

The moment a mode of interpretation is repeated to the point where once summoned, the reader can predict the outcome of the analysis, that method deserves sustained questioning. “Visual Riposte” developed in response to my own concerns with one such hermeneutical habit in film studies, the tendency to interpret the look into the camera as a disturbing or resistant practice. While this tendency has a long and complicated history involving diverse film modes, movements, and practices that contain looks at the camera, I focused on one recent hotspot of return gaze criticism: instances in nonfiction film from the silent cinema period where the person returning the gaze is historically coded as a racial Other. I began from the supposition that although I want to believe in the disruptive potential of looks at the camera I was also not so sure they return anything except the viewer’s/critic’s own desires to rescue subjects historically victimized by the camera’s disciplining gaze. I ended somewhere nearer recognizing that this narcissistic approach to history (the past mirrors the concerns of the present) is not entirely politically delusive or historically irresponsible, ultimately suggesting the interpretive habit needs to be reformed rather than rejected outright, especially as it appears that fascination with the returned gaze is not going away anytime soon.

Evidence of an expanded interest in looks into the camera appears in a range of sites and practices where the dynamics of visual riposte are being activated often for the purpose of memory work, broadly speaking. As touched upon in my essay, these include the now common set-up in televisual documentaries in which we view archival footage of a subject looking into the camera via the proxy of that subject’s descendant viewing the same footage, often in a domestic setting whose mise-en-scène stages an encounter between the past and present enabled by cross-media return gaze sightlines. What I did not get to mention was that these examples of inter-generational looks across time ironically appropriate an earlier, postcolonial-inflected version of return gaze poetics found in reverse ethnography’s self-conscious intent (usually on behalf of historically oppressed peoples) to counter the West’s conventional representation of racial Others. Varieties of reverse ethnography in film practice centered around returning the oppressor’s cinematically-mediated gaze appear in Nanook Revisited (Claude Massot, 1990), in which Allakarialuk’s descendants watch and speak back to a video of Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North (1922), as well as in Rouch in Reverse (Manthia Diawara, 1995), whose title indicates Diawara’s intent to overturn Rouch’s approach to the ethnographic subject, an approach which, Ousmane Sembène claimed, tended to film Africans as though they were insects. Something quite different, however, than cross-racial negotiation occurs in the BBC’s The Lost World of Mitchell and Kenyon (2004) in which white descendants speak back to images of their white, Edwardian relatives. In this latter instance the reversal occurs across a generational, not racial, divide and the major barrier to reconciliation with the image of one’s relative occurs across a sentimental rather than traumatic register. 1

Other important sites for the migration of a return gaze mode include the film museum, where a cinephilic, star-focused fascination with returned gazes is often on show. This tendency finds its ultimate embodiment in Berlin’s Film Museum. The permanent exhibition space of Germany’s premier museum to the history of film and television is comprised of a number of rooms that seek to educate the visitor on standard topics such as Weimar cinema, Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927), Marlene Dietrich, and cinema under National Socialism. But before entering these more traditional informational-based rooms the museum visitor must move through an experiential-based hall of mirrors, choreographed as an architectural and visual monument to the returned gaze. This Caligari-esque ante-chamber is comprised of silver-metal floors, mirror-paneled ceilings, and multiple screens placed at different angles each featuring a looped close-up of a famous German star looking towards or sometimes into the camera. Moving through the room’s snaking passage, the visitor is trapped seductively in a web of looks, eyes gazing longingly at, behind, on top of, and through you to an infinite, mirrored relay of others’ (including your own) gazes.

Indeed, the Berlin Film Museum’s cinephilia of the face speaks to another critical discourse in which we can see a variant of the return gaze hermeneutic, in historical and theoretical treatments of the face in film studies. In my own contributions to that discourse in Counter-Archive I connected Jean Epstein’s fascination with the figure of the magnified screen face, which he describes in his 1921 essay “Magnification” in terms of meteorological scale (the face as earth), with human geography’s explicit, photographically mediated revision of the earth as a face in the writings of the French geographer Jean Brunhes. 2 That filmmakers and geographers were both experimenting at the intersection of visage (face) and paysage (landscape) indicates more than a playful question of scale. The proto-environmental ethics of the latter posture (seeing the earth as a face) are borne out, for example, in the long, if obscured, tradition in aerial photography that endeavors to open the view from above onto the ethical potentiality of a returned gaze mode detected in images in which the ‘earth looks back’ – a question I am exploring in my current project on aerial vision across photography and cinematography. 3

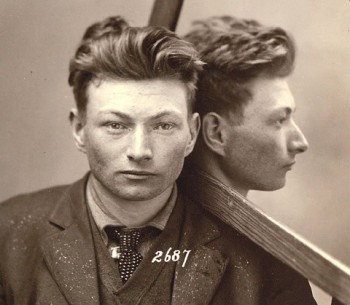

The pedagogical applications of these questions continue in the undergraduate course I am currently teaching, titled If Looks Could Kill, in which we are exploring a variety of moments, modes, and debates in the history of photography in which returned gazes played a central if ambiguous role. Recently, working through Errol Morris’ book on photography, Believing is Seeing: Observations on the Mysteries of Photography (2011), we turned to the documentary filmmaker’s own contribution to the returned gaze phenomenon, the Interrotron camera rig. Responsible for giving his interviews a particularly unsettling style built upon an intensification of eye contact, the Interrotron set-up allows interviewer and interviewee to be in separate rooms while conducting a ‘face-to-face’ filmed interview using connected cameras. Put simply, the rig allows the interviewee to be looking simultaneously into the eye of a camera and a person (albeit filmed), thus bringing the filmed subject’s gaze in closer proximity to the human-intended destiny of the return gaze argument (where the camera stands in for the cameraman and spectator). The difference, of course, is that the look into the camera in Morris’ films is no longer fleeting or accidental, as it often is when found in early nonfiction cinema. It dominates the interview sections of his documentaries, to the point where looks away from the camera in a Morris interview are now seen as being disruptive. The lure of direct eye-to-eye contact in the Interrotron occupies an interesting position vis à vis another returned gaze phenomenon commented upon by Morris, a peculiar genre of mug-shots featured in Least Wanted: A Century of American Mugshots (2009) which incorporate a mirror so that the suspect is captured frontally and in profile in the same photograph. These disturbingly self-reflexive, quasi-modernist mug-shots resemble a sort of meta-critical warning about the return gaze interpretive phenomenon. On the one hand, the bifocal portraits give us a fuller, more instrumentally replete, and thus traceable perspective upon the subject’s face. On the other hand, we are given a split and even more unknowable subject: the outward gaze of the face in profile mocking the critic’s desire for exchange with the camera-focused face, reminding us of the policeman lurking in all our interpretative desires.

Image Credits:

1. Least Wanted: A Century of American Mugshots

- The exception to this would be those interviews with descendants heavily dominated by memories of the hardship of Edwardian working class experience. [↩]

- Counter-Archive: Film, the Everyday, and Albert Kahn’s Archives de la Planète (Columbia University Press, 2010) 270-278. [↩]

- For my essay outlining some of the conceptual stakes of this project within the domain of photographic history, see “From God’s-eye to Camera-eye: Aerial Photography’s Post-humanist and Neo-humanist Vision of the World,” History of Photography, 35.1 (February 2012): 66-86. [↩]