The Afro-Brazilian Public Sphere

Reighan Gillam / University of Michigan

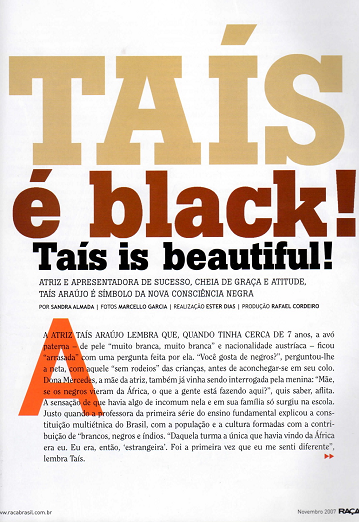

Revista Raça or Race Magazine cover with Afro-Brazilian celebrity Taís Araújo

This is the third and final piece in a series of articles I have produced examining the dynamics of race, blackness, and media in Brazil. The first piece established the visual contours of race in Brazil and described the lack of Afro-Brazilians that appear in the media and the stereotypical roles through which they do become visible. The second piece examined the show Everybody Hates Chris as a television program that presents a foreign incursion into the public sphere. This final piece will draw attention to some Afro-Brazilian media production that disrupts notions of racial democracy or the hegemony of mixed race identities in Brazil.

In his essay “Black Cinderella?: Race and the Public Sphere in Brazil,” Michael Hanchard critiqued Habermas’ idea of the public sphere by describing it as, “the place where the West’s others have been displaced and marginalized, inside and outside of its borders.”1 Using Brazil’s history of black racial exclusion and racism, Hanchard contends that:

Marginalized groups create territorial and epistemological communities for themselves as a consequence of their subordinate location within the bourgeois public sphere. Along these lines, Afro-Brazilians have constructed public spheres of their own that critique Brazil’s societal and political norms. 2

Hanchard goes on to adumbrate an Afro-Brazilian public sphere in religious and carnival spaces. To these spaces I would add visual media as another location in which Afro-Brazilians are mobilizing to produce representations of themselves and critique the hegemonic whiteness and limited images of blackness that have become the norm in Brazilian mainstream media. In this essay I will briefly describe three venues of Afro-Brazilian media production.

Established in year 1996 Revista Raça or Race Magazine has provided a venue in which Afro-Brazilian and other media producers can produce images of blackness and create stories that speak to Afro-Brazilian issues. This nationally circulating, monthly magazine covers Afro-Brazilian celebrities, models, and community leaders who may otherwise go unacknowledged by the national press. The text includes the words negro and black to promote identification with the term and valorize them as identity categories. Kia Lilly Caldwell points out that, “In many ways, the visual representation in Raça have a greater impact on the tone and message of the magazine than do the articles and journalistic content.”3To this end, the magazine includes images of celebrities and ordinary Afro-Brazilians from around the country. For example, the above image shows Taís Araújo, an Afro-Brazilian actress famous for starring in Brazil’s popular telenovelas or soap operas. The text reads, Taís is Black! Taís is beautiful!4 The text and pictures link her with black identity and black consciousness, which works to destigmatize this identity category and promote its use among the magazine’s readers.

The magazine also contains sections dedicated to including the pictures and voices of ordinary Afro-Brazilians. In an October issue of Raça in 2007, the section Diz Aí or Say It states that, “10 public school students in São Paulo say what they think is important to change school for a good formation.” The pictures of students accompany their answers to this question make visibly evident that the voices of people of African descent are made central. Their printed statements allow them to contribute to the conversation about the state of public education and to provide their own views of their educational experiences. Among the quotes from the students, Danillo Tadeu states, “Everything is messy in politics. The changes should start with an increase in the minimum salary. Our parents need a foundation from which to lead us.” Vinicius Borges states, “We need cultural events. The battle is difficult, but if we help ourselves, in the future, the victory can be easier.” By visibly displaying the photos of the students the magazine asserts its commitment to representing Afro-Brazilians and by including the students’ words the spread creates a sphere of dialogue in which students can offer their views of their school system and the challenges that plague it.

On November 20, 2005 TV da Gente or Our TV was launched in the city of São Paulo. This television network was the first of its kind to include the mission to racially diversify televisual representations in Brazil. Jose de Paulo Neto, commonly known as Netinho, an Afro-Brazilian musician and television personality, founded the network and assembled a team of Afro-Brazilian and non-Afro-Brazilian media producers to create and record the network’s programming. They launched the network on November 20, 2005, Brazil’s National Day of Black Consciousness, which celebrates and honors Afro-Brazilians and the life of Zumbi dos Palmares. Zumbi lead a group of fugitive slaves and was captured and killed by the Portuguese on November 20, 1695. TV da Gente’s launch on this day forged for its initiators a symbolic connection between historic and contemporary sources of critical Black resistance to hegemonic forces that sought to marginalize or erase the presence of blackness within the country.

The network’s programming included: Who Knows Clicks – a competition for students to answer black history questions; A Question of Rights – a show informing viewers of their rights as citizens; Class Hour – A Children’s show. The programming featured predominately Afro-Brazilian hosts, but also included White and Asian hosts. The program producers aimed to fairly represent the diversity of the Brazilian population in ways that they thought mainstream television failed to do. Although the network does not seem to exist in its original form in São Paulo, the importance of a television network like this lies in its challenge to the system of network ownership and control that contributes to the limited representations of Afro-Brazilians on television and in the mainstream public sphere. Netinho’s decision to invent, organize, and finance the TV da Gente television network draws attention to the critical need and role of Black business and industry ownership in order to create spaces in which people committed to racial equality can carry out their work.

Another media vehicle directed towards addressing and representing the Afro-Brazilian population in São Paulo is the newspaper Diáspora. This paper is distributed free of charge at different events that address Afro-Brazilians in the city. This newspaper is produced and circulated by Marco Dipreto, an Afro-Brazilian journalist in São Paulo. The paper covers various events that focus on Afro-Brazilians and racial issues. The edition of Diáspora pictured above documents the activities for The Day of Black Consciousness in São Paulo in 2007, such as the Black Consciousness Parade down Paulista Avenue and concerts at the Praça da Sé (Sé square). Although it did not have wide distribution, the Diáspora newspaper documented different activities produced by Afro-Brazilians that rarely made it into national newspapers.

While Race Magazine probably has the widest distribution and the most longevity, it exists along side other media vehicles that are attempting to racially diversify public images. These other media venues struggle for financing, which impedes the endurance of their existence. Thus parts of the Afro-Brazilian public sphere are precarious and survive due to the will of their creators and the availability of funds to sustain limited time horizons of creation. Overall, these acts of media creation and dissemination mobilize the very medium of their marginalization to imagine, invent, and distribute oppositional images, thus creating a mediated presence that is meaningful and affirming of Black people, experiences, and culture. The work and mission of Afro-Brazilian alternative media sustains another front in the fight for racial equality by targeting the aesthetics of power and domination and by making visible what racial equality can actually look like.

Image Credits:

1. Revista Raça or Race Magazine cover with Afro-Brazilian celebrity Taís Araújo, From Author’s Private Collection, Revista Raça November 2007, Cover

2. Taís Araújo cover story, From Author’s Private Collection, Revista Raça November 2007, 21

3. Say It Section of Race Magazine, From Author’s Private Collection, Revista Raça October 2007, 18

4. TV da Gente: A Cor do Brazil (Our TV: The Color of Brazil)

5. Section of Diáspora Newspaper, From Author’s Private Collection, Diáspora November 2007

Please feel free to comment.

- 1 Michael Hanchard, “Black Cinderella?: Race and the Public Sphere in Brazil,” in Racial Politics in Contemporary Brazil, ed. Michael Hanchard (Durham: Duke University Press, 1999), 60. [↩]

- Ibid. 61 [↩]

- Kia Lilly Caldwell, Negras in Brazil: Re-envisioning Black Women, Citizenship, and the Politics of Identity (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2007), 95. [↩]

- All translations were done by the author. [↩]

Pingback: Mixed Race Studies » Scholarly Perspectives on Mixed-Race » Notes on the Racial Contours of Visual Culture in São Paulo, Brazil