Strike Through the Mask: Male Faces, Masculinity, and Allegorical Queerness in Breaking Bad

David Greven / University of South Carolina

In my previous Flow column, I discussed the AMC television series The Walking Dead (2010-present) and the lack of queer representation on this series as well genre television shows as a whole. I also suggested that an allegorical queerness informs The Walking Dead, one that principally emerges, or takes the form, of a denatured, destabilized straight male identity. The lack of queer representation is counterbalanced—but neither addressed nor exculpated by—the queering of straight masculinity.

This essay and the previous one flow out from my current book project (in process), Ghost Faces, a study of masculinity in contemporary film and television. Post-millennial masculinity is informed by several factors. Chief amongst these is the extraordinary visibility of queer sexuality, and of alternative and non-normative sexualities and gender identities, that inform the current moment. The genealogy of this visibility can be dated back to the early 1990s and the emergence of the term “queer” itself; once a term of homophobic abuse and now a re-appropriated rallying cry for a new kind of gay and lesbian identity that, to begin with, eschewed the terms “gay” and “lesbian” in favor of queer and its multivalent possibilities and affiliations. Masculinity of the present reflects the remarkable shifts in the gender and sexual domain; straight masculinity must now always proceed from the basis of an undeniable awareness of queer life, not only of its existence but also its open, energetic, heady display. Along with queer visibility, the rise of post-feminism (a decidedly ambiguous term) has radically reshaped conventional masculinity. Sex and the City-style female sexual consumerism has made men—male bodies in particular—sexual commodities, on constant display and ripe for delectation. The image of the heterosexual male both reflects market concerns and the wide-scale broadening of the desiring gaze. (Steven Soderberg’s 2012 male stripper movie Magic Mike and Steve McQueen’s Shame (2011), notable for its display of the full-frontal male nudity of its star Michael Fassbender in the early scenes, amply reflects the attention to both female and gay male audiences. Sadly, neither of these films is particularly good or progressive.)

I argue that film and television works have made the Male Face a metaphorical canvas for these shifts and their attendant anxieties. One particularly resonant image of masculinity recurs often in the films of the 2000s: a male face that has been rendered distorted or otherwise altered, that signifies either blank impenetrability or fiendish, mocking cruelty. The strange, uncanny, twisted, or denatured male face, indelibly figured in the first Scream (1996) film, prominently emblazons such films as Donnie Darko (Richard Kelly, 2001), with its protagonist’s encounter with both his own face and that of a nightmarish, leering rabbit-man; 25th Hour (Spike Lee, 2002), with its protagonist’s alternately triumphant and self-hectoring rant in the mirror, a sustained encounter between himself and his reflection; The 40 Year Old Virgin (Judd Apatow, 2005), with its climactic close-up of its protagonist, now triumphantly post-orgasmic (Steve Carell), right before he bursts into song (to celebrate the resolution of the narrative problem signaled by the title, he sings “The Age of Aquarius”; all of the other main male characters sing portions of the song as well in an extended musical sequence; Catherine Keener as the woman who ends the forty years of sexual solitude is notably absent from the singing, perhaps indicating that she has little reason to celebrate herself and that her main function has now been accomplished); Source Code (Duncan Jones, 2011), with a revelation that its protagonist is, in actuality, little more than just a face; Rob Zombie’s Halloween remake, aforementioned; Drive (Nicolas Winding Refn, 2011), which not only focuses intently on Ryan Gosling’s impassive but intensely intense facial expression but also tropes the idea of masculinity as a mask, literally representing the criminal protagonist, a stunt double among other occupations, wearing a mask, and not just for diegetically justified reasons; and Magic Mike, which figures its protagonist’s “turn” toward a moral and properly heterosexual life (i.e., a life in which he is no longer a male stripper for female audiences, and certainly not for gay male audiences, never shown in the film) through a sustained close-up of his face, his expression at once aghast and resolved. Television also makes use of the face as shifting symbol of masculinities, as I will attempt to show in a reading of the AMC series Breaking Bad (2008-present). What’s behind the face as a symbol for men? Especially when we consider that it is the woman’s face that, throughout film history, has been not only the cinematic face, but the figural representation of the cinema itself?1

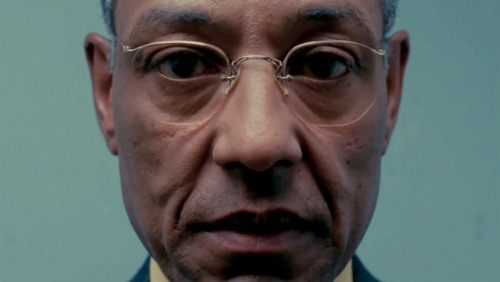

On Breaking Bad, created by Vince Gilligan, high school chemistry teacher Walter White (Bryan Cranston), having been diagnosed with advanced lung cancer, gets involved in the drug trade with a former student, Jesse Pinkman (Aaron Paul), ostensibly in order to ensure his family’s comfortable financial future. A chemistry genius, Walter creates an especially desirable and lucrative form of methamphetamine. A formidable villain introduced in the second season and dispatched in the fourth, Gustavo “Gus” Fring (Giancarlo Esposito) hides his drug-trade empire behind his establishment-identity as the owner of a successful chain of fried-chicken fast-food restaurants (Los Pollos Hermanos). Poised, polished, and extremely precise, Gus wears immaculate corporate-casual clothing at work and immaculate business suits when interviewed by increasingly suspicious detectives; he looks every inch the exemplary manager as he presides over his various stores, smiling in avuncular fashion at his ethnically diverse employees as he instructs them in chicken-frying techniques. The character, “a Chilean national,” would appear to represent a fading, Old World-South American gravitas and dignity. At the same time, the character is an emotional blank, able to stab one of his errant employees in the neck with unblinking, silent efficiency as Walter and Jesse gape in terror.

In the fourth season, however, Gus is humanized in an unexpected and jarring manner. Associated with nebulous crimes in his native country that make him notorious to those in the know, he emigrates to Mexico in 1989 and after that to the United States. Transplanted to the more colorfully explosive Mexico-drug-world, Gus and his South American gravitas stands out. Mexico is always contrasted in this matter against the region in which the series is principally set, the alternately suburban and desert-strewn Albuquerque, New Mexico. Gus emerges as an index of these loaded, potentially racist, certainly conventional regional and social distinctions. As a symbolic character, Gus seems meant to convey both racial-ethnic loss and mourning —the pains of immigration, assimilation, and self-made multicultural identity—and a new type of murderous menace, the ethnic killer dandy, a clinically neat, polished, murderous immigrant. (This type is analogous to the explosively violent black male intellectual, as I have discussed elsewhere.2 )

Exemplifying his conformance to a working-class-immigrant version of classic American self-made-man values, Gus’s taciturn, compact elegance comes to suggest a kind of wordless mourning over his cultural displacement. If his backstory evokes the trope of racial passing, what is interesting is the extent to which it also suggests a narrative of sexual passing. Though he frequently, in conversations with his employee Walter, talks about the importance of family, Gus is never shown with one. Gus emphasizes, in his rigid words about duty to one’s family, what a man must do. “What does a man do, Walter? A man provides. And he does it even when he’s not appreciated, or respected, or even loved. He simply bears up and he does it. Because he’s a man.”3

As his backstory reveals, Gus’s maintained his closest emotional tie to a young, gifted drug-maker he discovered and adopted in Chile; this young male protégé is killed, in a flashback scene, before Gus’s eyes during a meeting with a rival Mexican drug-kingpin named Don Eladio (played by Steven Bauer, who, not incidentally, played Al Pacino’s best friend in Brian De Palma’s 1983 film Scarface. Tony Montana ends up killing his best friend, the clearest sign that he has hit his lowest point). Gus is shown to be uncharacteristically devastated by the young man’s murder, which appears to motivate Gus’s serious turn to crime, violence, and vengeance. Don Eliado’s henchman, Héctor “Tio” Salamanca (Mark Margolis), a villain from a previous seasons, dispatches Gus’s “partner,” a word used here, I would argue, for its gay associations. Gus’s love for his young murdered partner doubles key aspects of the Walter-Jesse relationship, blurring the oedipal and the homoerotic.

To add to the homoerotic valences of Gus’s “back story,” Héctor pisses in a swimming pool before Don Eliado appears, and contemptuously—or flirtatiously?—sneers at Gus for “liking what he sees.” In the present action of the series, the aged, ruined Héctor, who cannot speak, reduced to wordless if rabid rage, sits in his wheelchair in a nursing home, able to move only one finger, which he uses to tap on a bell to signal his needs. He must endure endless visits from the now middle-aged Gus, who consistently tortures the old man with news of the assassinations, at Gus’s vengeful hand, of Héctor’s various family members.

Given the large number of thematic valences that attend his character—the possibilities of racial and sexual passing, the contrast between Old World and New, exemplified by Gus’s natty fashions in contrast to Walter’s plain, nondescript ones—the means of Gus’ expulsion from the narrative are just as interesting as every other aspect of his characterization. Working with the elderly drug-criminal Héctor, who once tried to have him and Jesse killed but who is more deeply Gus’s hated rival, Walter rigs it so that the Gus is blown up in the old man’s room in his nursing home. (The bomb is attached to the bell that the old man taps until the bomb explodes.) After the explosion, Gus walks with dignity through the swirling smoke. Standing outside the room, he readjusts his tie and regains his composure, as if the exploded bomb were a squirt of ketchup on his clothes. The camera pans from left to right—and when it does, we see the harrowing aftermath of the explosion on Gus. The right side of his face has been blown off, leaving only sinew and bone. Gus then collapses to his death. This episode, the last of season four, is aptly titled “Face-Off.” These instances of face-focused masculinity—no doubt film-goers and television viewers can cull several more, and I am not even referring here to the innumerable relevant males of the comic book genre, masked and otherwise—reveal something about the analogies genre film and television make between male personas, faces, and the senses of horror, violence, and ambivalence.

Image Credits:

1. Inter-generational styles of masculinity

2. Death’s Head Turtle

3. Gus Fring

4. Queer Gus

5. The Male Face

Please feel free to comment.

- First, we think of Gloria Swanson as Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard (Billy Wilder, 1950) championing the silent era of which she was a legendary star: “We didn’t need words—we had faces.” Clearly, it is Norma Desmond’s hypnotic face, in the film clips of her days as a young and lovely silent star and in her present hypnotic spectacle of theatrically defiant older age, that embodies the force of this line. Then there is the long, long close-up of Greta Garbo at the end of Queen Christina. One of the first film books I ever bought was called They Had Faces Then, a study of the classic Hollywood star. It focused exclusively on women’s faces. [↩]

- For an analysis of the figure of the violent black male intellectual, see Chapter 5, “The Seething Skin,” 97-117, in Greven, Gender and Sexuality in Star Trek: Allegories of Desire in the Television Series and Films (McFarland, 2009). [↩]

- Amanda Lotz discussed this scene as well in her insightful paper “We Must Be Outlaws: The Unbearable Burden of Straight White Men,” on what she calls the new cable television “male-centered drama,” given at the American Studies Association Annual Conference. San Juan, Puerto Rico, 2012. I was on this panel, “Mediating Masculine Hegemony in the Modern American Empire,” along with Lotz, Brenda Weber, and Anna Froula, who organized it. [↩]

I found Gus one of the most interesting characters on Breaking Bad, as he was most definitely a product of his environment, even more so than Jesse and Walter. The comparison of his young protege and he to Walter and Jesse mirrors the male-male relationship that the show has developed well over 5 season. I never thought about the fact that we saw Gus alone, cooking for himself, with no family. The link to Gus and homosexuality seems accurate when you look at Gus’ back story. Who would be that upset if it was just one of his employees. And he certainly wouldn’t have turned into the mass murderer that he became over an “employee”. The last shot of Gus before he dies is iconic. It leaves the viewer shocked, saddened, and uncertain of how to feel. As a viewer you want Gus to be dead and root for Walt and Jesse, but the character is so great, it’s hard to see him die. Especially at the hands of Salamanca.

Gus’ back story with his protege represents an alternate path that Walt could potentially go down if Jesse was murdered. Although Gus leaned more to Homosexual than Heterosexual his character is much more asexual than anything else. I believe one of the reasons the writers chose Gus to be this way is that they wanted Gus to be like no one else, a minority in every way. This made Gus unpredictable as a character, frightening, and interesting at the same time. But I do not believe that Gus or Walt and Jesse were influenced to greatly by post millennial masculinity. The mentor-protege relationship is one that has been around for thousands of years, along with it’s sometimes homosexual connotations. Even the character of Gus is not a new character, but the opposite, Gus is a character that you could find in a Hitchcock film, in fact he’s very similar to Uncle Charlie from Shadow of a Doubt.