What Should We Call Reading?

Mara Mills / New York University

I. Digital Decoding and Literacy

A reading environment of iPhone-books, text-to-speech, information retrieval, screened verbovisuals, prompt texts and textlinks demands its own theories of decoding and meaning-making. In I Read Where I Am, a compilation of “notes” by 82 artists, designers, and authors on human attention and intake in the “new information culture,” Anne Mangen (National Centre for Reading Research in Norway) defines digital reading as potentially multimodal, multimedial, and multisensory:

Reading has diffused to a virtually limitless variety of processes and practices with an equally endless variety of texts. How and to what extent are existing theories and models of reading able to explain what’s going on when we read the kinds of dynamic, interactive, ephemeral texts that appear and disappear in an instant, as in instant messaging and Twitter … Another challenge, hitherto unforeseen and hence largely neglected, is the role of the reading device itself … Reading should perhaps be reconceptualized as a multisensory engagement with a display of static and dynamic configurations, implemented in a device with particular sensorimotor, ergonomic, affordances which in different ways interact with perceptual cognitive processes at play.1

Reading has always been a roomy word, although even in Old English its definition was split between “decoding” and “interpretation.” Recent digital technologies provide new metaphors and means for theories of reading; neuroscientists have taken over the investigation of decoding, while literary and media scholars rethink interpretation. In the discourse of neuroscience, the activity of reading is miniaturized to a “chain of processing stages” that occur between the retina and the rest of the brain. As Stanislaus Dehaene explains in his definitive Reading in the Brain, the goal of research into the neural basis of reading over the past three decades has been “to crack the ‘algorithm’ of visual word recognition—the series of processing steps that a proficient reader applies to the problem of identifying written words.”2 The focus has thus been on print reading, refigured as a variety of machine reading.

In literary and media studies, many theorists have analyzed the “configuration” of human interpretative practices by digital media and machine reading protocols. Others, such as Katherine Hayles and Stephen Ramsay, argue for layered reading, with human interpretation extended through machinic aggregation or filtering.3 In either case, signal and interface transformations have encouraged new bodily habits and forms of attention related to reading: scanning, searching, linking, liking, clicking, selecting, cutting and pasting, navigating, sharing, skimming, looking, glancing, accessing, multitasking, mining, and pattern-recognizing. At a more abstract level, these techniques have suggested new interpretive modes: distracted, distant, shallow, surface, social, synthetic, collaborative, and hyper-reading.

Like the cognitive approach to decoding, there can be something functionalist about these new theories of interpretation, by which I mean that human behaviors are presented as functions of media affordances. Apart from social reading, many of these strategies are radically individualized, foregrounding a user and a personal device. In “How We Read,” Hayles recommends an expanded definition of reading, with a focus on proficient interpretation (i.e. literacy):

Literary studies teaches literacies across a range of media forms, including print and digital, and focuses on interpretation and analysis of patterns, meaning, and context through close, hyper, and machine reading practices. Reading has always been constituted through complex and diverse practices. Now it is time to rethink what reading is and how it works in the rich mixtures of words and images, sounds and animations, graphics and letters that constitute the environments of twenty-first century literacies.4

Still missing, as argued by Mangen, is a semiotics for multimedia, a way to join considerations of perception and interpretation. Also neglected by many of the literary models is the context of digital literacy itself, the question of reading-for. The “we” constituted through reading or implied by particular devices is another point of contention.

II. After Inkprint

Today’s crisis in the definition of reading was presaged in the last century by a similar set of debates about print access technologies and alternate reading formats for blind and print disabled people. As a result of the medium’s growing ubiquity and ties to the requirements of citizenship, exclusion from print began to be seen as disabling in and of itself. The notion of “print handicaps” became common in the library field after 1966, when Public Law 89-522 extended the Library of Congress Books for the Blind program to those with any impairment or cognitive difference who were “unable to read normal printed material.” Unlike dyslexia, medically defined as an impairment of the brain, the category of “print disability” focuses attention on the built environment (i.e. media) rather than physiology.

According to the neurotechnological paradigm, if the goal is fast and efficient reading, print may be essentially impairing. Dehaene writes, “Eye movements are the rate-limiting step in reading. If a full sentence is presented, word by word, at the precise point where the gaze is focalized, thus avoiding the need for eye movements, a good reader can read at staggering speed—a mean of eleven hundred words per minute.”5 He suggests a screening technique known as Rapid Serial Visual Presentation (RSVP) to inhibit the eye’s movements, or saccades, and he conjectures that “perhaps this computerized presentation mode represents the future of reading in a world where screens progressively replace paper. At any rate, as long as text is presented in pages and lines, acquisition through gaze will slow reading and impose an unavoidable limitation.”6

The modern literacy imperative in the United States prompted the development of dozens of new formats—aural, tactile, olfactory, visual— by which blind and other print disabled people could read. “Inkprint reading” became one among many possibilities, starting with raised print and Braille in the nineteenth century and joined in the twentieth by phonographic Talking Books, Radio Reading services, and a variety of electronic scanning devices for translating print into tones, Braille, vibrations, or speech. (One such scanning device is the Optacon, featured at the opening of this post.) Talking Books and Radio Reading are only available to readers with a medical certification of disability, hence I’ve classified them as “prescription media.” Formats like Braille were historically critiqued by sighted people for accentuating the differences between themselves and the blind—or for being “separatist” media. For many blind readers, on the other hand, Talking Books seem to embody a philosophy of normalization.

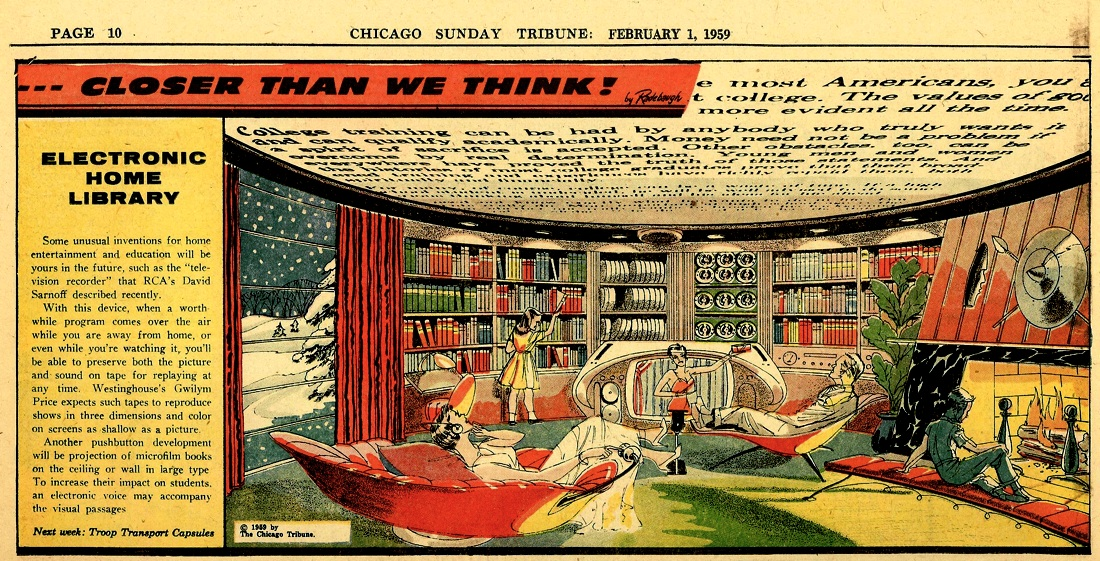

In some cases, these new formats were marketed to multiple audiences—an example of what Graham Pullin calls “resonant design”—connecting otherwise distinct groups through shared technical needs or enthusiasms.7 Libraries began loaning microfilm-based “ceiling book projectors” to so-called “bedfast” individuals in the 1940s. By the next decade, the high-tech family was also recruited into the imagined readership of projected books. Through accidental design convergences, artifacts with similar interfaces or outputs might also provoke resonances between seemingly dissimilar user groups; in a recent letter to the New York Times, disability theorist Rosemarie Garland-Thomson proposes that Autocorrect has destigmatized the idiosyncratic diction generated by speech recognition software.

Reading is an event that occurs between bodies, devices, symbols, and environments—if any of these vary, reading changes. Confronted with so many new reading formats, librarians, educators, and psychologists throughout the twentieth century began to revisit the old decoding-interpretation definition of reading (which in the U.S. had generally been elaborated to three stages: phonics or text-to-sound decoding, word comprehension, and interpretation). Was listening to audiobooks, for instance, reading or just an “aid to reading”? What of print decoded by Deaf readers, for whom phonics was irrelevant? Could Braille and tonal codes be considered “writing”? If speech itself was an encoded signal, how did it differ from writing?

These queries continue. In 2006, the National Accessible Reading Assessment Projects offered three definitions of reading, which successively decenter “writing” and “decoding”—but not “text”:8

Definition A

Reading is decoding and understanding written text. Decoding requires translating the symbols of writing systems (including braille) into the spoken words they represent. Understanding is determined by the purposes for reading, the context, the nature of the text, and the readers’ strategies and knowledge.Definition B

Reading is decoding and understanding text for particular reader purposes. Readers decode written text by translating text to speech, and translating directly to meaning. To understand written text, readers engage in constructive processes to make text meaningful, which is the end goal or product.Definition C

Reading is the process of deriving meaning from text. For the majority of readers, this process involves decoding written text. Some individuals require adaptations such as braille or auditorization to support the decoding process. Understanding text is determined by the purposes for reading, the context, the nature of the text, and the readers’ strategies and knowledge.

As reading becomes multimodal, it cannot be defined as a bodily function; it is rather a “sphere of activity” like play. Theories of digital reading must similarly grapple with the multiple formats for written text, the relationship of words to other signs, and the routes (whether neural or strategic) by which decoding occurs. As these theories evolve—following Garland-Thomson’s logic—perhaps “accessible reading” will no longer be set apart from reading per se.

III. On the Same Page

As a human invention, reading is necessarily social and political. In the schooling context, this goes without saying; accessible reading—like all reading—has long been tied to “discipline.” Literacy instruction poses “good reading” as purposeful and relatively coherent, an access-to something else (e.g. employment or the ”common culture” of a nation). As a mode of relation to objects and to other people, reading is not just benignly “communicative”: it can be exclusive, extractive, and enrolling; it can be unsettling or emulsifying. Although distinctions between print and electronic “cultures” are endemic to media studies (as in the claim that digital, networked technologies encourage remixing, multitasking, and interactivity) theories of digital reading have yet to adequately connect new readerly behaviors and modes of attention to questions of discipline and political economy.

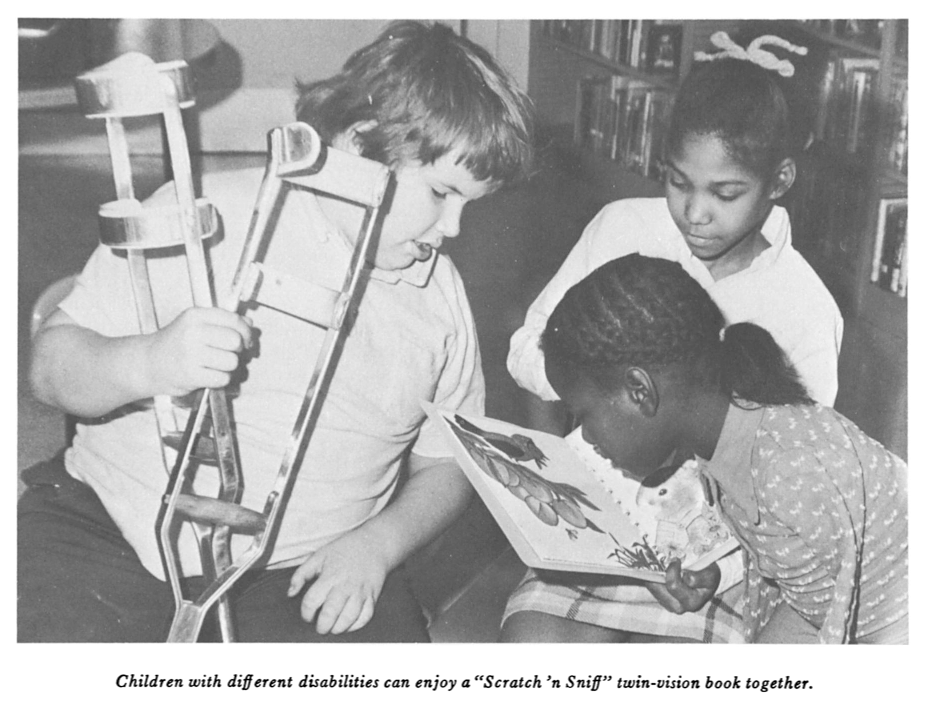

Studying “mediated congregation” in Protestant mega-churches, my colleague Erica Robles-Anderson asks of the screened—and often distributed—worship experience, “How do we know we’re on the same page?” For the case of digital reading, we might ask, “What does it mean to be on the same page?” Are “we” created, as an imagined community, through shared content across platforms, or through shared gestures and devices? This question can also be posed for low-tech multimodal reading formats, like the print/Braille/Scratch ‘n Sniff book pictured below. Designed with heterogeneous readers in mind, this device quite deliberately reformats reading—and also reading-together.9

From Catherine Wires, “Books for Children Who Read by Touch or Sound,”

The Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress 30, 2 (1973)

Image Credits:

1. Optacon text-to-tactile converter, c. 1964

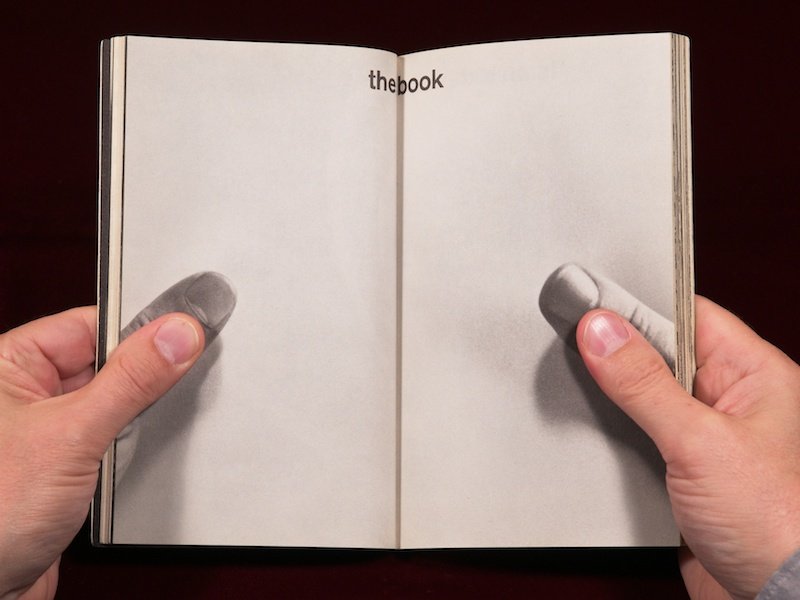

2. Configuring the Reader, from Marshall McLuhan’s The Medium is the Massage to the iPhone

3. “Ceiling Book Projector for Bed-ridden Patrons” of the East Baton Rouge Parish Public Library

4. “Electronic Home Library” Book Projector Accompanied by Electronic Voice

5. A visual-tactile-olfactory book. From Catherine Wires, “Books for Children Who Read by Touch or Sound,” The Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress 30, 2 (1973).

Please feel free to comment.

- Anne Mangen, “The Role of the Hardware,” in: I Read Where I Am, ed. Mieke Gerritzen, Geert Lovink and Minke Kampman (Amsterdam: Valiz, 2011), 106. For a brilliant series of explorations into the long history of “interacting with books,” see Andrew Piper’s Book Was There. [↩]

- Stanislaus Dehaene, Reading in the Brain: The Science and Evolution of a Human Invention (New York: Viking, 2009), 12. [↩]

- N. Katherine Hayles, How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012); Stephen Ramsay, Reading Machines: Toward an Algorithmic Criticism (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2011). [↩]

- Hayles, 78-9. In How We Think, Hayles provides an excellent summary of cognitive and humanistic approaches to digital reading, moreover she frames the latter in relation to a broad shift away from the “hermeneutics of suspicion” in literary theory. [↩]

- Dehaene, 17. [↩]

- Dehaene, 18. [↩]

- Graham Pullin, Design Meets Disability (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2009), 93. [↩]

- F. Cline, C. Johnstone, & T. King, Focus Group Reactions to Three Definitions of Reading (Minneapolis, MN: National Accessible Reading Assessment Projects, 2006). [↩]

- Combinations of print with Braille or raised lines were marketed, incongruously, as “twin vision” books. In the 1970s, contemporary examples of multimodal reading included touch-and-feel books as well as book-record and book-cassette combinations. [↩]

Pingback: People of the Book: Mara Mills | Ploughshares

Pingback: Chapter 1: “Homer’s Blind Bard” (TPE Endnotes) - There Plant Eyes