Habit-Change in the Mobile Present

Heidi Rae Cooley/ University of South Carolina

Camera Phone

With devices nearly always in hand, “on,” and connected, we have become increasingly accustomed to being on-grid and locatable. We rarely acknowledge the streams of data we proliferate on a daily basis. We disperse ourselves by means of texting, tweeting, picture-messaging, emailing; and we readily announce our location by these means. In the process, we fail to recognize our implication in a mode of governance that utilizes pervasive tracking in order to make the habits of populations predictable and thereby manageable. In response, I propose that we not only increase our awareness of how everyday media habits serve a biopolitical project of population management, but also begin to think of social change in terms of habit-change. In this way, we might formulate an alternative to liberalism’s framing of change as a problem of choice in the juridico-legal sense of “I have a right to choose.”

I am interested in recontextualizing the drive for pervasive registering of connections and exchanges through mobile media. In what follows, I outline how we might re-imagine the routine practices that, for example, litter Facebook “walls” and Twitter feeds with self-divulging updates and, consequently, render individual persons legible as an aggregate, as a population. I turn to Michel Foucault’s ethical living and Charles Sanders Peirce’s habit-change in order to propose a way to think about the possibility of changing habitual ways of being in the mobile present. By interweaving Foucault and Peirce, I offer a theoretical model for how populations might participate meaningfully in revising how they are managed as populations. Instead of radical or drastic action, I suggest an awareness that transpires on the cusp of consciousness, wherein the individual is both biologically calculable (Foucault) and cognitively expressive (Peirce). In doing so, I frame decision-making as a kind of responsiveness transpiring at the level of the individual person as organism, as part of the processes of cognition even as such processes are always informed by techniques of normation.

In the early 1980s, Foucault’s research emphasis shifted from questions of institutions, power, and architectures of truth to the problem of ethos, or practice of living.1 For him such living pursues a “politics of ourselves,” wherein a person’s style or manner of living cultivates a creative relation not only to herself but also to a population. In this way, it seeks to stimulate within a community of individuals a sensitivity to shared habits and tendencies as opposed to the shared deliberations emphasized by the liberal democratic notion of citizen-individuals. Ultimately, he suggests how such practices, or habits, morph in relation to a likewise ever-evolving context or, in his terms, milieu.

Foucault’s practice of artful living is one among a variety of theoretical calls for enacting a more ethical existence. American pragmatist Charles Sanders Peirce has a contribution to make to this discussion. While known in media studies circles primarily for his semiology, Pierce also developed a notion of habit-change that allows us to recast in pragmatic terms of Foucault’s aesthetics of existence.2 For Peirce, our ways of knowing, which materialize our ways of being, are shared collectively through semiosis. Semiosis is an ongoing process of meaning-making that transpires as cognition at the level of the organism. According to Peirce, we make sense of things within a “circle of society.”3 Meanings cohere only because of collective habits; they are “binding” across a community–a population. They imply “ethical solidarity.”4 In fact, ethics lays at the center of what it means to think, act, believe–or more fundamentally, be. Moreover, Peirce aligns ethics with aesthetics, which manifests as “a sort of intellectual sympathy.”5

Because Pierce sees ethics as a semiotic process, he can specify ethos more concretely than Foucault. For him, it’s about changing the interpretant. Here, it’s worth recalling the triadic character of the Peircean sign. A sign may be iconic, bearing a resemblance to that which it represents (e.g., a portrait); it may be indexical, physically connected to or pointing to some that-has-been or this-is-happening (e.g., a weather vane); it may be symbolic, heeding arbitrary rules that govern interpretation (e.g., the word “stop”). Additionally, a sign may be any combination of these, as in the case of a photograph, which is both iconic and indexical–and symbolic if, for example, signage appears in-frame. The moment we make a connection between a sign and its meaning is the moment of the interpretant: My phone vibrates, I recognize it as an incoming message.

Tweeting, texting, and sharing images via MMS and social-networking platforms are new habits a large number of us have acquired. To suggest habit-change is not to argue against these activities or the pleasures we derive from them. Rather, it is to propose that we strive for a sensitivity to, i.e., a “sense” of, the shared habits we routinely enact such that we might engage them differently. In the mobile present this might mean inhabiting location awareness: My phone vibrates, I recognize it as an incoming message. But…I might also immediately think to myself, “Yes, I’m on-grid”–even as I poise myself to reply. In other words, habit-change is subtle. It does not seek to accomplish the kind of radical change that protests and political rallies intend. And as a living aesthesis, i.e., sensory knowing, it is not committed to the kinds of interventionist art works that Mimi Sheller discusses in her column “Mobile Mediality”. If Peircean habit-change succeeds, it will be because it produces new habits, not because it promotes any explicit challenge to the mainstream. And this is where its value lays.

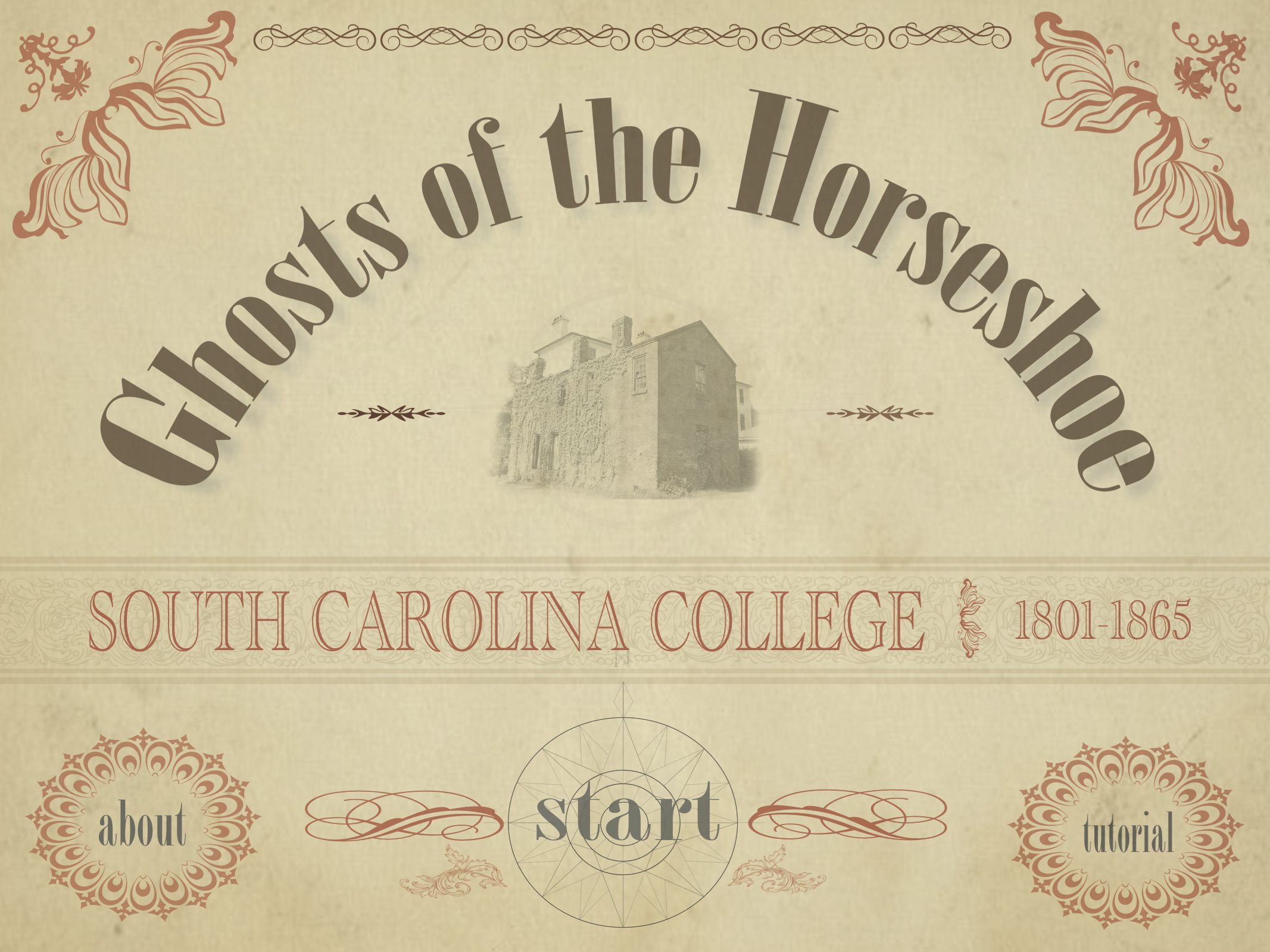

Ghosts of the Horseshoe Splash Page

Ghosts of the Horseshoe ArchoWheel

In the subsequent installments, I present two distinct examples of how habit-change might be elicited. The first example is an Augmented Reality [AR] application for iPad. Called Ghosts of the Horseshoe, the application seeks to encourage students of and visitors to the historic Horseshoe of the University of South Carolina to “see” and experience, as tangible, a usually unacknowledged institutional history.6 Using AR overlays, the project endeavors to elicit an awareness of slavery as materially fundamental to establishing, building, and maintaining South Carolina College, USC’s original antebellum campus. The second example is an iPhone application called Augusta App.7 By means of QR-codes, GPS-mapping, Twitter-like feeds and updates, and semantic visualization, the app engages participants in questions of tracking, locatability, and findability. It does so in order to draw attention to everyday processes that register individuals in relation to a broader community–in this case, the application’s community of participants.

Augusta App QR Code

Image Credits:

1. Camera Phone (Author’s image)

2. Ghosts of the Horseshoe splash screen. (Design: Brian Harmon, in consultation with students enrolled in “ Critical Interactives.”)

3. Example of Ghosts’ user interface indicating theme and years defining interaction. (Design: Ian O’Briant, in consultation with students enrolled in “Critical Interactives.”)

4. QR-code. (Credit: Duncan Buell)

Please feel free to comment.

- See: Michel Foucault, “On the Genealogy of Ethics: An Overview of Work in Progress,” The Essential Works of Foucault, 1954-1984, ed. Paul Rabinow (New York: New Press, 1997), Michel Foucault, “About the Beginning of the Hermeneutics of the Self. Two Lectures at Dartmouth,” Political Theory 21.2 (May 1993). [↩]

- In my book-length project, I read Peirce in tandem with biophilosopher Henri Bergson and neurophysiologist Antonio Damasio in order explain how industrial design keeps devices in-hand and, as such, facilitates tracking but also affords new habits of self-expression (texts, tweets, mobile imaging thumbnails). I explain that neurophysiology and the biophilosophy of Bergson help us to understand this at the level of the organism–which is also where we begin to think about habit-formation as Peirce theorizes it. [↩]

- Charles S. Peirce, Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, ed. Charles Hartshorne and Paul Weiss, vol. 5 (Cambridge,: Harvard University Press, 1934) 281 [5.421]. [↩]

- Karl-Otto Apel, Charles S. Peirce: From Pragmatism to Pragmaticism, trans. John Michale Krois (New York: Humanity Books, 1995) 92. [↩]

- Peirce, Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce 73 [5.113]. [↩]

- Ghosts of the Horseshoe is currently being developed by graduate and undergraduate students enrolled in “Critical Interactives” (Fall 2012), a cross-College course that I am team-teaching with computer scientist Dr. Duncan Buell. Students: George Akhvlediani (computer science), Andrew Ball (computer science), Bryan Brewton (film and media studies), Chase Daigle (computer science), Renaldo Doe (computer science), Itamar Friedman (history of technology), Brian Harmon (composition and rhetoric), Mike Hughes (media arts), Olivia Keyes (film and media studies), Geoff Marsi (computer science), Amanda Noll (public history), Ian O’Bryant (media arts), Jessica Tompkins (media arts), and Richard Walker (computer science). [↩]

- Augusta App, currently under development, is a digital supplement to my book project. I thank my design team Duncan Buell, artist Simon Tarr and computer science undergraduate student Jeremy Greenberger. [↩]

Pingback: Habit-Change in the Mobile Present II: Ghosts of the Horseshoe and Remembering History Otherwise Heidi Rae Cooley/ University of South Carolina | Flow