Blind Spots: Religion in Media Studies

Erica Robles-Anderson / New York University

For several years I have worked at the intersection of media, architecture, and religion. In other words, I study churches. This is not exactly a popular area for academic research. My colleagues, mostly secular humanists like myself, often do not see the appeal. And I confess, I did not come to churches for religion. I came for the media. Today, hundreds upon hundreds of churches have sanctuaries that feature state-of-the-art sound and lighting systems, projection, high-definition, and plasma screens. Worshippers gather by the thousands in buildings that look more like strip malls, office complexes, big box stores, or auditoriums than they do like sacred spaces. Mobile devices are Bibles and congregational life extends through online networked space. In other words, church no longer looks like church.

Connecting with a higher power in hyper-mediated conditions somehow seems uncanny. Churches, at least in the popular imagination, are atmospheres of quietude and communion. They are supposed to clearly mark the distinction between the sacred and everyday, aren’t they? More than six million Americans worship in spectacularly large, high-tech churches. The material culture of religion has profoundly changed.1 Understanding just how Protestantism came to be re-imagined in a new technological regime has not convinced me that the boundaries between mythic and mundane have blurred. Rather, I have come to believe that there is something of a blind spot in our analytical vision. Protestantism has always been a media project and religion is central to the project of social theory.

Martin Luther may have nailed theses to the door, but Gutenberg’s invention brought down the cathedral, or so thought Victor Hugo.2 As a critique of priestly indulgences and papal authority, the Reformation was a theological position and social movement well-suited to the mechanical reproduction of the written word. The rise of print capitalism in Early Modern Europe guaranteed that methods for translation and dissemination could carry both sacred texts and Luther’s trenchant words far beyond Wittenberg, Germany. The concomitant rise of reading publics demonstrated that Biblical knowledge could flow in the vernacular, independent from priestly interpreters of Latin anointed by the Roman Catholic Church.

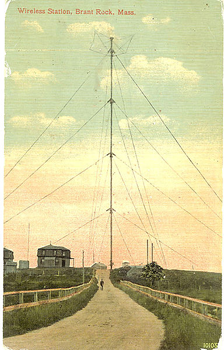

So too, the birth of electronic media bears traces of interlocking spiritual and technical aims. The first words transmitted by telegraph were “What hath God wrought?”, a reference from the Book of Numbers.3 Telegraphs were nicknamed “lightning lines,” a reference to the Book of Job.4 Voice broadcasting began on Christmas Eve in 1906. From the Brant Rock Tower on the Massachusetts coastline, Reginald Fessenden read from the Book of Luke.5 Evangelists were among the first on radio, television, cable, satellite, and Internet. To the student of media history, these religious contributions should come as no surprise. Electronic media have always held the promise of bringing a vast distribution of individuals into a common fold. This is mediated congregation.

Yet one would be hard-pressed to argue that religion is more than a peripheral concern. Embedded in social theory is a notion that by 1910 everything had changed. Media, communication and transportation technologies rearranged time and space so profoundly that traditional world views fell away; modernization rent the spiritual from the social. Therefore, scholars interested in understanding the logics of social life are more likely to attend to structures emblematic of modernity like markets, spheres, nations, and now networks, than those forms of collective life dependent upon communion and intersubjectivity. Although the Bible is still the most widely produced book, the connections between cosmology and technology have become very hard to see. Hyper-mediated churches seem anathema. Even scholarly reports of religious media are dominated by a “gee whiz, Christians use Facebook!” or “what would Jesus SMS?” sensibility that seems to reconfirm a status difference between religion and modernity. The approach seems somehow like Creationism which cedes to the methods of science the project of faith.

Further compounding the distortion in our analytic lens is an over-narrow focus on Protestantism. To see the consequences of this constraining, one need only to slightly shift the gaze. Consider the case of the bootleg benedictions. It is said that in his final days Pope John Paul II would offer blessings from his balcony to the waiting crowds below. Bootleggers recorded these appearances and later sold the video tapes to believers that wanted to receive blessings on demand. Not surprisingly, the Vatican denounced these black market benedictions. Within the Catholic faith papal blessings travel only through proper channels: diocese, yes; television, no. Mechanical reproduction strips the sacred power from the gesture. Walter Benjamin might well appreciate the Vatican’s position. In fact, a whole set of media theorists might. From Walter Ong, who drew our attention to the technologizing of the word, to Marshall McLuhan, who insisted that the medium is the message, to Bruno Latour, who argues that actors in networks translate and that we have never been modern, a crucial question about the status of mediation emerges. It is perhaps no coincidence that all share a Catholic cosmology in which intercessors play a crucial theological and institutional role. Protestantism carries no such baggage.

When asked, “Why study churches?”, I no longer answer by presenting religiosity through technology as a curiosity in a secular age. We can no more think about what sustains the social order in technological regimes without religious studies than we can without media studies. Reformation was a paradoxical kind of project. It is a media history of the unmediated.

Protestantism rejected the Catholic insistence on spiritual intercessors and simultaneously entwined with media channels that could transmit, broadcast, or transfer the faith. Conversions can happen in churches or in fields, in the presence of clergy or laity. The gospel can be transmitted via book or Internet, television broadcast or mobile telephone. Ironically it is a blind spot that makes Protestantism so adaptable to diverse technological and material conditions. The medium is decidedly not the message. In fact, it cannot be. As media theorists, however, we would do well to attend to the diverse forms of social life that similarly rely on the possibility for unmediated, untranslated, direct connection. We just might find that even the most technocratic regimes are sustained by spiritual ambitions.

Image Credits:

1. Lakewood Church in Houston, Texas

2. Brant Rock Radio Tower circa 1910

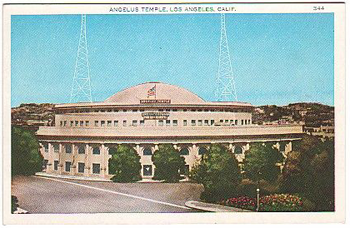

3. Angelus Temple in Los Angeles, California

Please feel free to comment.

- More than 1600 “megachurches” have been documented in the United State alone. Megachurches are defined as those Protestant churches with more than 2000 attendees at Sunday services. The Hartford Institute for Religion Research maintains an online database of megachurches here. [↩]

- Victor Hugo (1917). This will destroy that, in Notre Dame de Paris. Harvard Classics Shelf of Fiction, accessible here. [↩]

- Numbers 23:23 KJV [↩]

- Job 37:3 KJV [↩]

- Fessenden interrupted the normal dots and dashes of wireless telegraphy for a special broadcast that played on Christmas Eve and then again on New Year’s Eve. Fessenden played an Edison recording of Handel’s Largo, then O Holy Night on violin, and then read Luke 2:9-14. A re-enactment of Fessenden’s broadcast can be heard here. [↩]

and more importantly, your personal experienceMindfully using our emotions as data about our inner state and knowing when it’s better to de-escalate by taking a time out are great tools. Appreciate you reading and sharing your story, since I can certainly relate and I think others can too

Oooh.

I could see how expanding on:

1. the definitions of

“technology’ (and their inter-relation to other definitional contexts, [as Relevant])”

being employed here

And then

2. The relevancy of

“the medium is the message”

Could further the dialogue.

Idk if building this thought into something book length with popular tangibility is a center of personal concern or relevance,

But I just stumbled into this as a know-nothing on whatever you consider relevant intellectual canon to it,

and selfishly, I prefer consuming and studying media made available to read or listen to as a book, terrible habit.

Thanks for the read.