Defanged: The Curious Case of the Family-Friendly Vampire

Andrew Scahill / George Mason University

Vampires are defined, in part, by their lack of aging, their superhuman bloodlust, and their perverse sexuality. Children are defined, in part, by their continuing development, their vulnerability, and their complete lack of sexuality. What, then, do we make of the vampire child?

In the last decade, a number of horror texts have taken advantage of this dissonance by crafting childlike terrors that, by virtue of their monstrosity, trouble the definition of childhood. Vampire children like Homer in Near Dark, Claudia in Interview with a Vampire, or Eli in Let the Right One In evidence deep-seated contradictions as they violate the defining characteristics of childlike bodies: dependency, vulnerability, innocence, and futurity.

In children’s media, magic has long held a central place within the medium (Harry Potter, The Wizards of Waverly Place), and the child-as-extraterrestrial (Escape from Witch Mountain, Animorphs, Ben10) recurs frequently to allegorize the child’s literal alienation within the greater adult world. But outside of the horror genre, the child-as-vampire remains a rarity due to the extreme narrative acrobatics it requires. What can we learn by examining how the incompatible becomes accommodated? How, indeed, does one “defang” a vampire and make it palatable for a conservative family-friendly viewership?

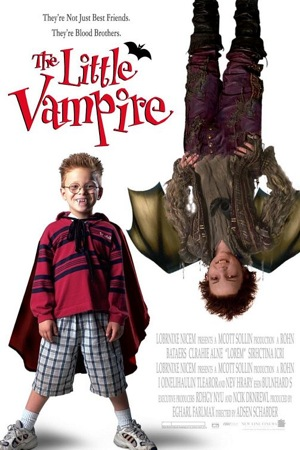

The Little Vampire (2000) enjoys annual rebroadcast every Halloween on ABC Family and the Disney Channel. In the family comedy, an American boy named Tony moves to a Scottish village with his mother and father. After being bullied, Tony befriends a vampire boy named Rudolf and is adopted by Rudolf’s “family,” consisting of a mother, father, and three vampire children. Tony and his family then work to protect the undead from a Van Helsing-like vampire hunter and magically restore them to the ranks of the living.

The Little Vampire arrives at a curious modern place within the vampire mythology, as texts increasingly centralize the vampire as a figure of sympathetic identification. In what I call the “domestication of the vampire,” texts such as Twilight (2009), The Vampire Chronicles and even True Blood promote a breed of vampires that exist within, rather than simply in opposition to, notions of the familial. As a conservative Mormon fable, Twilight’s Edward proves his “goodness,” in part, by maintaining a system of blood relations that diffuses the queerness of vampire kinship. In Twilight, the “good vampires” play all-American baseball and maintain what they call a “forever family.” The text’s hero also refuses to drink human blood, or even have sex before marriage—a wholesome vampire if ever there was one. The vampire, once a hyperbolized symbol of sexual perversity, becomes in Twilight a wan metaphor for teenage angst and chaste uncorrupted longing.

In order to make the vampires the unproblematic heroes of The Little Vampire, the film likewise has its vampires favor alternatives to human blood, feeding on cattle. When Tony first encounters vampire boy Rudolf, he aids him in finding a cow upon which to feed. Now indebted to Tony, Rudolf takes Tony out flying—demonstrating the wondrous nature of his vampirism that allows Tony to escape the humdrum reality of his human life. “As long as I’m holding on to you, you’re fine,” says Rudolf. “Trust me.” One expects that their path takes them to the “second star to the right, straight on till midnight,” as their magical evening so echoes the narrative of J.M. Barrie’s and Disney’s Peter Pan. Indeed, this use of Peter Pan one of many ways in which the film diffuses the problematic or transgressive qualities of the vampire mythos by recombining it with adult fantasies of childhood.

Further, the film normalizes the vampires by reconfiguring the origin narrative. In this film, vampirism is the result of an ancient curse rather than being “turned” or converted by an existing vampire. As Peter Pan softens the child vampire’s mix of innocence and experience, The Little Vampire uses the fairy tale Pinocchio, also a popular Disney property, to imbue Rudolf with a sympathetic Otherness. In this reworked mythology, the vampire family has strove for centuries to restore themselves to proper humanity. This quest is particularly central for Rudolf, who has wished all of his life to become (like Pinocchio) “a real boy” and live in the sunlight. “We want to become humans, not eat them for dinner,” explains Rudolf. Part Peter Pan, part Pinocchio, young Rudolf is cast as an eternally innocent child cursed by ill fate but whose humanity will be granted when he has proven himself worthy.

Unlike Pinocchio, however, Rudolf’s journey to becoming a real boy does not occur as an individual act of self-discovery. Rather, as a “family-friendly” film, The Little Vampire elevates kinship ties to an essential character, where magic can occur only through the cooperation of parents and children. When Rudolf returns to his domestic catacomb, his mother and father pull him tight and plant kisses on his forehead. Soon the entire family are reunited in familial bliss. “We’re family, not fiends,” says young Rudolf—a phrase that could represent the film’s ideology as a whole. As in Twilight, heterosexual kinship relations stand as irrefutable evidence of normalcy, and therefore, humanity. John D’Emilio notes that the family, as a symbolic, can be used “as both a symbol and a weapon. As a symbol, it harkens back to an imaginary past when everything was fine, good, and orderly. As a weapon, it divides society into good people and bad people, the moral and the immoral, the productive citizen and the social parasite.”1 This domestication of the vampire on the side of heterosexual kinship stands in direct opposition to the perversity of the vampire system of relations, in which family members are selected based on sexual lust and polymorphous desire (as used by Anne Rice and Poppy Z. Brite to highlight the queerness of the vampire mythology).2

To complete this realignment of the vampire mythos with a conservative worldview that aligns nonfamilial relations with perversity, the film utilizes signifiers of queerness to code the film’s resident Van Helsing—here called Rookery—as the film’s antagonist. “Rookery” is an interesting choice for the character, as this is British slang for a dangerous slum, and also the site wherein Charles Dickens placed many of his young boy protagonists in peril. Befitting his name, Rookery is unkempt and wanders the country roads at night with his male companion looking to destroy cadres of vampire families. A modern-day Fagin, Rookery demonstrates a markedly unnatural interest in young Rudolf and Tony, drawing upon the incendiary link between homosexuality and pedophilia. Indeed, he seems opposed to all things familial and heterosexual: as his male companion laments, “No family, no one to be with… Just me and these dead people.” In Rookery’s overwrought mission to destroy vampires (he is stuck in the past), he has neglected the cultural signposts of sexual normalcy: heterosexual courtship and the formation of a family. He is paradoxically positioned as the avatar of sexual perversion and anti-futurity3 against the sexual normalcy and heterosexual kinship bonds presented by the vampire family. In evacuating sexual perversity from the figure of the vampire in favor of heteronormativity, the mythology is not only defanged, but defaged.

The film reaches its climax when Tony locates the magical amulet that restores the vampires to their former human form. Holding the amulet to a passing comet and wishing for their humanity (“When you wish upon a star…,” as the Pinocchio song goes), the vampires evaporate. In the film’s denouement, as Tony and his parents prepare to leave Scotland, a new family moves into their old home—a family which bears a striking similarity to the vampires recently granted humanity. Recognizing each other, the families embrace as the credits roll. It is readily apparent in the epilogue that the families are meant to double each other as the former vampires, now restored to their true status take the place of Tony’s blood family. Where they began as inverse objects, Tony and Rudolf now stand as consummate doppelgangers: Tony gaining Rudolf’s strength to defeat his bullies, Rudolf adopting Tony’s playfulness and childlike wonder. Now dressed in kid-appropriate attire, the once-vampire Rudolf and his sister seem unencumbered by the centuries of existence that would deem them defacto adults. Rather, we are to understand that their exterior now matches their interior—mentally, emotionally, they were always children, never corrupted by experience. This is the last in a series of narrative evacuations and additions that allow the vampire child—swathed in Disney fairy tales and the impossibility of childhood innocence—to exist within a conservative ethos.

Image Credits:

1. Poster for The Little Vampire

2. Flying in The Little Vampire, Author’s Screencap

3. Flying in Peter Pan

4. Pinocchio becomes a real boy

5. The Little Vampire‘s “normal family”, Author’s Screencap

6. Rookery from The Little Vampire, Author’s Screencap

7. Family restored in The Little Vampire, Author’s Screencap

Please feel free to comment.

- Don D’Emilio, The World Turned: Essays on Gay History, Politics, and Culture. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2003. 179. [↩]

- Additionally, Ellis Hanson writes at length on the longstanding homophobic rhetoric that links queerness with vampirism, renewed particularly during the AIDS crisis. As he notes, the queer became associated with tainted blood, pathogen and contagion, and the predatory vampire that lured unwitting innocents into its perverse ranks. See Ellis Hanson, “The Undead.” inside/out: Lesbian Theories, Gay Theories. ed. Diana Fuss. New York: Routledge, 1991. 324-340. [↩]

- For more on the connection between queerness and anti-futurity, see Lee Edelman, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004. [↩]

The “Incendiary link between homosexuality and pedophilia” sounds pretty fucking homophobic. Gay people aren’t pedophiles. The LGBT+ community do not accept pedophiles as part of the community because pedophilia is fucking wrong. How dare you insinuate that there is a direct link between being gay and being a pedophile. Sounds like a pretty backward rhetoric for a time so modern as today. And insinuating that heterosexual romances and kinship is “normal” is pretty fucking bonkers, homosexual relationships show up in every animal within the animal kingdom, and you want to know what humans are? animals. Also you’re using the word Incendiary wrong.