How We Talk About Media Refusal, Part 3: Aesthetics

Laura Portwood-Stacer / New York University

People decide to abstain from engaging with certain media or media platforms for many reasons. My previous two Flow posts explored two motivations often invoked within discourses of media refusal: addiction and asceticism. People may consciously avoid using a particular form of media because they fear their current consumption practices are becoming pathological (the addiction frame) or they feel their lives and selves can be improved through non-consumption (the asceticism frame). A third justification is also sometimes offered by media refusers, which we might call the aesthetic frame.

Aesthetic justifications for media refusal are all over the place. Neil Young hates the MP3 format because he says it compromises sound quality. That’s an aesthetic argument – it relies on a shared belief among Young and other “audiophiles” that more sonic information equals a qualitatively better media consumption experience. Plenty of people refuse to see films based on books they love, because they think the movie can’t measure up to the quality of the book. In the realm of social media platforms, many former Myspace users claimed to have stopped using the site because its interface just got too ugly.1 These are all examples of individuals refusing some form of media for aesthetic reasons.

Refusal and taste

Aesthetic justifications for media refusal are seemingly simple, because they rely on the idea of taste, which is generally understood to be deeply personal and unmotivated. In other words, we tend to feel like having a preference or distaste for an object is something which cannot be helped—it seems to be beyond reason or alteration, and we certainly don’t intend to favor one thing over another out of malice or prejudice. But, as Pierre Bourdieu’s influential sociological work on taste has argued, aesthetic preferences are not as “innocent” as they seem. According to Bourdieu, preferences which feel deeply subjective are in fact structured by social background and the routines of everyday life these backgrounds impart to us (what Bourdieu termed the “habitus”). Tastes thus emerge in patterned ways among social groups, and, as a consequence, are expressive of already existing social stratifications. The perpetuation of these stratifications is masked, however, by the fact that the “aesthetic sense” is felt to be natural, given its cultivation over long periods of time and its reflection in the tastes of one’s closest peers. That’s precisely why taste is so effective at perpetuating social hierarchies in a supposedly egalitarian society—having “discriminating tastes” doesn’t feel like actual discrimination. It’s a free country, and everyone gets to make their own choices about what to consume, right?

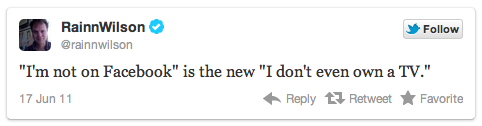

I speculate that refusing to engage with a particular medium on the basis of aesthetics may in fact be an implicit (and even unconscious) performance of taste and status, a kind of “conspicuous non-consumption” (to invoke an idea I developed in a different context).2 Statements like “I don’t even own a TV” rub some people the wrong way precisely because they seem to indict the tastes of those who do enjoy watching television. Even if that’s not what the TV refuser intended, the underlying reification of taste hierarchies is what makes their aesthetic preference seem so hipstery and off-putting. It’s a variation of the “I liked X before it was cool” meme: “I stopped using Y before everyone else stopped using it.”

The aesthetic disposition

Let’s back up a bit and think about what it means that people even offer aesthetic justifications for refusal of media consumption. In Distinction, Bourdieu’s tome on taste and aesthetic preferences, he notes that the “aesthetic disposition” is only available to people who are assured that their “material needs” will be met. He means by this that people only begin to differentiate among things based on aesthetic values when the material functions of these objects are inconsequential. To take a basic example, a starving person does not reject a particular food because she prefers the taste of a different food. Another individual who is assured she will be well fed in any case can afford to introduce aesthetic distinctions into her selection (and rejection) process. Bourdieu, drawing on Marx, called this kind of expression of aesthetic preference the “asceticism of the privileged” which is unique to “the bourgeois experience of the world,” and may be especially common among intellectuals and artists who lack economic means but still wish to assert their cultural capital.

But what would it mean to have one’s “material needs” met in the realm of media consumption? Clearly, “material” and “needs” will have to be more loosely defined than if we are talking about food used to nourish the body. But media consumption does serve important practical purposes in many societies. It facilitates communication between family members, friends, and even business associates. Anecdotally, I’ve found that being well versed in the latest happenings on American Idol has been a great help in social interactions where I might not have much else in common with my conversation partners, particularly across lines of age and educational background. As someone with a doctorate in media studies, an aesthetic critique of American Idol would certainly be easy for me to make, but to reject the show on these terms could foreclose opportunities for making ties across social strata, particularly with those who do not share my educational “privilege.” This is a reductive example, but it points to the value of exploring the potential social effects of practices of media refusal.

It’s also worth thinking about how the aesthetic motivations for refusal go hand in hand with processes of technological innovation and cross-platform migrations of media content (topics explored by Michael Z. Newman and Elana Levine in their recent book Legitimating Television). Why, for example, do some people who “don’t even own a TV” readily admit to liking HBO shows and desiring the ability to access HBO’s television content online without actually having to subscribe to cable? Surely there are multiple factors at work here, some to do with the varying practicalities of technological formats, but some also to do with discourses of “quality television” and, yes, taste hierarchies. Examples like this also illustrate that refusal is closely related to the adoption of alternatives. It’s rarely the case that consumption and communication are wholly rejected; rather, people are seeking arenas for these cultural practices that best fit within their larger set of values and routines. Studying practices and discourses of media refusal can thus shed light on what these values and routines are.

Overall, it’s clear that motivations and justifications for media refusal are numerous and complex. We need to explore them further!

Image Credits:

1. Neil Young, Aesthetics, and the Detestable mp3

2. Rainn Wilson’s Tweet – Author screen shot.

3. Ariel’s Viewing Preferences

Please feel free to comment.

- This case was fascinatingly documented by both danah boyd and S. Craig Watkins. Boyd further developed her analysis in the essay “White Flight in Networked Publics,” in Lisa Nakamura and Peter Chow-White’s book Race After the Internet. Whitney Erin Boesel has also recently written thoughtful analyses of related phenomena. [↩]

- I also develop this concept further within the context of users’ rejection of Facebook, in a longer piece, entitled “Media Refusal and Conspicuous Non-Consumption: The Performative and Political Dimensions of Facebook Abstention” (New Media & Society, forthcoming). [↩]

It is becoming increasingly frequent that technology users are faced with a new form of social media and are presented with alternative means of interacting with existing or new online communities. Refusing to participate in forms of media due to aesthetic frame seems to have two faces. One, as in the case of Neil Young and the MP3 format, can be justified as the medium was explored, evaluated, and simply did not suit needs on a basis of performance quality. Naturally, with any product, if it doesn’t work or doesn’t evoke quality in its intended function, consumers aren’t likely to continue using it. The other face of aesthetically framed media refusal fueled by taste and status does not seem to hold proper justification. However, because social stratifications are instilled and often subconscious, this face is likely unavoidable as well. Some people find a sense of self-empowerment or pride in their refusal to give in to trends or fads. This includes involvement in new social media. For instance, I found myself apprehensive to make the switch from MySpace to Facebook in 2008 because of my feelings of resistance toward anything trending or new. This is especially the case if you find yourself unable to identify with the media platform’s current users. As suggested by the term itself, media refusal may not give a fair chance to upcoming media platforms. However, it is probable that this idea will remain unavoidable as there is always someone itching to stray from the crowd.

You aptly use Bourdieu’s distinction to analyze media refusal. Perhaps the most common example for many Flow readers lies in how academic departments and faculty within those departments utilize media refusal in a way that reveals their cultural and social “location.” I taught for many years in English departments, where faculty frequently were proud not to own a TV, to ration their children’s media consumption severely, and, for many years, did not know how to send or receive attachments (this last problem has disappeared with a younger generation of profs).

The most recent phenomenon in this regard has been academics’ frequent refusal of ebooks, but even that has given way as literature lovers and their families give each other Kindles for gifts or have bought iPads for children. Since Bourdieu considers taste in terms of “class fractions,” it is useful to consider how certain formats—such as blu-ray DVDs—enter into the market now as appealing to our own class fraction—that of media scholars. And as frequent as ebook refusal is among academics, the opposite is also true: many of us are frequent purchasers of ebooks.

In this light, pay special attention to holiday shopping this year, and also observe it in those around you: how many academic families will have an e-reader or iPad under the tree? Even with the easily proclaimed refusal of ebooks among academics, I suspect that we are one of the main targets for ebook/ereader marketing.

Thanks for your comments, Sarah and Julia. Good points to consider!

Every day, we are bombarded with new media, and as the author has pointed out, we do not choose to participate in all of it. There are only so many profiles and sites we can successfully keep track of with only 24 hours in the day. In my own experiences, I’ve noticed that involvement in social media does not necessarily have to do with our tastes or the aesthetics of a site, but often our need for social acceptance and participation. The author notes that she watches American Idol, not because she singularly enjoys it, but to be included in the social conversation surrounding that piece of media. Similarly, we choose which social media sites to become involved in based on our peers. These days, not being on Facebook or Twitter is seen as a form of backwardness and results in social isolation, both online and offline. Therefore, our choice to become involved on Facebook, Twitter and other social media sites is often ultimately decided for us, despite our aesthetic tastes.

Laura,

I found your paragraph on material needs in media consumption, particularly with regards to television and HBO shows (for example) very interesting. More and more often, I hear the sentences such as, “I don’t have a TV because I don’t need a TV to watch TV Shows,” or “why would I listen to a radio if I can hear what I want to on Pandora?” When someone makes such a comment, the “taste hierarchies” that you describe come to light.

On the topic of refusal and taste, one wonders if aesthetics start to play a role in websites that are visited frequently. In fact, when thinking about aesthetics and media refusal, my mind went instantly to Facebook and Myspace. Myspace, with all its abilities to change layouts, add music and implode pages with images and difficult-to-read text was quickly overshadowed by the much simpler, easier-to-navigate Facebook. In looking as social media now, structure and consistency significantly supersede an ability to customize. Rather than wanting the ability to change the way our “pages” look, as was done in Xanga, Myspace and Blogger, the trend is to now limit the customization of these websites. Perhaps this is because people has simply become disinterested in creating visually appealing pages that focus on their individuality?

Social interests are constantly changing. This is partially due to the amount of new media technologies and information we are provided on a regular basis. It is hard to keep up with everything because people have different routines and lifestyles. This article really hit the nail on the head with how preferences come from social groups, and further than that I think the way we use new media is also influence by social groups. Being a college student on a budget, I am guilty of not owning cable. Unfortunately, I do still have a TV, but that is another story. I share a netflix account with one of my friends, and without that I wouldn’t keep up with many shows or movies. I also find myself watching shows online either on websites that friends send me, or shows that they send me information about. If I didn’t have friends encouraging me to watch tv on my laptop, I probably would splurge for cable. It is true that I continue to watch these shows not only because I enjoy them, but also for a common interest with my friends. It is easier to have more to talk about with more people than feeling out of the loop. The same would be true if trying to power down from Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, etc. Many conversations with my friends revolve around “this post on facebook” “this persons event” “that persons new pictures” etc. Not keeping myself frequently logged into these sites really keeps me a few steps behind. In college, the easiest way to keep up is with a smartphone. Without it, my routine would not permit me to stay up to date by any means.

Laura, some more thoughts and an important resource for you. Since the arrival of digital video and digital film storage via DVD, experimental filmmakers have debated film versus DVD for years on a listserv, Frameworks, for which all of the entries are archived and available online. Every possible consideration from the filmmakers’ perspective has been raised there across the years as film stocks declined and digital video improved. You can trace much media refusal here on the part of independent filmmakers, for aesthetic reasons. Sadly, in the process of this media refusal, a great treasure of experimental film has been lost, when it could have been preserved digitally–and perhaps still could be. If you wrote about this phenomenon, you would be taking up an important chapter in contemporary film history. Interestingly, the filmmakers are very articulate, and the Frameworks archives documents it all.

Once again, I praise you for this project, since media refusal is so much a part of our social and personal history, and the dimensions of that media refusal, both on a personal and more large scale level, change over time.

Laura, thank you for posting up this series. The section on aesthetic disposition really made me think about my media consumption. When choosing media platforms, I feel that (in my personal experience) aesthetics plays a bigger role than the actual functionality. I agree that material needs should be met first before aesthetics, but I find that I am satisfied with the bare minimum at times. For example, many of my peers rely on Reddit for entertainment purposes and view other sites as “not good enough.” However, I follow another lesser known site because it has a cleaner interface and easier to navigate. I understand that Reddit has more features and is essentially “better” than the site I choose to follow, but my site still does its job. In my case, I feel that my tastes are more “innocent,” in the sense that there is virtually no influence from my social background nor my everyday routines. In regards to this article, I assume that my “material needs” are just different from those of my peers.

At what point is it a matter of selection (connoisseurship) rather than refusal? Last night I thought “there’s nothing on TV” (actually a rather large package of Direct TV channels) nor was there “anything” appealing on the DVR. I turned to Netflix, and there were 350 titles pre-selected by my spouse. After browsing 50, I went grazing on my own, and after a bit settled on a Brit TV series I’d never seen (ITV’s 1991 Prime Suspect). So I actively “refused” about 150 items before settling on something.

I’ve just been offered access to a Cloud-based music server with “30 Million” songs.

I agree with applying Bourdieu’s Distinction analysis to media choice. But I’m not sure that the term refusal actually works very well in many cases. As some previous commentators note, economics, lifestyle, and practical matters intervene in consumption decisions. The precise location of my home, and the limited service in my hometown means I really couldn’t use a 4G network at this point except when I travel to a larger urban area. Am I really “refusing” that smartphone choice? Or is the market “refusing” me?

Julia – thank you for this fantastic suggestion. I have been looking for examples of just such discourse as you describe happening on the Frameworks listserv. I’ll definitely check it out!

Sally – thanks for sharing your experience, it’s interesting!

Chuck – you bring up great points that are important to consider in refining the definition of “refusal.” I like your use of “connoisseurship” to capture the simultaneous embrace of one medium or text and rejection of others. The issue of access is crucial as well. One thing that I’d like to think about is the presumption that all users would embrace a technology or medium if only they had the access. So in your case, I would say that dominant media discourse presumes that you would love to join a 4G network if only your area had access to it. I’m curious whether cases of active refusal (where physical access is already in place) might force us to question such assumptions, and in turn to rethink the idea that media consumption is a universal value. As you say, refusal doesn’t apply to all (or even most) cases of media non-use, but I’m hoping it proves to be a revealing framework in some cases at least.

Pingback: Navigating Social Media as an Emerging Media Studies Academic « jonescene

Thanks for your comments, Sarah and Julia. Good points to consider!

http://www.photocanvas.in.th/ << Aesthetical art on canvas

Thank!! very much for your new media and as the author has pointed out.

Wow Thanks for your comments, Good points to consider!

Nice Share Very Nice It Good Over Mind สอน photoshop

Nice Pic Nice Comment Is Very Good I Like This Website ^^

เที่ยวเมืองเลย

Nice Share Very Nice It Good Over Mind

Sally – thanks for sharing your experience, it’s interesting!

Chuck – you bring up great points that are important to consider in refining the definition of “refusal.” I like your use of “connoisseurship” to capture the simultaneous embrace of one medium or text and rejection of others. The issue of access is crucial as well. One thing that I’d like to think about is the presumption that all users would embrace a technology or medium if only they had the access. So in your case, I would say that dominant media discourse presumes that you would love to join a 4G network if only your area had access to it. I’m curious whether cases of active refusal (where physical access is already in place) might force us to question such assumptions, and in turn to rethink the idea that media consumption is a universal value. As you say, refusal doesn’t apply to all (or even most) cases of media non-use, but I’m hoping it proves to be a revealing framework in some cases at least.

Thank you very much for such a great and useful article.

I feel like it has expanded my knowledge.

I also find this article creative and inspiring.

Thank You Nice Idea and Good ຂ່າວ

Thanks fo rsharıng

title in their work before they chase their remedies against pensioners and students, years after anyone who could verify ownership has passed!

want to demonstrate for more state power, yet lament about the tactics of the police.

@Michael: Support the Libertarians, if there are any in the UK.

Pingback: Media Aesthetics: Sensory or Societal? | Coding & Decoding

Pingback: Face away from Facebook! | quinny nguyen

In Response to media. Majority believes on what they see rather than what they read. I can’t blame this people who actually read the whole story and doesn’t satisfy to what they saw. The movie is just a summary to the story, it doesn’t have to be a very detailed manner, it will takes bloody ages to finish the whole movie if we put it that way.

The point is we only care about what the story is all about then we can jump into the conclusion. Cheers!

Mp3 is just a smallest compression rate for audio quality, when we say smallest, it means that it’s not as good or better than the original ones, even higher bitrate is far from the original quality. If you want a topnotch quality then better buy the original cd rather than goofing the web complaining things. Mp3 is only used to share to the people who can’t even afford to buy the original disc.

Thanks for your comments, Sarah and Julia. Good points to consider!

sexar6