Comedy and the Social Contract: The Surprisingly Conservative Vision of Louis C.K.

Carrie Andersen / FLOW Marketing Editor

On stand-up comedian Louis C.K.’s widely acclaimed television show, Louie, a woman plucks a strawberry from Louie’s breakfast plate while he dines at a restaurant. She asks in passing (and without waiting for a response), “Can I have one of these? Thanks!” Most people would chalk this strawberry loss up to bad luck and grumble about the woman’s presumptuousness. But Louie replies: “No, you can’t.” She is baffled by his retort, having already eaten the strawberry. He ends the exchange by pointing out the ridiculousness of her request: “You asked me if you could have one, and I said no, so… you just ate a strawberry that you can’t have.” As we see, Louie continually grapples with rules that govern human behavior in his usually unpleasant encounters with others.

Beyond the strawberry issue, Louie explores lofty questions that half-hour comedy programs rarely confront. How do we live a good life? How do we cultivate a code of conduct for our world? How can we avoid being awful to each other?

C.K. is no stranger to questions of living an ethical life—and, aware of his moral choices, often puts his own behavior on trial. In his December 2011 stand-up special, Live at Beacon Theater, the comedian describes one of his own falls from grace.

Too late for a flight to return his rental car, C.K. simply drives the car to the terminal—not to the rental car return—and boards his flight. He then calls Hertz to explain where the car is, and the employee exasperatedly explains the proper rental return procedure. C.K. replies matter-of-factly, “Well, I didn’t do that already, and now I’m leaving California.” Hertz sends an employee to retrieve the car, and C.K. avoids any consequences from his failure to abide by the rules.

Although C.K. realizes he could do this every time he flies to avoid Hertz’s bureaucratic song and dance, he knows it is wrong. Considering the broader consequences of this behavior, Louis advises, “You should act in a way, that if everyone acted that way, things would work out. Because it would be mayhem if everyone was like that.” This is Louis C.K.’s crude twist on Immanuel Kant’s categorical imperative: for Kant, a principle (or, in his words, a maxim) is ethical if it would “become through your will a universal law of nature.”1

C.K.’s maxim is, of course, not a strict reinterpretation of Kant’s. Louis is concerned with the outcome of his actions—he wants “things to work out”—while Kant questions whether we act in alignment with what duty requires of us. But both evaluate ethical choices based on the negative criterion of universalizability: you can’t make exceptions for yourself even if you want to.

Louis’s consequentialism also makes him more concerned with how actions can help society function as painlessly as possible. Unfortunately, he has a dim view of how this works in practice. C.K.’s crafted world in Louie becomes an arena in which moral quandaries about our world are tested and diagnosed through a character based almost entirely upon C.K. himself. And C.K. is more than simply a player: his personal sensibilities and philosophies innervate the core of the show, as he is its sole writer, director, and, until its third season, editor.

The deepest flaws that plague Louie’s world are found in the institutions intended to educate and cultivate moral character. We see weaknesses in the school system, for example, when a PTA meeting devolves into a battle among almost hyperbolically unpleasant parents and no headway is made to address real problems:

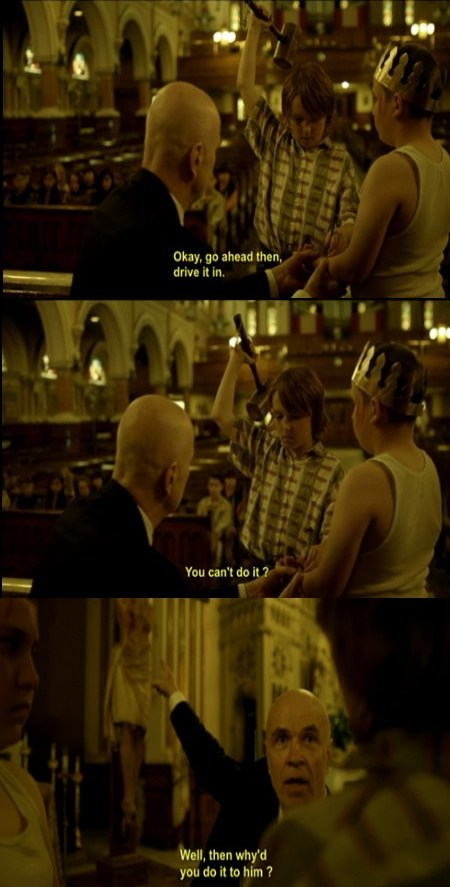

Similarly, the church is concerned with punishing sin over encouraging compassion for one’s neighbors. As a child, Louie was prodded to literally drive nails through his friend because, as a sinner, he was so willing to do the same to Jesus, leaving him mired in a perpetual state of apostasy as an adult:

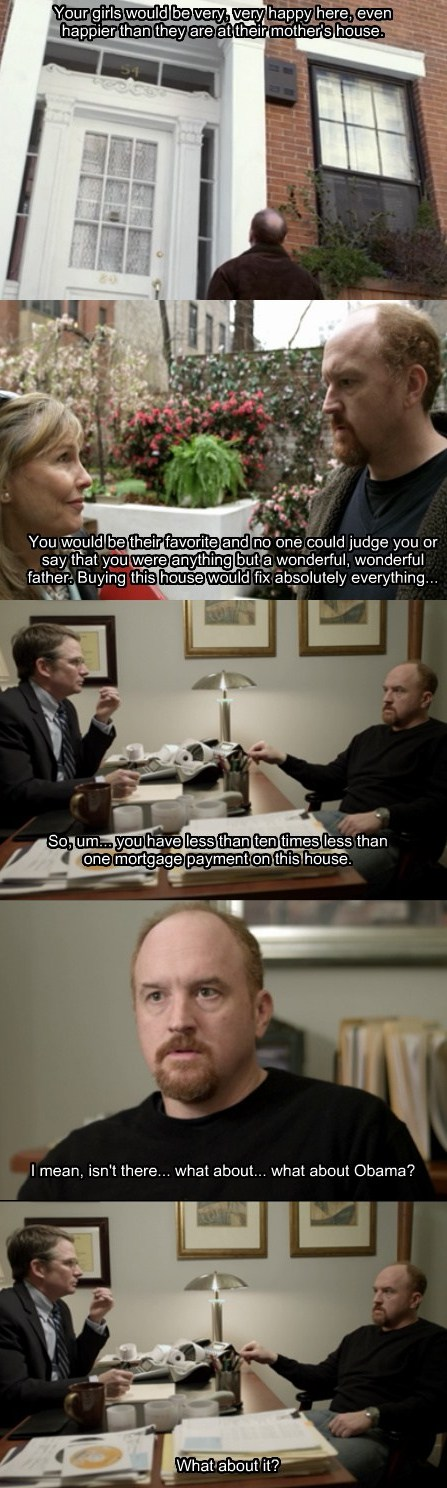

The government, even with Obama at the helm, cannot provide Louie the support he expects. Louie hopes to buy a $17 million home for his daughters, imagining that an upgrade in housing will heal the familial wounds opened from his divorce and reconfigure him as a good father. His accountant, however, advises him that his $7,000 in savings are not quite enough for this purchase, prompting a Hail Mary pass to our Commander-in-Chief:

The senselessness of these institutions means Louie has little incentive to participate in them. Nor does he have any possibility of benefiting from them. He cannot rely on any formal organization for moral uplift. Louie must rely on himself and incidental human decency.

Louie’s lack of faith in formal institutions parallels a trend in late 20th century American life that Robert Putnam has explored for the past twenty years. Putnam’s work points to declines in membership in voluntary associations of several kinds since the 1960s, which he suggests may underlie other destructive trends: declines in social trust, civic engagement, and norms of reciprocity.2

But the sociological concern with social obligation and withering ties is much older than Putnam’s research. Alexis de Tocqueville’s canonical exploration of American life and temperament at our nation’s inception similarly advocates the voluntary association (or, for political theorist Edmund Burke, “little platoons” of civic life) like Louie’s PTA.3 Likewise, Tocqueville reminds us that the individualist spirit that inheres in a democratic society can result in the atrophy of civic life as it also encourages closing one’s social sphere to those close to him. He warns, “Individualism…disposes each citizen to isolate himself from the mass of his fellow men and to draw himself off to the side with his family and his friends in such a way that…he willingly abandons the larger society to itself.”4 Both Putnam and Tocqueville worry that the ties that bind us in mutual obligation may be limited to those close to us, rather than extended to a broad civic community.

In a world like Louie’s where the system is both flawed and nonsensical, and where institutions cannot provide moral guidance or community, maybe focusing on the family is the best he (and we) can do. Louie is not bent on fixing the institutions that fail him. He embarks on no quest to right the wrongs of the Catholic Church. He doesn’t return to another PTA meeting. Instead, he turns to his relationships and casual encounters with others. Just like Voltaire’s Candide, Louie’s energies rest primarily in cultivating his own tiny, immediate garden.

Louie clings to the idea that we owe goodness to each other. One of the most extraordinary moments in the show’s second season occurs on the subway, where he notices a pool of sludge on a seat. His fellow passengers look on with disgust, making no moves to clean the mess. But Louie does what he feels is right: he sacrifices a clean shirt to wipe the sludge away, bathing in the gratitude of his onlookers until he snaps to his senses. His action was a mere fantasy of compassion. The sludge remains:

But although Louie hopes for a broad social contract that encourages such actions, the bulk of his efforts to live a good life focus narrowly on his family. Louie’s duty to instill moral values in his daughters is featured throughout the show, but he nonetheless remains ambivalent about this charge.

Louie knows that his daughters rescue him from moral declension. After dropping the girls off to stay with their mother for a week, he proclaims, “I’m not going to be a bag of shit like I always am,” briefly vowing to engage in healthy behavior. However much our behaviors are driven by unconscious or external forces, we want to believe that we are on our own and in control, as philosophy scholar Firman DeBrabander points out. We don’t want to believe that, rather than living, “we are lived.”5

Nonetheless, he immediately succumbs to his Id. In a grossly sexualized display of physical appetite, Louie plows through an entire pint of ice cream in a few brief moments:

But he also detests this parental obligation. Just before he devours his ice cream, Louie laments, “Every day that you spend with your kids is torture.” Louie—like many of us—is tempted by his animal desires. He longs to give in to his selfishness, to be completely self-contained. He wants to toss his daughters aside so he can eat pint after pint guilt-free.

This impulse is not surprising. After all, radical self-reliance is appealing in an age when we cannot rely upon formal institutions for guidance. Believing that we could survive on our own is empowering.6 But the independence that Louie idealizes is far from the self-interest rightly understood that Tocqueville lauds. We do not “sacrifice [ourselves] to [our] fellow man.”7 Giving up our clothes to mop up a mess on a subway car is only a fantasy. The reality is, Louie points out, that we’re assholes. Although we want to believe we’d do the right thing, left to our own devices, we would give the middle finger to those who count on us so we can eat junk until we pass out.

Against these urges that he himself finds grotesque, Louie yearns for mutual obligation and a fixed social contract within a disorderly, fragmented world that lacks institutional support. These are surprisingly conservative ideals that contrast with C.K.’s otherwise progressive repute. I don’t mean that C.K. endorses Mitt Romney or Tea Party politics. Nor do I believe that Louie should be read as a solely conservative text: one of the show’s best attributes is its moral complexity and its progressive vision of what we owe each other. But these hopes for constancy and broad moral social codes that require us to conquer our reptilian brains resemble paleoconservative political and moral philosophies of thinkers like Russell Kirk.

Kirk was speaking of individuals like Louie when he asserted that “man is a creature fallen from grace.”8 It’s in our nature to gulp down the ice cream. But our purpose on this planet, he argues, is ultimately to reject these desires as best we can, “to struggle, to suffer, to contend against the evil that is in [our] neighbors and in [us], and to aspire toward the triumph of Love.”9 In Kirk’s Old Testament mind, an orderly and just society is possible if we first learn to love particular individuals: our families, associates, communities.10 As ambivalent as he is, if Louie learns to avoid base temptations with the help of (and for the sake of) his daughters, he might have a shot at living in a decent world.

Should we be surprised that these moral fibers run so strongly through a cable comedy program? I don’t think so. Comedy has a long history of offering social critique and suggesting how we should act. And perhaps delivering hard truths obliquely through comedy is more effective than a political jeremiad. Maybe the message to shape up for the good of society is more palatable from Louis C.K. than it is from Jimmy Carter, whose reproaching malaise speech, while initially well-received for asking Americans to make personal sacrifices for the benefit of the nation, soon gave way to Reagan’s rosy rebuttal: “I find no national malaise, I find nothing wrong with the American people.”11

No sacrifice necessary in our shining city upon a hill. At least, not as long as we can simply take a strawberry that we can’t or shouldn’t have. Louie invites us to take a hard look at ourselves in the mirror, recognize our excess, our failings, our repugnant shortcomings, and learn how we might move towards the light of common decency and individual responsibility.

Image Credits:

1. Louie’s experience with the Catholic Church (author’s screen capture).

2. Louie’s dashed home-ownership hopes (author’s screen capture).

3. Top: Louie dives into the ice cream. Bottom: the aftermath (author’s screen capture).

Please feel free to comment.

- Immanuel Kant, Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals (New Haven: Yale University Press), 38. [↩]

- Robert Putnam, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2000). [↩]

- Thomas E. Woods, Jr., “Defending the ‘Little Platoons’; Communitarianism in American Conservatism,” American Studies 40, no. 3 (1999): 127-145. [↩]

- Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 2000), 205. [↩]

- Firman DeBrabander, “Deluded Individualism,” New York Times, August 18, 2012, accessed August 25, 2012, http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/08/18/deluded-individualism/. [↩]

- This flavor of empowerment also underlies the appeal of festivals like Burning Man, an “annual art event and temporary community based on radical self-expression and self-reliance in the Black Rock Desert of Nevada.” [↩]

- Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 220. [↩]

- Russell Kirk, “Conservatism, Liberalism, Fraternity,” lecture given in June 1954 to Chi Omega, in The Chi Omega Address, 1914-1954 (1956), 115. [↩]

- Kirk, “Conservatism, Liberalism, Fraternity,” 115. [↩]

- Kirk, “Conservatism, Liberalism, Fraternity,” 116. Kirk’s understanding of the moral uplift that can arise from immediate and particular human relationships draws in part from Tocqueville and Edmund Burke, who similarly believed that specific relationships are more likely to foster love and justice than more abstract sentiments about others. See Barbara J. Elliott’s “Faith, Civil Society, and the American Founding” on The Imaginative Conservative for a thoughtful exploration of how these conservatives imagine community in America. [↩]

- Ronald Reagan, “A Vision for America,” November 3, 1980, accessed August 6, 2012, http://www.reagan.utexas.edu/archives/reference/11.3.80.html. [↩]

This is a really smart article about someone who will be regarded as a very significant figure for our times, much like thinking about Woody Allen’s cinema in the 1970s. Really well done!

I really enjoyed this article and appreciate that you point to both progressive and conservative themes and struggles in Louie. Other interesting things to explore morally when watching this show and several others are tensions between expressions of entitlement and insecurity. Obviously when our relationship and interactions with other people resume themselves greatly to institutional arrangements how can we be moved to genuine empathy and responsability toward each other?

Randy – thanks for the kind words! Louis and Woody Allen converge in other ways these days… Susan Morse, the editor for Louie‘s third season, was Allen’s chief editor from Manhattan until the 1990s. So if you see any similar stylistic threads between the two, I’d guess it’s Morse’s doing (aside from the NYC centric nature of their narratives, but that’s a whole other story). And look for C.K. in Allen’s next movie…

Claire – thanks so much. One of the things that I love about Louie is its moral density: there’s so much to dissect in terms of how the show imagines human relationships alone, let alone broader political constructs. Your comment on empathy reminds me of a moment in the third season where C.K. and Parker Posey help a homeless man – exploring the politics and the empathy in that interaction alone would require so much more discussion!

Pingback: H II Regions, 30 August 2012 « Cosmic Vinegar

Pingback: Grad Research: Carrie Andersen Writes on Louis C.K.’s Conservative Vision « AMS :: ATX

This is a fantastic article Carrie. I think it’s interesting how Louis wrestles with his inner desire to be selfish and neglect his duties as a father and a productive human. You expertly pointed out how he wishes he was a better member of society, his fantasy of cleaning up the mess in the subway, but falls short like most of us would/do in that situation. With that said, you point out that he shows constraint when eating ice cream as not be seen as a poor example of a dad to his daughters. I can relate to his pseudo-conservitism, which can be read as a form of practical living rather than a political viewpoint. In the universe that Louis has created in his show he has managed to show the complex nature of the absurdity of our world.

This is an awesome article and an awesome show! I agree with Randy that Louie will be remembered much as Woody Allen is. I love that Louie has a poster of Lenny Bruce on his wall.

Towards the end of your article you mention that “…perhaps delivering hard truths obliquely through comedy is more effective than a political jeremiad”. I think that this is especially obvious with the success of the Daily Show. But it also reminds me of what Frank Zappa represented in the 1980’s. Zappa used humor to deliver harsh truths as well. He referred to himself as a “practical conservative” and showed the same loss of faith in moral institutions that Louie does. This loss of faith was typified by his opposition to censorship and in turn, an opposition to the government and church as moral shepherds: “…where institutions cannot provide moral guidance or community, maybe focusing on the family is the best he (and we) can do”. Be this a political ideal or not, I completely agree with it. The value of family and individuality over institutions and community is nothing novel. The balance between self-preservation and civic responsibility is prominent in American myth and culture. I believe Louie’s position is that altruism is ultimately a selfish act, shown through his fantasy of recognition on the subway and his intrinsic concern for self-preservation throughout the show. Many of his hilarious yet harsh points reveal the animalistic side of human nature, “…But our purpose on this planet, he argues, is ultimately to reject these desires as best we can, “to struggle, to suffer, to contend against the evil that is in [our] neighbors and in [us], and to aspire toward the triumph of Love” (Kirk).

However I think Louie deviates from Russel Kirk’s end goal of the “triumph of love”. A scene from Louie comes to mind in which his pot smoking neighbor, embracing his freedom, impulsively drops a water jug from his high rise flat onto a parked car. Other strange things happen which alienate Louie from his neighbor. He is perplexed, as he often is, by people’s actions. Similar to this reference is Frank Zappa’s voiced opposition against the counterculture ideals of the 1960’s and 1970’s with songs such as “Oh No” (1970):

“Oh no I don’t believe it, you say that you think you know the meaning of love

Do you really think it can be told? You say that you really know

I think you should check it again

How can you say what you believe will be the key to a world of love?

All your love – Will it save me? All your love – Will it save the world from what we can’t understand?

Oh no I don’t believe it”

You say that “Although we want to believe we’d do the right thing, left to our own devices, we would give the middle finger to those who count on us so we can eat junk until we pass out.” I think this is ultimately Louie’s point. Any aspiration towards the “triumph of love” is left to the institutions, illustrated by say the masturbation episode, in which Louie simultaneously addresses media absurdity and the naïve benevolence of religious followers. In that episode Louie’s moral nemesis seeks a moment of true love, while Louie is racing for the next flatulent, masturbatory release (as detailed by Louie’s “cum and farts” rant). So in the end, “Louie must rely on himself and incidental human decency.”

Great points in this article.

Reading it I was reminded of two particular instances in the show: One where Louie talks about a time when his cousin from a small town came to New York for the first time. She saw a homeless person for the first time in her life and tried to help him, whereas Louie tried to prevent her from doing so, telling her that “we don’t do that here”. (“Here” being New York) He tells this story in a way that puts his, and our, apathy in the spotlight, but the story, hauntingly, has no end. The homeless person is not helped, the society goes on and the kind cousin is dragged away from the homeless person by Louie. It’s really interesting to me that Louie does not show human decency in this instant and doesn’t, arguably, “do the right thing”. He merely makes us realize the impossibility of the “right thing” as long as one is involved in our contemporary society and holds a mirror to us.

Another instance is when Louie’s destitute friend Eddie comes to town, telling Louie that he’s going to kill himself. Louie spends the entire night with him but realizes that he’s risking his sanity by doing all this. He recedes from the responsibility to his friend, citing that he now has two daughters that depend on him. It’s an interesting development because it’s as if that instead of our responsibilities to fellow human beings increasing as we get older, there is this notion that, no, we cannot care about our suicidal friends like we used to when we have kids. Our responsibilities are closer to our vest, smaller but deeper.

These complex moral attitudes of Louie is what elevates his sentimental outlook on life above the “Love conquers all” and “We should be decent to other human beings!”. In one key episode, a Duckling that escapes from inside Louie’s pocket prevents an all-out shooting and yet it’s not the love between the Duckling and Louie or anything sentimental like that… It just happens that Louie looks ridiculously funny trying to catch a duckling. The opposing sides don’t come to an understanding or engage in a moral argument, it’s just, for a moment there, life is too funny to shoot someone else.

Pingback: Stream Blog