Surveillance and Disinformation

Hacked: Nadia El Fani’s “Bedwin Hacker”

Dale Hudson / NYU Abu Dhabi

Within digitized and networked forms of contemporary globalization, technologies regulate immigration and information according to regimes of virtual labor recruitment, examined in “Race and Labor, Unplugged: Alex Rivera’s Sleep Dealer,” and virtual border control, examined in “Biometrics and Machinima, Reanimated: Jacqueline Goss’s Stranger Comes to Town.” Film- and video-makers analyze these technologies for their antidemocratic perils, sometimes pointing to ways that these technologies can be jammed or even hacked towards democratic potentials. Nadia El Fani’s Bedwin Hacker (Tunisia-France-Morocco 2002) challenges assumptions about postcolonial migrations as unequivocal threats to the lives of law-abiding state citizens in the former colonial métropoles by defining congruencies between discourses that malign immigration as a degenerative form of cultural invasion or submersion and discourses that malign hacking as a destructive form of vandalism against intellectual property or terrorism against the state. These discourses become mobilized in the film when highly stylized, two-dimensional, animated images of a camel interrupt television broadcasts to proclaim a “new epoch” and affirm: “bedwin is not a mirage”.

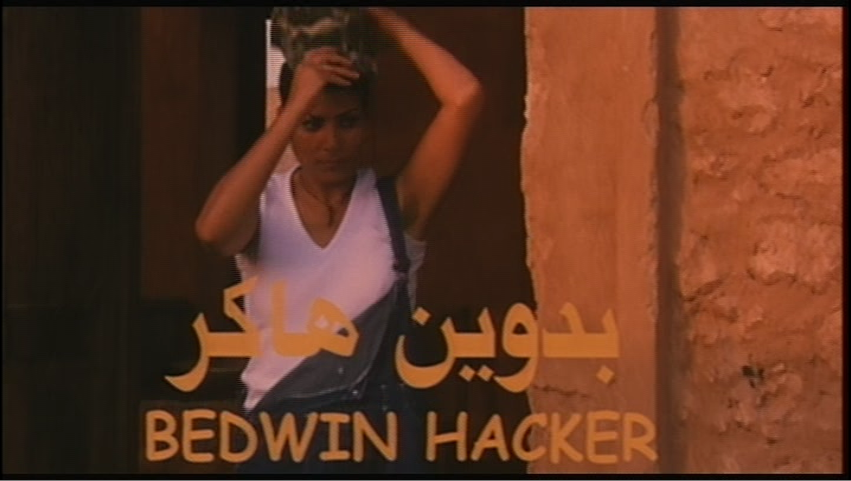

The film’s title introduces misunderstood and often maligned categories—“Bedouin nomads” and “computer hackers”—interrogated by the image of the film’s protagonist who appears behind the title in Arabic and French (image 1). Kathoum “Kalt” (Sonia Hamza) is a Tunisian computer programmer educated at the prestigious École Polytechnique in Paris. Her appearance, behavior, and intelligence refuse to conform to expectations on either the French and Tunisian side of the Mediterranean. The title’s challenge is multilingual and multilayered in an ever-adapting unfolding of different recombinations of Arabic and French dialects and of data and metadata. If verlan came to define a critical mass of films by French Maghrébis in “le cinéma beur” (beur cinema) as a form of slang from the streets of Paris and Marseilles, then Bedwin Hacker looks to a transnational cyber slang that uses keystroke-saving phonetic substitutions to point to larger frames of reference.1 Moreover, if the identity formation of beur attempted to reject a monolithic notion of French identity and empower the most “visible” minority in France only to be commercialized into a depoliticized “beur, blanc, et black” (beur, white, and “black”), then bedwin might possibly transcend the notion of national identity altogether.2 The term might encourage transnational understandings and thereby empower the “invisible” majorities in France and Tunisia, as well as elsewhere—everyone, citizen and foreigner alike, the multitude—in ways that escape the surveillance of racialization and the disinformation of imagined threats to actual racial and religious equality.

Perhaps more at the time of its release a decade ago than today, the film disrupts assumptions about digital literacy, political activism, and the role of women in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) based upon misinformation distributed by foreign media, particularly for audiences illiterate in Arabic before the launch of Al Jazeera English in 2006.3 Bedwin Hacker confronts the powers of state disinformation that contribute to the persistence of cultural misassumptions, such as the MENA is fundamentally “backwards” and hacking is invariably “criminal,” that converge on the bodies of women in new and enduring forms of surveillance and disinformation. The connection between jamming private satellites and protesting anti-immigration laws is announced in the film’s opening sequences that establish the digital proximity of physically distant and divided spaces. Images of a camel, clothed and doing a split, appear on television screens (images 2-4), are followed by scenes of a musical protest (“non, à exclusion”) by the Association Sans Papiers in Paris, then by images of the Saharan dunes in Tunisia, so as to suggest ways that digital domains might be mobilized to liberate physical spaces.

Surveillance and disinformation take place in physical and virtual spaces. Early in the film, the police apprehend the singer Frida (Nadia Saïji) in Paris’s 18th arrondissement, whose Goutte d’Or neighborhood is home to large numbers of French Maghrébi citizens and Maghrébi immigrants, including ones who are “sans papiers” (“illegal,” literally “without papers”). While chatting openly in Derja (Tunisian Arabic), Kalt uses her mobile phone to tag Frida’s digital identity in the police databank. Kalt gifts the benefits of royal Moroccan diplomatic privilege to her Tunisian friend. Since all Arabic dialects and languages are equally incomprehensible to the French police officer, Frida is even released with an apology typically reserved only for VIPs. Frida is nonetheless irritated by the banality of racial profiling as a form of state security and jokes about writing an “IHATEYOU virus” like the actual “ILOVEYOU virus” that infected an estimated five million computers a few years earlier in May 2000 and allegedly prompted the Pentagon and CIA in the United States and the Parliament in the United Kingdom to close their email servers. Instead of a virus, Kalt invents “bedwin”—part culture jamming, part political protest—represented by the playful figure of the camel.

Although Julia (Muriel Solvay) at the Direction de la Surveillance du Territoire (DST, or Directorate of Territorial Surveillance) does not immediately recognize her former lover and classmate Kalt behind the mobile tampering with police records or the camel that interrupts television broadcasts of football matches, archival newsreels, Hollywood movies, and U.S. “football games”; Kalt recognizes Julia as the DST agent who attempts to track her every move (images 5-6). Bedwin Hacker, then, focuses not only on ways that surveillance makes the brown bodies of Tunisian women legible to the state as suspicious, but also on ways that disinformation makes the white bodies of French women legible to the state as patriotic. Operating under the codename “Agent Marianne,” Julia is linked to the figure of La Marianne, the emblem for the French Republic that combines the allegorical figures of Liberty and Reason. Within the context of the film, Julia’s codename suggests the incommensurable differences within French citizenship and territoriality that are experienced as race/ethnicity, gender, sexuality, class, and religion. For El Fani, Kalt represents a “free spirit” from “south of the Mediterranean” that rarely appears in the French media: Kalt is “la liberté” (freedom), which Julia constrains and her French Maghrébi boyfriend Chems (Tomer Sisley) misrecognizes himself as possessing.4

Bedwin is impossible to decipher definitively. The camel is both whimsical, drawing comparisons with the Old Joe mascot for Camel cigarettes which allegedly evoked the “romantic spirit of the Middle East” (image 14), and purposeful, finding “enemies” to the left and to the right (images 2 & 4).5 Bedwin is imagined as threatening by people who are predisposed find anyone from or anything evoking MENA to be inherently threatening, as aspect of French civilization that has been parodied in other films by French Maghrébi filmmakers, such as Abdelkrim Bahloul’s Un Vampire Au Paradis (France 1992) in which the spontaneous and unconscious phrases uttered in Arabic by a young French woman are attributed to a possible encounter with an “arabe.”6 Bedwin evokes the interruptions of culture jamming, functioning at the level of information in the face of state disinformation: “in the third millennium, there exist other epochs, other places, other lives: we are not mirages,” signed in Arabic as “Bedwin” (بدوين not بدوي or bedawi) and in French as “Bedwin Hacker” (image 13).

The signal does not reach “Africa or Asia,” pointing out that French people in France might most urgently need bedwin’s contestation of French disinformation. Other epochs, places, and lives have presumably advanced beyond eurocentrism, suggested by a scene in which a French Maghrébi family shares the amusement of bedwin’s unexpected appearance on television (image 11). At the DST, everyone is afraid of the camel. Julia is scarcely comforted by her own belief that the camel’s messages do not indicate Islamic extremists since the accompanying Arabic-language text does not include the phrase “Allahu Akbar” (“God is great”). For Julia and her colleagues, Islam is a threat to state secularism that Christianity and Judaism are not. The DST reacts, rather than responds, to bedwin with its standard operating procedure of disinformation (image 5). By contrast, Kalt’s father understands his daughter’s work as repairing computers from a remote location. His understanding is an interpretation of hacking and jamming as an important work for adapting technologies towards democratic ends and countering the disinformation from both the Tunisian and French states.

Bedwin counters state disinformation and media misinformation with new information: “I am not a technical error”. In relation to the film’s focus on pro-xenophobia/anti-immigration discourses, it reminds everyone that French Maghrébis, whether citizens of France or Tunisia, both or elsewhere, are a transnational population that is not a “technical error” of colonial civilizing missions but rather the evolution of transnational encounters and exchanges that manifests itself in multi-directional assimilations, notably “génération beur” in the 1990s. The camel wears jeans (denim trousers) and babouches (leather slippers), protesting against those who “hate the sound of babouches” and aligning which those who will “go out in the streets” wearing their own babouches since “bedwin is always/still alive.” In another scene, the camel again affirms that “bedwin is not a technical error,” while wearing a jalabiyya (a garment with a wider cut than a dishdasha, kandura, or thawb) (image 2). Bedwin is equally at ease in any type of clothing. In this image, the camel’s pose also recalls the allegorical figure of La Liberté, particularly in Eugène Delacroix’s La liberté guidant le people (1833), reproduced on the 100FF banknote when French currency still existed (images 7 & 9). Another appearance of the camel in this pose is accompanied by the text “zap reality,” suggesting that the villain for everyone—citizens and noncitizens, alike—is really the media misinformation and state disinformation that has been promoted as “reality” constructed according to the political realism of the state and propagated in the idioms of journalistic, televisual, and cinematic realism.

The “reality” that requires “zapping” is the one constructed from surveillance and disinformation that extends the past of the French Empire into the present of the Francophonie. Camel-crossing road signs and satellite transmitters in the same desert suggest forms of power that function according to a logic that might not resister according to French systems of knowledge. In Kalt’s lab, camel figurines appear in proximity to computers whose screens reveal code and in proximity to windows that reveal desert landscapes, mirroring both foreign cigarette packets (image 8) and familiar road signs (image 12). The film’s use of visual parallels— Kalt’s and Julia’s short hair styles (images 5-6), the dunes of the Sahara and the landscape of hard drives— point to ways that borders are arbitrary, whether between genders and sexualities or between state control of movements of people and information. Jamming serves as a potential means of hacking. If Bedwin Hacker is shutdown, then Kalt and her young female assistant will launch Zoulou Hackers as “hackers for peace”, which counters another vector of colonial disinformation that Zulus were warriors against “progress” defined in colonial terms and resituates Zulus as warriors within ongoing anti-colonial struggles in a digital realm. Bedwin questions self-understanding, not only for “confused” characters like Chems, but also for everyone, suggesting that there might be “universal” liberating effects of “becoming bedwin”.

Often contextualized as an anomaly—a first Arab sci-fi flick, a first African cyber-thriller—Bedwin Hacker reflects what most of the world already knows: innovation and knowledge tends to “bubble up” rather than “trickle down.” Moreover, this bubbling up from what was once called the East, Third World, or Global South often consists in actual practice of the great innovations, such as modernity, secularity, and democracy, by what was once called the West, First World, or Global North. Although Tunisia has historically figured as an exception—modern, secular, European-oriented—in the French imaginary, it nonetheless remained proximate to, if not constituent of, the backwardness that France attributes to its former colonies and protectorates in order to reaffirm its own sense of exceptionalism—and global relevance in an era of new economically powerful republics, such as India, Brazil, and South Africa. Foreign perceptions of Tunisia’s exceptionalism in the MENA region vis-à-vis women’s rights allowed Ben Ali’s administration to censor newspapers and regulate use of the Internet on par with other regional “enemies of the Internet”—Libya, Saudi Arabia, and Syria—according to Reporters Sans Frontières.7

As Joseph Gugler points out, like many transnational films, Bedwin Hacker addresses itself to several different audiences with different relationships to Tunisia and France, to racial profiling and digital literacy. For audiences unfamiliar with MENA, Bedwin Hacker provides insights into what have been called the “south-to-north” migrations of technological and epistemological innovations, such as Ushahidi crowd-sourcing software. In El Fani’s film, innovations also take forms that might be called “east-to-west” or “female-to-male” migrations. Bedwin Hacker confronts the lingering orientalisms in eurocentric media like CNN and The New York Times that were surprised over imagined incongruence (“Arabs, Muslims… nomads, they’re on Facebook and Twitter?”) and then enthusiastic over belated recognition (“We’re all on Facebook and Twitter!”), for example, when Tunisians and Egyptians mobilized social media for social change in early 2011, perhaps even more so than when Iranians did the same in 2008.

“Rather than arguing for greater access and more balanced representation on behalf of the global South,” argues Suzanne Gauch, “Bedwin Hacker exposes the less visible restrictions placed on expression and communication in the global North.”8 In this way, the film disrupts assumptions that freedom and democracy flow exclusively from north to south, west to east, or male to female. Kalt’s bedwin suggests that practices and forms of feminism can flow from Tunisia to France, perhaps even liberating Agent Marianne from the bonds of servitude to the male-only fraternity of the French Republic’s “liberté, égalité, fraternité”; that is, from being an abstract symbol—as in Delacroix’s topless revolutionary—to becoming a material (or virtual) agent. Adhering to principles of hijab (modesty), for example, Asmaa Mahfouz’s video is credited with rallying Egyptians to Tahrir Square on 25 January 2011 to protest state policies of all kinds, including ones of disinformation that were used to discredit previous anti-government protests on the square. Nothing could be more destablizing to the sense of superior French/European/Northern/Western civilization embodied by Julia’s colonial-war–veteran boss, who fought for France in the Algerian Revolution (1954–1962), than to learn something about civilization, modernity, and secularity from a woman in Algeria’s neighbor Tunisia.

Image Credits:

1–6. Bedwin Hacker (2002). Nadia El Fani. Cinema Libre Distribution, 2006. Screen shots by author.

7. Cent francs banknote with Delacroix and La Liberté (1978). French Bank Notes, Dave Mills.

8. Camel cigarette packaging (1915).

9. Eugène Delacroix’s La liberté guidant le people (1833). Wikimedia Commons.

10-13. Bedwin Hacker (2002). Nadia El Fani. Cinema Libre Distribution, 2006. Screen shots by author.

14. Old Joe in advertisement for Camel cigarettes (c. 1990s).

- Verlan is a slang practice of inverting syllables in French words that takes its name from the inverted syllables of the word l’invers (the inverse). Slang comparable to cyber slang appears in film titles of banlieue (“outskirts,” literally “suburbs”) films by white filmmakers, such as Ma 6-T va crack-er/My City is Going to Crack (France 1997; dir. Jean-François Richet) in which the word cité (“hood,” literally “city”) is written as “6-T.” [↩]

- The verlan terms “beur” and “rebu” invert the stigma of the French term “arabe” as it is used despairingly to contain ethnic, cultural, religious, linguistic, and generational diversity into a single visible minority. A monolithic French identity hinges on the idea of Les Français de souche, the so-called indigenous French, who allegedly trace their roots to the Gaulois rather than to the Revolution. Political parties on the Far Right, such as the Front national (National Front), embrace the idea of les Français de souche in pro-xenophobia/anti-immigrant campaigns and other racist endeavors. [↩]

- In the United States, where the investigative journalism is increasingly “outsourced” to Google searches, AJE’s television broadcasts would make a much needed critical intervention and supply a much needed demand, yet AJE is effectively silenced by cable and satellite providers that do not include it in their packages. [↩]

- In “Casser les clichés : à propos de Bedwin Hacker,” interview with Nadia El Fani by Olivier Barlet, Africultures (May 2002), http://www.africultures.com/php/index.php?nav=article&no=2511, El Fani explains: “J’avais envie de dire qu’au Sud de la Méditerranée on trouve des esprits libres. Nos images ne sont pas diffusées au Nord et il en ressort un malentendu terrible qui fait croire aux gens qu’on est des arriérés et qu’on ne vit pas en 2002. […] Oui, Kalt représente la liberté : elle avait le choix de « devenir quelqu’un » dans cette société française mais a préféré une société où elle n’est pas libre, ce qui est en fait le sommum de la liberté. Julia est celle qui essaye de contenir la liberté des autres et Chems est celui qui, comme la plupart des gens, croit qu’il est libre mais se trompe tout le temps.” [↩]

- This expression appears in “Camel Cigarettes,” Cig Area: Cheap Tobacco Store (2012): http://www.cigarea.com/articles/camel_cigarettes.html [↩]

- Dale Hudson, “Transpolitical Spaces within Transnational French Cinemas: Vampires and the Illusions of National Borders and Universal Citizenship,” French Cultural Studies 22.2 (May 2011): 111–126. [↩]

- Suzanne Gauch, “Jamming Civilizational Discourse: Nadia El Fani’s Bedwin Hacker,” Screen 52.1 (spring 2011): 31; Albrecht Hofheinz, “Arab Internet Use: Popular Trends and Public Impact,” in Arab Media and Political Renewal: Community Legitimacy and Public Life, ed. Naomi Sakr (London, UK and New York, USA: I.B. Tauris, 2009): 57. El Fani’s recent documentary on post–Ben-Ali Tunisia Laïcité, Inch’Allah! (Tunisia-France 2011), oddly translated into English as Neither Allah, Nor Master, examines discussions that now take place. [↩]

- Suzanne Gauch, “Jamming Civilizational Discourse: Nadia El Fani’s Bedwin Hacker,” Screen 52.1 (spring 2011): 30–31. [↩]

delighted you share my enthusiasm for Bedwin Hacker. can you give me a transliteration (including ayn and hamza) of the arabic title of the film?