Underwater Flow

Nicole Starosielski / Miami University

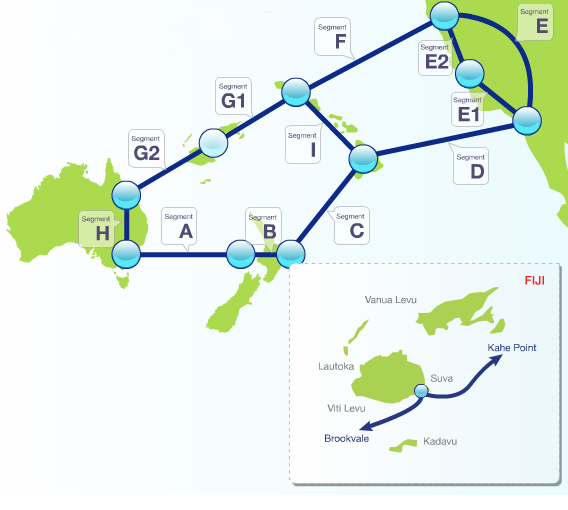

If you are viewing this article outside of the continental United States, it has likely been transmitted to you via undersea cable. While satellites are still used for a significant portion of television distribution, almost all of the texts, images, and videos on the internet are transformed into light and transported by fiber-optic cables. To travel to New Zealand, this article would probably leave the United States at Morro Bay, California (a hub for cable traffic located between Los Angeles and San Francisco), move along the very bottom of the seafloor to Hawai‘i, and then south to a beach on Auckland’s north shore. Alternatively, it might go the long way: departing the United States at Nedonna Beach in Oregon, stopping next to the tent cities on O‘ahu’s west shore, surfacing near a rifle range in Fiji, routing through Sydney, Australia, and then looping back across the Tasman Sea to New Zealand. Given the speed of cable systems, the difference between these paths would not be noticeable to ordinary users. If you comment on this page from a computer in New Zealand, your words will most likely travel along one of these routes underneath the ocean. Though we tend to think of the internet as less and less wired, in many cases it is only in the last hop between mobile devices, routers, and cell phone towers that the signal becomes wireless.

Questions about internet distribution are often framed in terms of users’ access and examined primarily at the point of consumption. This approach provides only a partial understanding of digital media flows, as it fails to register how the infrastructures that support these signals matter and the ways that cable routing makes a difference. Cable routes are places where media systems can be disrupted or delayed, as infrastructures become imbricated within local politics. There is a major problem with landing new cables in California, for example, because of historical conflicts with environmentalists and fishermen. Cable paths are also zones where local media uses can come to shape infrastructure development (and are influenced by them).

The routing of undersea cables has a critical impact on media geographies in part because they are relatively scarce infrastructures. All western-bound internet traffic on cables is funneled from the Americas to Asia through less than ten points on the United States’ Pacific coast (some of which have been in operation since the 1960s). The above routes on the Southern Cross Cable Network comprise the only cable links between New Zealand and the rest of the world (though negotiations are forthcoming for a possible second system). They are landed at the same points as the two British telegraph lines that were established almost a hundred years ago. The small number of cables does not necessarily limit the information flow out of the country, however, since each can support an enormous amount of capacity. One new cable between Australia and Guam, for example, has enough capacity for everyone in Australia to make a phone call at the same time (over 20 million people). These systems are few and far between in part due to their extraordinary expense: they can cost over a billion dollars to establish and maintain.

Tracking signals as they extend through the air, under ground, and under water can help us to grasp the fundamental materiality of our media systems. Locating the technologies that carry them and documenting their pathways contributes to a politics of infrastructural visibility – the effort to reveal the hidden systems underlying our network society. It can also help to explain how patterns in media creation, circulation, and use are intertwined with developments in infrastructure. This column takes up the latter issue, charting three of the ways that undersea cables inflect (and are impacted by) the more visible practices of media production and consumption.

Signals depart from a cable landing point in New Zealand

1. Fiber-optic cables are a necessary (but not sufficient) condition for bandwidth-intensive global industries, and as such, they shape possibilities for transnational media collaboration. At the most basic level, immediate and reliable access to the internet is critical for cities that want to gain a foothold in the market for on-location Hollywood productions, or which aspire to become media capitals. Cables are especially important for work that depends on digitization, including digital animation and special effects, since high-speed links render the frequent and instantaneous sharing of high-resolution video effective and economical. For example, the collaborations on Avatar1 between Weta Digital in New Zealand and Industrial Light & Magic in California would not have be possible without the Southern Cross Cable Network. As a result, Weta Digital has a major stake in the smooth operation of Southern Cross and generates a sizeable stream of traffic that helps to sustain their network. Media industries can be jeopardized if cable networks are not reliable. Likewise, some cable networks depend on media industries and transnational collaboration as a significant source of revenue.

2. Because of their scarcity and their historical sedimentation in particular locations, undersea cables can exhibit a gravity that pulls in other kinds of (media) flows. Cables are at times seen by governments as a resource to be leveraged in the creation of new media industries and practices. The Fijian Government, having contributed a large amount of money for the Southern Cross Network, subsequently looked for a way to generate traffic and pay off their investment. They created Information and Communication Technology parks, call centers, and a new initiative, “Bulawood: The Hollywood of the South Pacific,” all of which depend on the cable for transnational exchange and which prominently feature the cable’s capacity in their marketing. Cable infrastructures, however, can also have unintended effects on the mediasphere. The relative accessibility of the internet via this same cable has invigorated Fiji’s illegal DVD distribution networks, which in turn compromises the government’s efforts to develop a media industry. Though zones at the periphery of international cable networks often gain a disproportionate potential for media-related development, this potential is rarely realized in the intended ways.

3. Changes in media content and consumption also influence the expansion and geographies of undersea cables. The move to high bandwidth visual media (driven by a growth in online video and gaming) forms a rationale for the construction of new networks. Cloud media applications, such as movie streaming via Netflix, Facebook games, and Google Docs, can generate new forms of traffic that make further cable development viable. However, the content shift from local cable distribution to internet distribution, and from local computer email to email based in the “cloud,” has significant impacts on the dispersion of media consumption. This tends not to be as much of a factor in the United States, since cloud-based content is often relatively accessible, stored domestically (in places like Oregon) and linked to the user via diverse underground cable routes. In many locations (such as Fiji), the shift means an increasing reliance on undersea cables (and other international communications infrastructure) to connect to content that may have previously been locally available. And yet, given the scarcity and expense of undersea cables, not every location will get one and many will be lucky to have two. Pricing often remains high, especially along thin routes, and these systems are expensive to maintain. Transitions in the mediasphere that require more international traffic (such as cloud computing), could contribute to inequality and dependence at the level of media access even as they stimulate the expansion of infrastructure.

As our culture pushes onwards towards higher-definition visual content, the distribution of film, television, and other media via undersea cables is set to increase. By following the routes of these transmissions we might better understand how cables are intertwined with the industries that use them, the content that is transmitted over them, and the everyday practices media users engage in. Moreover, tracking media flows as they extend underwater draws our attention to the ways that seemingly nebulous digital circulations are always anchored in material coordinates. While infrastructure sites do not determine the direction of the flows they carry, they nonetheless contort and deform the media landscape.

Image Credits:

1. Taken by the author

2. Southern Cross Cable Network

3. Taken by the author

4. Taken by the author

5. Taken by the author

Please feel free to comment.

- Cameron, 2009 [↩]

Nicole,

Extraordinary work. This is the type of research/criticism that should be more prevalent in scholarly circles. By discussing the means of production/distribution, you make compelling insights about what other issues might “flow” from there. Observing material/historical conditions and THEN looking at the effects is quite rare within academic prose these days. Well done, and hopefully, this kind of critique will inspire imitators who will develop more insights based upon what you’ve done here. Excellent.

Interesting article! I’ve enjoyed reading it. I was mostly interested in how the content moves overseas and I admit, I didn’t think so much about the distribution technologies that impact the flows of content. In your article, you point out that the push towards high-def content will further the gap of technologies between the countries. I thought that added more depth to the media content flow; normally when looking at the flows it’s just about does the audience get access to program or not. But after reading your article, I thought maybe when analyzing the flows of media content, we should see if the content if offered in high-definition, 3D, or other high technologies or just ‘standardized’ versions.