Player Hater

Jonathan Sterne / McGill University

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tHcc6mv2KLc[/youtube]

Does the World Wide Web have a soundtrack?

On its face, the question is silly: of course it doesn’t, at least not in the same way that cinema and television are said to have soundtracks (pace Michel Chion, 1994). But anyone inquiring into the aesthetics and phenomenology of the web ought to spend some time ruminating on the status of sound online.

In its many manifestations, the web is a sometimes-synchronous medium (which also undermines the still-too-frequent and gratuitous claim that the web somehow descended from cinema or television).2 Whereas in television, the soundtrack comes to you and must be muted if you want quiet, online the relationship is inverted.3 By default, the web is quiet—or expected to be quiet anyway—and sound is supposed to be something to which the browser actively transitions.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wM1BJVN8zD0[/youtube]

One interesting effect of this arrangement is that the ambiance function usually attributed to film and TV soundtracks operates instead the visual register through the use of backgrounds, animations in sidebars, and header images, more along the lines of newspapers and magazines. Or if we want to stretch the cinema-and-TV metaphor close to breaking, we could say that the mise-en-scene of webpages has to do twice the work. But more importantly, given that the web is fundamentally audiovisual (if sometimes clumsily so), a set of techniques and conventions have emerged to allow users to transition from a silent to a sounded web, most often through pressing “play” on an audio player, with its ubiquitous right-facing triangle “play” button (which often turns into the parallel lines “pause” button).

The play button’s history has yet to be fully traced, but the existing conventional wisdom has it emerging with the audio tape deck. While most consumer cassettes spooled from left to right, this is not universally the case in tape machines more generally, and certainly other devices, from video cassette recorders to projectors, spool their filament in a variety of configurations. Today, these symbols are among the “best understood” in the world (Brigham 2001, 118), due in part to a thoroughly globalized consumer electronics industry.4

As Bill DeRouchey has pointed out, these “buttons” aren’t buttons at all, but rather actionable items on a screen, which used to require the mouse button as an adjunct, but with touchscreens no longer even require that. The play or pause “button” is therefore a sign which refers to a sign, which itself may or may not have referred to the likeness of a process (depending on which direction the tape was going). My Peirce is a little rusty, but the play button looks like an “argument” to me, the most abstract of signs.

And yet it does suggest some things about directionality. The left-to-right movement is not an accident, given the supremacy of English on the Internet and the general left-to-right movement implied by reading in English online. But as a metaphor, the left to right progress of time become considerably more weighted when we consider the companion of play, the progress bar.

In the progress bar, songs, TV clips, movie shorts and animal videos share the temporal arc of the novel. True, if you let your buffer do its work, you can scrub your content, but then, you could also skip around The Great Gatsby or Gravity’s Rainbow simply by flipping through pages. Random access is not natively digital. It is not that the linear time is imposed from without (after all, every band I’ve been in has played songs from beginning to end and not some other way). The problem is that the progress bar represents but one dimension of the temporality of the content.

As John Durham Peters has argued, one of the fundamental insights of media studies is that “texts cannot be interpreted apart from the processes that produced them.” And in online players, we find processes that attempt to interpret themselves for us.

This is particularly the case for the SoundCloud player. In addition to the play/pause nexus and the progress bar, the SoundCloud player adds another dimension: the amplitude waveform, which is meant as an indicator of relative loudness. The quieter parts of the recording hew closer to the center, the louder parts reach out toward the edges. It also does other things. It can offer a sense of parts of the song, such as the difference between verse and chorus, or when it really kicks in after a quieter intro. Combined with the timeline, SoundCloud has cleverly provided a way for artists and listeners to add time-stamped commentary on the recording.

Here a recording where the amplitude information in the SoundCloud waveform might be somewhat useful:

And here’s one where the visual logic of the player gives little clue as to changes in what is heard:5

Woodcarver by A Tribe Called Red

(Beatport has also adoped the waveform, but I couldn’t figure out a way to embed their waveform representation in this article, since it’s not posted on Facebook.)

But all of this suggests a transparency that’s not really there. All three examples sound totally different, and yet the waveform gives no indication of timbre. Further, the measure of relative volume is pretty crude. No serious psychoacoustician or psychologist of music would argue that perception of loudness neatly correlates to these kinds of machine measurements. In fact, whole fields of technology have been developed on the basis of the difference between what machines measure and what people actually hear (for more discussion of the cultural politics of psychoacoustics, see Sterne 2012). But the waveform is a standard signifier for “sound” inside a computer or sound editing program. It is most often taken as an indexical representation of what comes out of the speakers.

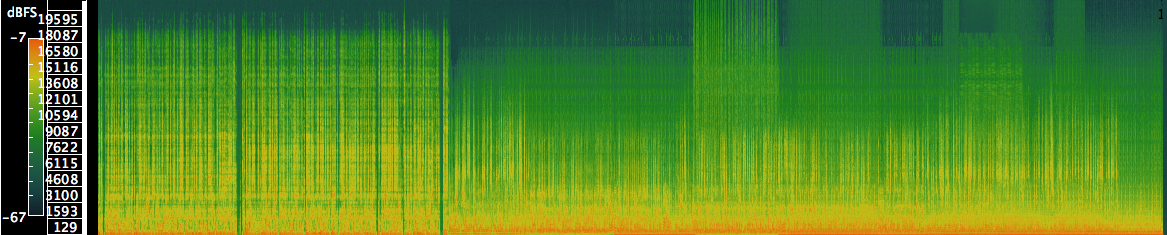

This is choice is not automatic. The history of visual interfaces for sound on computers also needs to be written, but in lieu of history, let us go with a little speculation: the waveform appears to have descended from oscilloscope, which showed the shape and intensity of signals passed through it. This is an interesting choice, since theoretically sound software could work with sound spectrograms, which present frequency and intensity, and therefore a different kind of (and potentially more useful) visual information at a glance. If that’s not enough, they are also more colorful, and more important for the history of twentieth century communication technologies (Mills 2010).

Below is a spectrogram of the footnotes, although it’s very small so it can fit into this column. Even without any training, you can still see that the frequency content of the recording (and therefore what’s on it) changes over time.

In addition to the spectrogram, there are many other possibilities for representing sound online. For instance, could imaging all sorts of spinning, turning icons, which might get at some of the other temporalities so central to sonic experience (like rhythm). But for now let us close with an actually existing example: Erik Loyer’s waveform “bodies” designed for Sharon Daniel’s Blood Sugar (attn. Jobs hagiographers: Flash still required). In this piece, we see what looks like standard waveform representations of audio recordings, but as Loyer explains, “the amplitude of these visual waveforms are determined not by the volume of the audio for each interview, but instead by the density of Sharon’s annotations at any given time.” In other words, they reflect a conscious decision regarding what is visually important to emphasize in the audio. While we might not aspire for every EDM nerd’s latest SoundCloud mix to undergo an elaborate process of theorization before it gets uploaded, large swaths of the web rely on a few extremely limited techniques for the visual representation of audio online. Understanding those techniques, studying their history, and developing a critical vocabulary will be important first steps in taking greater advantage of the medium’s vast and plastic potential.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iamp67bPiek[/youtube]

Image Credits:

Images provided by the author.

Notes:

Altman, Rick. 1986. Television/Sound. In Studies in Entertainment, 39-54. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Brigham, Fred. 2001. “Graphical symbols for consumer products in an international context.” Information Design Journal 10 (2): 115-123.

Chion, Michel. 1994. Audio-Vision. New York: Columbia University Press.

Downey, Gregory John. 2008. Closed Captioning: Subtitling, Stenography, and the Digital Convergence of Text with Television. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Eisenstein, Sergei. 1969. Film Form. New York: Harvest Books.

Eisler, Hanns. 1947. Composing for the films. New York: Oxford Univ. Press.

McCarthy, Anna. 2001. Ambient Television: Visual Culture and Public Space. Durham N.C.: Duke University Press.

Mills, Mara. 2010. “Deaf Jam: From Inscription to Reproduction to Information.” Social Text 28 (1): 35-58.

Mowitt, John. 1992. Text: the Genealogy of an Antidisciplinary Object. Durham: Duke University Press.

Rodowick, David. 2007. The Virtual Life of Film. Cambrdige: Harvard University Press.

Sconce, Jeffrey. 2004. What If? Charting Television’s New Textual Boundaries. In Television After TV: Essays on a Medium in Transition, ed. Lynn Spigel and Jan Olsson, 93-112. Durham: Duke University Press.

Sterne, Jonathan. 2012. MP3: The Meaning of a Format. Durham: Duke University Press.

Please feel free to comment.

Pingback: Also just out, yet another essay entitled “player hater”

Thank you for the great article! You do a good job making your point through the audio links and demonstrations of sound media players. Soundcloud is an interesting site because it mimics showing a group friends/acquaintances your new song you recorded/created, but depending on where/how the website-user is listening to the MP3 and its limited audio information, each listener will potentially be hearing different-sounding mixes.