The Compassion Manifesto: Corporate Media and the Ethic of Care

Randy Lewis/ The University of Texas at Austin

During a recent Republican Presidential debate, Texas Congressman Ron Paul was asked how he would apply his libertarian philosophy to the case of a gravely ill American who could not afford health care. Even before the candidate could answer the dramatic question, parts of the audience erupted into a small Roman orgy of ghoulish cheering that seemed to say, “Hell yeah! Let ‘em die.”1

TV pundits immediately seized on this apparent display of heartlessness. Much to his credit, MSNBC’s Chris Matthews was incredulous about these lusty expressions of cruelty, which he saw as part of larger “hatred of people who are in trouble, who are vulnerable” in America today.2 However, Matthews and his talk-show colleagues seemed oblivious to the ways in which they are part of the problem: simply put, commercial television has increasingly skewed toward a meaner view of life in recent years.

Think about it: when was the last time you saw an act of charity on TV? In the strictly for-profit world of corporate media that dominates our nightly viewing, caring for strangers has lost out to macho indifference, consumerist narcissism, and paranoid stranger-danger. Except in rare circumstances, we are not permitted to witness ongoing suffering nor those who tend to it. This omission is one of the defining facts of our contemporary mediascape.

Let me be clear: I’m not talking about those periodic moments of telegenic ruin when Anderson Cooper choppers in for a few weeks of sober glances at the problem. I’m talking about the day-to-day shit through which people slog and activists struggle: unsafe water, inadequate food, abusive institutions, cruel economics, uncertain prospects, epic despair. Where do we bear witness to that pain in the age of the screen? When do we imagine ourselves in solidarity with those who suffer?

Maybe John Winthrop saw it coming in 1630 when he warned the new colonists in Massachusetts to remain “knitt together” like the “ligaments” of a body, and that “perticuler estates cannot subsist in the ruine of the publique.” For reasons both theological and practical, Winthrop put charity and interdependence at the center of his political vision, not the unfettered individualism and “dog-eat-dog” bravado that become dominant. The Puritan governor even sketched out the proper response to a “community of peril.” (Hint: he didn’t suggest that letting them die would be “Christian,” but instead argued for compassion and aid).

Not that his advice did much good. You can ask the Pequots who faced Puritan muskets in 1637, or Anne Hutchinson who was banished for heresy the following year. From the earliest moments of settlement, European Americans were unable to remain “knitt together” in a compassionate polity for very long.

The modern history of our republic bears out this view of a disconnected, distrustful populace. In recent decades, “social capital,” that sociological measure of goodwill between citizens, has performed as miserably as the financial capital now withering in our 401k accounts. Writing about the “waning of faith in our fellow citizens” in 2008, political scientist Eric M. Uslaner noted, “Trust in other people has fallen dramatically in the United States over the past four decades as Americans have become less engaged in their communities.”3 As has been widely noted and often debated, the age of television has also been the age of distrust, marked by a decreasing commitment to volunteerism, local charities, and other traditional forms of civic engagement.

I’m not suggesting that corporate media bear sole responsibility for this apparent culture of disconnection and uncaring. For this, we can thank a nerve-wracking economic landscape as well as deeper national mythologies such as a rampant individualism that makes us skeptical of anything except self-reliance; a “winner takes all” American dream in which first place is a Cadillac, second place a set of steak knives; and an endemic culture of militarization that enshrines vengeance at the expense of understanding. These stern ideas often conspire against our charitable instincts, something we might notice if we weren’t flooded with self-congratulatory rhetoric about own “exceptional” status. We are told, simply because we are Americans, that we are more giving, caring, and righteous than any other nation and that we need not sacrifice the smallest personal whim to benefit the commonwealth. In the brave new world of neoliberal cynicism, charity really does begin at home.

Perversely, media corporations ask us to empathize with strangers who don’t need our help. As we watch highly rated reality programs like Celebrity Apprentice or The Real Housewives of Orange County, we are invited to feel a kind of aspirational solidarity with Donald Trump and other millionaires whose ranks we supposedly expect to join (and thus must not tax). It’s not just Megan Wants a Millionaire. Everyone in TV-land is encouraged to share this “natural” desire to put glamorous self-interest above boring, old communitas.4 And not surprisingly, we seem to have a much harder time envisioning ourselves in solidarity with less fortunate people, especially when racial or cultural difference is a factor.5

Let’s be frank. While we are constantly told that we are a caring people, that even the stingiest miser can call himself a “compassionate conservative” with a straight face, we spend countless hours in a mediascape that circulates cruelty, competition, consumerism, and snark. How often are we asked to care about civilian casualties in our endless wars, or poor neighborhoods in New Orleans where people are still reeling from Katrina’s wake? Hollywood cinema, reality TV, and even cable news flit past these continuing stories, barely allowing them to register.6 Does the nightly news focus on the one-in-four rate of child poverty in Texas as it much as it marvels at Rick Perry’s cowboy swagger?7 Even if sociological reality intrudes on our narcotic dreamscape (and scholars of print media have shown that this happens mostly around Christmas), we can simply tune it out.8 Dancing with the Stars is calling our name.

How stark is the contrast with a book I read over the summer: Rebecca Anne Allahyari’s Visions of Charity: Volunteer Workers and Moral Community. A gifted qualitative sociologist, Allahyari “illuminates the construction of caring selves in the work of feeding the urban poor,” suggesting how “moral selves” develop in the process of caring for those in need. Using The Salvation Army and Loaves and Fishes as her case studies, she examines how people volunteering in soup kitchens find themselves improved, even transformed, through the process of helping others.

What is striking about this book is not the careful insights of good scholarship, especially when rooted in a scholar’s own ethic of care. Instead, it is how much it exists in contradistinction to the ethic of uncaring in commercial media. After reading Allahyari’s work, I worried not simply for invisible victims of hunger, poverty, or homelessness; I became increasingly concerned about the rest of us who tolerate (or tune out) these often unseen ravages. I began to wonder if corporate media discourages us from seeing the structural pain in our midst, if its consumerist agenda is dominating what could be an important forum for “moral selving.” When it comes to unsensational forms of suffering, the enduring structural binds into which millions of Americans are born, corporate media seems unable to visualize it (or its relief) in any but the most superficial and fleeting forms.

Of course, compassion does receive some lip service on cable television. For instance, we have the “two minute care,” the sanctimonious inversion of the Orwellian “two minute hate.” Usually shoehorned into the end of an evening news program or a morning talk show, these brief “human interest” stories display some small act of decency before returning us to the cruel torrent of commercial media. This grotesque system has even spawned a celebrity commentator who cares so much that she shakes with a demented fury. Nancy Grace’s nightly outrage about victimized children is really a call to vengeance, not a moment for understanding (and preventing) the structural factors that are ultimately responsible for the horrific cases that she addresses. Perversely, Nancy Grace offers “caring” in the form of Old Testament punishment: she sells the moral superiority of the vengeful media mob, the cleansing furies of self-righteous blather.

Some observers might expect to find an “ethic of care” woven throughout our television dramas and movies, where we are occasionally invited to identify with characters in need. But for every thoughtful investigation of human misery like The Wire, we can find a dozen problematic depictions of suffering and its relief. Consider the unctuous do-goodism of Netflix’s most popular rental ever, The Blind Side (2009), a movie that shows how wealthy white Southern women can bring semi-mute, homeless, African American male teenagers to the promised land of white suburban mansions and Christian private schools. The lesson is clear: with sassy blond saviors (who are never to be touched), athletic prowess, and an extra helping of Jesus in their corner, impoverished African American men will make out just fine. In other words, privatized, individualized, and racialized compassion is the best we can imagine for ourselves.

Or consider the depiction of traumatized victims in Law and Order or CSI-Wherever. In these ubiquitous crime dramas, horrific suffering is presented only so that our high fashion detectives have something to brood over in their sun-drenched, pastel-themed crime labs. A child slavery ring or Saw-quality domestic abuse is little more than an occasion to whip out improbable crime-solving gizmos, fish around for semen and blood, and make self-righteous speeches about justice and “finding closure.” And let’s not forget the conceptual cornerstone of these crime dramas: the graphic vivisection of the victim. Perhaps I’m bending Winthrop’s metaphor too much, but it seems to resonate in the current craze for dismemberment. We can’t visualize being “knit together,” but with the help of CSI’s vivisection aesthetic, we can easily imagine being sawn apart.

It’s not all that bad. Occasionally, something humane slips past the slick machinery of corporate media. I am always genuinely moved to see Brad Pitt talking with Ellen DeGeneres about his home-building efforts in New Orleans. I am delighted that Sesame Street and a few other children’s programs celebrate kindness, giving, and compassion. And I am very grateful for the surprising exceptions to the uncharitable rule, such as the brilliant satire of Louis CK.

In one of the richest moments in recent television history, Louis CK began his eponymous show on FX with the comic standing in a crowded New York subway among a group of strangers. Teetering between existential ruin and an awkward embrace of his shared humanity, Louis studies his fellow passengers on the dirty train. Eventually his attention comes to rest on an African American woman recoiling from a vile mystery liquid on a nearby seat. Suddenly, Louis does something unexpected: he removes his shirt and begins to mop up the mess before it reaches the woman. Gazing at him with reverence, his train-mates marvel at his kindness and generosity. Why? Because Louis is breaking the code of mutual distrust and tending to needs of strangers, an uncanny echo of another bearded, bawdy talker from New York City. In the 1860s, Walt Whitman volunteered to help the wounded in Union military hospitals, caring for men with broken bodies and practicing his philosophy of loving “adherence.” Nowadays, Louis CK’s anguished humanism is the closest we come to Whitman’s unfashionable overflowing of unironic connectivity. But, of course, Louis CK has taken us into a hopeful fantasy, a dream sequence shot in melancholy black and white to mark its social implausibility. Wouldn’t it be nice, he seems to wonder before sliding back into an alienated stupor. Kindness is the new surrealism.

There is another partial exception: the big O. When it comes to charitable giving, I marvel at the deus ex machina that is Oprah Winfrey (as well as the overnight house fixer-uppers who run Extreme Makeover: Home Edition and similar shows). But I worry that Oprah is simply flipping The Blind Side on its head, racially speaking. Aside from a more progressive racial dynamic, Oprah still teaches us to assume the position of media serf, waiting for our celebrity overlords to dole out trinkets from magic TV land. It is the logic of the lottery.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fH4O5ymzzEs[/youtube]

I don’t want to sound like Scrooge McDuck. Of course, I’m glad Oprah handed out those Caribbean cruises, “Nikon D3100 Digital SLR Cameras,” and “Judith Ripka Eclipse Earrings.” But highly branded, spectacular giving is too idiosyncratic and ultimately too much about burnishing the nobility of the giver, whether it’s the corporation who donated the goods or the celebrity who’s doling them out. In Oprah: The Gospel of an Icon, a brilliant new book on Oprah and spirituality, Kathryn Lofton describes how the talk show host encourages her viewers to live charitably and compassionately, yet always “under the banner of self-love.” As Lofton points out, Oprah teaches us that charity and compassion are really a reflection of the giver’s greatness, and that her viewers’ “spiritual election correlates to their donating abilities.”9 While I would gladly take narcissistic charity over no charity at all, Oprah’s approach does seem to taint the “ethic of care” with a strong whiff of self-interest. The greater problem, of course, is the question of proportionality: big as it is, Oprah’s charity is rare in the overall mediascape. So, even if we accepted her work, prima facie, as a compassionate exception to the meanness of the media torrent, the cruel flow of normal programming still waits for us on almost every other channel.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gf5sU4SBKVs[/youtube]

For compassionate analysis, we must turn off corporate media and look elsewhere.10 Scholars, social workers, activists, novelists, serious journalists, documentary filmmakers, alternative media, and playwrights ask the deeper questions—you can learn more about suffering in three hours of Chekhov than in month of cable television.11

Yet I don’t blame television as a medium. I blame the gilded turd of corporate capitalism, our real American idol in a Biblical sense. Pitiless competition, not community, is the essence of corporate capitalism in the age without limits or accountability. Big media apologists sometimes claim that TV only holds a mirror to our desires, that it’s only giving the people what they want, no matter how dismal and cruel, Idiocracy-style. We are told that even if compassion and charity are social goods that we’d like to disseminate, they are not marketable goods that can compete with the Home Shopping Network or Spike TV’s 1000 Ways to Die.12

But the prime mover in all this isn’t ordinary people whose tastes are mysteriously becoming callous, but an utter disregard for social ethics on the part of big media producers. Simply put, corporate television reflects an underlying economic system that is increasingly divorced from humane, democratic principles, if not basic human decency.13 In the famous televised hearings in 1956, Sen. Joseph McCarthy was shamed with this question: “At long last, have you left no sense of decency?” Now the question could be turned on the corporate masters of an increasingly coldhearted medium.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fIqABIcKIvs[/youtube]

Of course, a corporation is never devoid of feelings. In fact, its marketing department is often quite skilled at manipulating anxiety, hope, desire, fear, and resentment in the ads that bludgeon our consciousness. But the multinational corporations that rule our world have no interest in our yearning to feel “knitt together” as a democractic culture, no real concern for our communal or even national well being, unless those feelings edge us toward particular brand identity or consumption constellation. My new VW makes me at one with the hipster twenty-somethings with interesting eyewear. My Hemi-powered Dodge Ram truck unites me with the steak-chomping Real Americans who hate Obamacare. Why be banded together in common cause to fight homelessness or hunger when we can be branded together as customers of a vast corporation?

With a knack for shameless sophistry, corporate apologists often hide behind the mantle of traditional values, even religious ones. But you are not “thy brother’s keeper” in the corporate mediascape: you are his rival for invidious distinction and lifestyle status points (or more likely, her rival, given increased poverty rates among women).14 Instead of exposing us to compassion, charity, and the possibility that we might be “knit together” as a nation in a form that doesn’t involve shopping or war, we are primed to indulge the constant, anxious re-fashioning of the self that encourages trips to the shopping mall and meetings with private security companies. To witness suffering, and valorize charity, would be a dangerous distraction from our identity as “citizen-consumer.”

But don’t we have a choice to turn the channel? Can’t we flip to something better, something more illuminating? Not really—and that is precisely the problem. As is so often the case with the “free market” illusion of choice, the rapid proliferation of channels has done little to alter the ideological consistency of the privatized mediascape. We simply get more of the same no matter where we look. I see plenty of it on my own TV. Because each month I am willing to mail off the equivalent of a used car payment, my friendly neighborhood media conglomerate grants me access to an infinite number of channels, almost none of which breaks the pattern I have been describing. Even the religious channels are often filled with a rhetoric of private salvation and harsh judgment, not collective responsibility or communal love (God forbid!).

What we need are real media alternatives, not the illusion of choice. We need the liberation network, the volunteer channel, the compassion hour. We need frequent invitations to feel and act in solidarity with people in need. In some ways, the conditions are ripe for an explosion of kindness, both in representation and actuality. Psychologist Steven Pinker’s latest book, The Better Angels of Our Nature, argues that cruelty and violence are at an all-time low in our evolutionary history. In some macro sense, we’re living in very kind times, even compared to our recent ancestors.15 Some observers have even worried that we’ve gone too far in the direction of compassion. In the last few months, one New York Times writer wondered if we’re “becoming compassionately numb,” while another asked if we were reaching the “limits of empathy.”16 A third asked if we had gone beyond “compassion fatigue” to some state of “pathological altruism” in which our giving knows no end.17

Maybe there is some validity to this “compassion boom” in the real world, but if so, why is it so absent from our media culture? No doubt, our real lives can require serious empathetic investments in child rearing, eldercare, and volunteerism, but these acts are rarely visible in our corporate media. If anything, I fear that corporate media will alienate us from our own more magnanimous instincts. It will blot out altruism with anxiety, compassion with competition.

There is an alternative where we can find a small but proven audience for compassionate media. Independent documentary has spoken to it for decades. While commercial media races to the bottom of dumpster of sensationalism, independent documentary has served as a powerful site of affective engagement, political mobilization, and aesthetic pleasure, often at the same time. For example, Marlon Riggs’ 1994 film, Tongues Untied, is a beautiful work of art that invites us to feel a connection to a community (gay African American men) that was traditionally disrespected or ignored in the mainstream media. Rigg’s film invites our empathy, compassion, and understanding, which lead to other forms of solidarity essential to a democratic culture. But you’ll never see it on cable television, not when the premium movie channels are running American Pie II, Indecent Proposal and Land of the Dead for the fifth time this week. Even PBS was fearful about running it when the film was first released.

I am worried about the affective states that American media culture generates, but also know that I am a part of the problem. I watch a great deal of violence and bile under the guise of entertainment (did I really need to watch Predators last night?). And I understand the reluctance to engage the stranger with compassion, even on screen. Growing up in grimy 1970s New Jersey, I was raised to fear the stranger, to watch from the window, and to flee solidarity. My poor Anglo-Irish grandparents were illegal immigrants who taught us to dread the informer’s eye, and to hide from “outsiders” of every stripe. You learned to horde, not help; you learned that charity was neither taken nor offered. No productive politics could take root in such a bitter soil, only a kind of Death Wish dread of the monsters disguised as “citizens” and “neighbors.”

That grinding skepticism of the social was a daunting inheritance, one that I’ve struggled to leave behind, often with the help of documentary film and other compassionate forms of creative expression. Certain films encouraged me to rethink what I knew as a teenager and to contemplate an ethic of care. For my younger self, documentary provided a safe place for Whitmanesque “adherence” (of a disembodied, postmodern variety), a contact zone that presented little risk but often led to more tangible forms of solidarity. The subterranean homeless in Dark Days, the mentally disabled in Best Boy, and the striking workers in American Dream were a crucial part of my sentimental education, encouraging me to pivot from bitter isolation to compassionate connection in my politics and teaching. Indeed, compassionate media was an important chapter in my moral history, and for this reason, I mourn its absence in the commercial mediascape where Americans spend so much of their non-laboring lives.18 What I came to realize in my callow twenties now seems obvious: a democratic culture cannot thrive in a climate of cold-heartedness and disconnection. As the philosopher Emmanuel Levinas argued, we need to embrace the stranger, to open ourselves to a non-reciprocal ethics that expects nothing in return—-to enter the dream-sequence with Louis CK on the subway, if you will, and then to make it real. After all, how we treat the least among us is the truest measure of our society’s worth. And by this standard, the corporate media is a foul tutor indeed.

Image Credits:

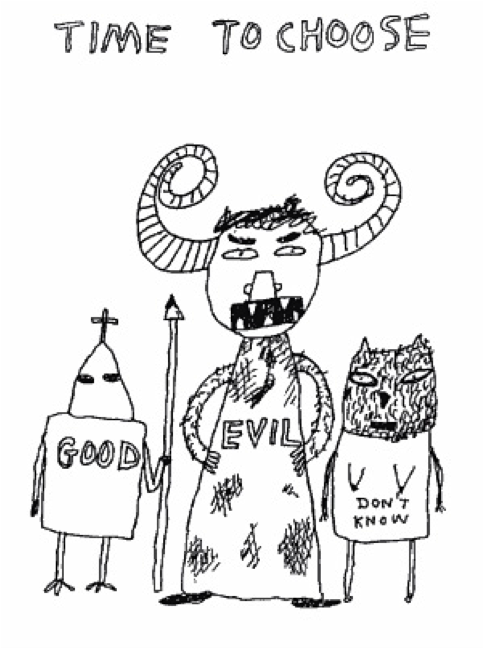

1. “Time to Choose” by David Shrigley

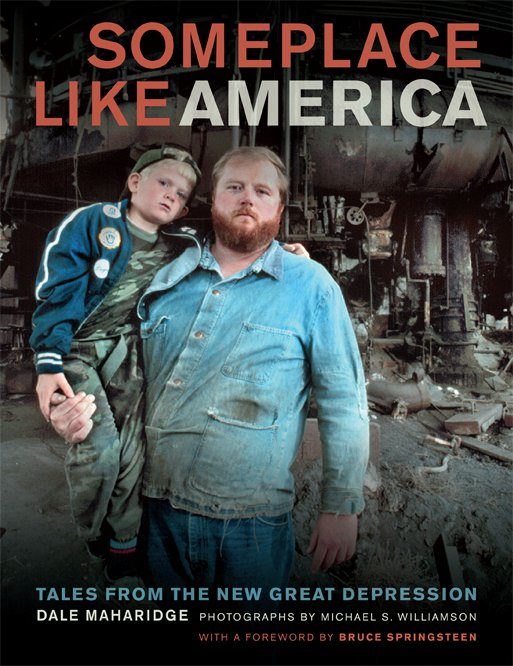

2. Someplace Like America podcast

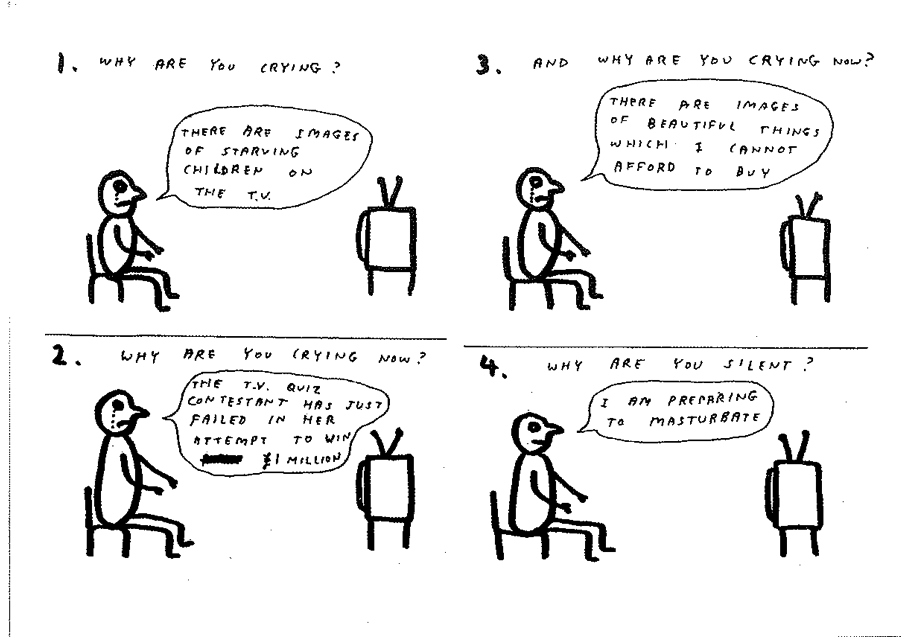

3. David Shrigley Cartoon

4. Extreme Makeover’s “branded giving” in action

5. Oprah’s Favorite Things

6. TED Talk by smug TV producer

Please feel free to comment.

- Ron Paul was not unique in expressing and eliciting uncharitable sentiments in the recent presidential debates. When Gov. Rick Perry touted his record number of executions, some members of the audience clapped as if he had scored a touchdown. Then, at another Republican debate a week later, the audience astonished many viewers at home by booing an active-duty gay soldier who appeared on video from Iraq. [↩]

- Chris Matthews, Hardball, MSNBC, September 23, 2011 [↩]

- Eric M. Uslaner, “Truth and Consequences,” in K. R. Gupta, Prasenjit Maiti, eds., Social Capital (New Delhi, India: Atlantic Publishers, 2008) 58. According to some researchers, television “may exacerbate isolation and thus play a role in the decline of trust.” Jeremy Adam Smith and Pamela Paxton, “America’s Trust Fall,” in Dacher Keltner, Jeremy Adam Smith, Jason Marsh, eds., The Compassionate Instinct: The Science of Human Goodness (NY: Norton, 2010) 207. [↩]

- On this concept, see Paul and Percival Goodman, Communitas: Means of Livelihood and Ways of Life (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1947). [↩]

- For more on this topic, see Courte C.W. Voorhees, John Vick, and Douglas D. Perkins, “‘Came Hell and High Water’: The Intersection of Hurricane Katrina, the News Media, Race and Poverty.” Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 17, no. 6 (November 2007): 415-429. I should also note that elitism is another obvious problem in getting to people to recognize their common humanity. I remember working as a union organizer in California universities in the mid-1990s, trying to get graduate student employees to join together for better wages and health care benefits. The greatest obstacle was convincing them to sign a card with the UAW emblem in the corner. I was often asked, what did an aspiring software engineer have in common with an autoworker? I should have flipped it around to ask: what sets apart the hard-working factory worker from the future cubicle slave? Little more than a smug fantasy of superior laboring. [↩]

- “Whether it wishes or not, television has become the principal mediation between the suffering of strangers and the consciences of those in the world’s few remaining zones of safety,” wrote Michael Ignatieff in a powerful 1985 essay about the ethics of presenting victimhood and suffering on television. “For if we cease to care, not merely about their fate, but also how their fate and our obligations to them are represented in our culture, then it is they—the victims on the screens—not us, who pay the heaviest price.” See “Is Nothing Sacred? The Ethics of Television,” Daedalus. Vol. 114, No. 4, (Fall, 1985) 76-77. This essay remains one of the most thoughtful explorations of compassion in the age of television. [↩]

- http://thinkprogress.org/economy/2011/02/04/173771/perry-children/ [↩]

- William Burns, Angela Yanuk, and David A. Snow, “The Cultural Patterning of Sympathy Toward the Homeless and Other Victims of Misfortune,” Social Problems 43:4 (1996) 391. [↩]

- I can recommend a few sources on the politics of compassion. Natan Sznaider’s The Compassionate Temperament: Care and Cruelty in Modern Society (NY: Rowan and Littlefield, 2001) which takes the contrarian position of associating compassion with modernity, whose alienating forces are usually thought to have weakened social bonds. Secondly, for a useful examination of compassion in political theory, in particular Rousseau’s championing of the concept, see Jonathan Marks, “Rousseau’s Discriminating Defense of Compassion,” The American Political Science Review, Vol. 101, No. 4 (Nov., 2007) 727-739. Finally, and most generally, see Dacher Keltner, Jeremy Adam Smith, Jason Marsh, eds., The Compassionate Instinct: The Science of Human Goodness (NY: Norton, 2010). [↩]

- I don’t mean to utterly discount the possibility of finding something that instills an “ethic of care” among reality programs, dramas, soap operas and other cable offerings; I simply am pointing to its relative rarity. [↩]

- You might even learn more in a few hours of so-called “serious gaming” that is designed to change the world, one byte at a time. For instance, see the game “Armchair Revolutionary” [↩]

- Media corporations will actively block dissenting views from their networks, even if you are willing to pay for airtime (Adbusters learned this the hard way when they repeatedly tried to purchase air-time for their “Buy Nothing” PSA). [↩]

- In her widely seen Ted talk, NBC Universal executive Lauren Zalaznick claims that television provides a national conscience that mirrors our social anxieties; she ends by thanking “the incredible creators who get up everyday to put their ideas on our television screens…” In some ways her bio says it all: “Now the tastemaker who brought us shows like Project Runway, Top Chef and the Real Housewives franchise is applying her savvy to the challenge of creating a truly multimedia network.” [↩]

- In Someplace Like America, his new book with the writer Dale Maharidge, the photographer Michael Williamson returned to some of the homeless people he had met in his classic documentary work in the 1980s. Noting the similarities between the suffering of the 1980s and the present time of “The Great Recession,” he wondered what we had learned collectively about the misery in our midst. “What’s the lesson?” he asked a family that had been homeless for years. “Are we our brother’s keeper?… We’re not ‘every man for ourselves.’ We won’t survive as a country if we keep that attitude.” John Winthrop couldn’t have said it better. In the age of electronic media, we may not need to visualize charity in order to become more charitable people—but it certainly wouldn’t hurt. See Dale Maharidge and Michael S. Williamson, Someplace Like America: Tales from the New Great Depression (Berkeley CA: University of California Press, 2011) 124. [↩]

- Stephen Pinker, The Better Angels of Our Nature (New York: Viking, 2011). [↩]

- David Brooks writes about “the limits of empathy” ; science reporter Benedict Cary takes a similar approach [↩]

- http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/04/science/04angier.html [↩]

- Some scholars might suggest that depicting suffering (or charity) is a poor substitute for (or even a distraction from) more meaningful forms of compassion. See, for instance, Saidiya Hartman’s Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997). Thanks to Scott Pryor for recommending this book. [↩]

Brilliant article! So needed. Let me first confess that I loved Aliens vs. Predators and was very excited to see the film you seem to disparage here… But that’s OK. ;-)

I wanted to add to this passage:

“But the prime mover in all this isn’t ordinary people whose tastes are mysteriously becoming callous, but an utter disregard for social ethics on the part of big media producers. Simply put, corporate television reflects an underlying economic system that is increasingly divorced from humane, democratic principles, if not basic human decency.”

I think it’s important to be honest about hegemony and its place in the cycle of production. You mentioned Marlon Riggs’ film not being found on cable, I agree and I think there are a few reasons why, least of which may be his call for compassion. Your article, seems to me, a wonderful complement to a few of the recent articles on FLOW calling for diversity in representation. Although these articles may focus on race, gender or sexuality, perhaps one of the results of truer, more diverse representations not beholden to heteronormative, white hegemony would be an engagement with more compassionate imagery. Economics is part of the issue here, but I think it is not the full story.

Randy,

This is a great essay – thank you so much for sharing this – I am especially struck by the suggestion, among others, that the solution is not to keep looking “compassionately”, as though simply training our sight on a subject will engender greater empathy and connectivity, but to refuse the passive audience model that media conglomerates so enjoy producing, and turn towards participation. The cruelty of vision, indeed…

What also interests me is how much this argument resonates historically in regards to television. The theater of suffering that critics began calling sitcoms in the ’50s and early ’60s certainly bespeaks an anxiety that TV, as soon as it was co-opted by General Electric and Phillip Morris, became an irresolute sphere of degradation, of excess, of exploitation. The keenest example I can think of in this era is Queen for a Day, in which housewives were paraded onstage by a former circus barker, and their sob stories and tears were measured on a “Clap Meter,” or how much the audience responded to their broken lives. As per usual in the purely competitive world of TV, only one “Queen” could reign. I’ve often wondered where these women went after the Lucky Strike ads took over the screen…

Thanks again.

Paul.

A very interesting read. I’m not sure there is very good evidence that we are in some sort of state of “pathological altruism” (and that this is a weird contrast with the harshness of life portrayed in various media). When the likely Republican presidential nominee, Mitt Romney, suggests that those who advocate a slight reduction in the favoritism of the uber-rich in government policy are waging “class warfare”, I don’t exactly feel any warm glow of healthy or pathological altruism.

Pingback: Faculty Research: Randy Lewis’ “The Compassion Manifesto” « AMS :: ATX

Although I generally agree with your arguments, I do think that you are misreading some of these cultural works, or giving them a short shrift, specifically when you claim that most reality television series allow viewers to unite in “aspirational solidarity” with the wealthy stars of the show. I would argue that many shows, such as Bravo’s Housewives franchise, the Rachel Zoe Project, Millionaire Matchmaker, etc. — really, a lot of the Bravo shows — are in fact helping viewers critique ridiculous amounts of wealth and conspicuous spending.

For instance, there was an uproar when one of the Beverly Hills housewives threw a $45k+ birthday party for her six year old, or when one of the women on the show claimed that her sunglasses were worth $25k. I really believe that eyes roll across America when these women talk about their charity events (because they do show this on television — quite frequently, actually) for children with cancer or women who can’t afford a wardrobe suitable for job interviews, and then step into their big, fancy Range Rovers to drive to their 4.8 acre estates in Malibu. I think a lot of the people watching these shows are actually excited about seeing and critiquing the Housewives’ lifestyles — they are not simply trying to emulate them.

However, by the same token, it’s really important to also address the fact that some of these women in the series are actually NOT that wealthy — in the Housewives of Orange County for instance, at least two or three cast members have gone through home foreclosure in the past few years. So, some of these shows really are demonstrating how the economy is failing, and maybe these strangers DO deserve our empathy, because they are going through tough times (which can even happen on television and in California).

Finally, though I definitely agree that there’s a horrible lack of programming about those who truly suffer, I would be hesitant to demonize what Bravo is doing. Isn’t it giving us a chance to laugh? To revel in the ridiculousness of dogs dressed up in costumes and carried around in purses? Isn’t that what some people need when you’ve gone to work all day or night (or can’t find work, for that matter)? Sure, this is still only for people who can afford the means to have a television, but nevertheless, can’t entertainment sometimes be just entertainment? Wasn’t it created as an mechanism for escape in the first place?

I really appreciate that this piece describes an absence in the current mediascape – in my own TV watching, I’ve felt that there has been a hole in the narratives we are able to consume, and perhaps what you point to comprises part of that hole.

At the same time, though, I wonder about who is actually responsible for the holes. Certainly corporate structures play a role, as you say, but aren’t they also simply giving audiences what we demand? Aren’t we guilty of craving and asking for (indirectly, perhaps, through Nielsen ratings and revenues from advertisements) the competitive freak shows that garner millions of viewers? One could make the claim, of course, that such a desire is engendered by an inherently competitive framework that trickles down from the Jack Donaghys of the corporate media world and seeps into our actual programming – but this is all fundamentally a two-way street. They are also responsive to what we want, and the people have spoken: it’s The Kardashians, The Situation and Snooki, and America’s Got Talent.

But maybe we’re also more complex than that. Maybe we watch Jersey Shore not because it offers a window onto real human experience, nor because we want to be the next Snooki or Situation, but because the show lampoons the human experience in a way that might, in some strange way, engender its own version of solidarity. Though there are undoubtedly many viewers who do aspire to GTL just like the Shore dudes and ladies, the absurdity put forth on that show is framed as “real” with a wink and a nod – we’re in on the joke of its production, even as we critique the cast. And, as a result, we can connect. We become woven into some broader social tapestry that can see beyond the hair gel to the inauthenticity of the show and the ridiculousness of the cast.

Perhaps this interpretation jibes in a way with what you critique – after all, community through nearly-universal disgust with a group of people is hardly a desirable means of evoking compassion – but there’s something to be said for how the audience actually reads these gladiatorial freak shows in a way that might knit us together in weird, unexpected ways.

Kat: I think you make a fair point on “Housewives.” There is more nuance within particular programs. I’m painting with a broad brush in trying to look at the overall flow, as it were, of the media torrent. Whether I glide over too many exceptions in my attempt to generalize, or whether these are relatively small number of exceptions, is a question for readers to decide.

On the question of “isn’t it OK for it to be escapist entertainment?” I’d say sure… but not at the expense of everything else. It’s akin to saying, If people like Big Macs and bourbon, then what’s wrong with that? Nothing in the abstract. But in the case of the big media systems, Big Macs are the only thing they’re able to get. Just like someone in small town TX who can’t get organic food but has a dozen fast-food franchises to “choose” from, many media consumers don’t have a “healthy choice” available to them. So it’s not the high-fat pleasurable escapist media that I object to–it’s the full-spectrum dominance that its achieved in many markets. I’m really looking for a more varied media ecology, one that is a little more accommodating of kindness and charity.

Carrie: You raise interesting points. I think that question of assigning blame is the hardest one. I do think I’m correct, but probably only partially so, in ways that you point toward. I think the form of an essay requires some streamlining, analytically-speaking, whereas the real story is probably something that requires book-length treatment. Yes, we are buying into the system in many ways, but I am still reluctant to say “the people are getting what they want.” I fear that this argument can justify whatever status quo emerges. If people like racist shows in 1960, or animal cruelty “crush videos” at some point in the near future (Tosh is getting close!), is that justified by virtue of popularity? After all, certain kinds of excellence are not rewarded in the marketplace—-this is why public radio and local coop radio is generally so much better than the big commercial radio stations. Still, the questions you raise are good ones and I appreciate your commentary.

Paul: thanks for pointing out the resonance with 1950s critiques—great insight.

Camillle: Yes, I’m with you. DIversity in every sense (cultural, ideological, affective) is what I’m hoping for, rather than a mediascape that is slanted towards particular outcomes (and relatively narrow ones).

Well, thanks for reading!

One P.S. regarding an essay that came to my attention after this piece was published: I would alert readers to Robert Hariman’s excellent “Cultivating Compassion as a Way of Seeing,” in Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, Vol. 6, No. 2. (2009), pp. 199-203.