Le Petit Mort: Toddlers and Tiaras and Economic Decline

Hollis Griffin/Colby College

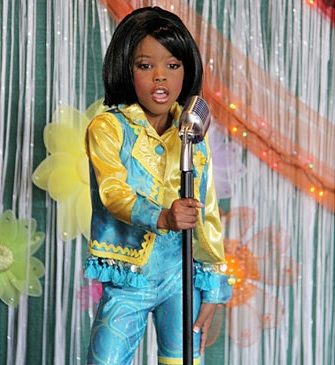

It’s hard not to watch Toddlers & Tiaras with a sort of sick fascination. The TLC reality program features a different “kiddie pageant” in each episode, following a handful of contestants as they prepare for competition and then “perform” for the judges. Plucked from elementary school to twirl and mug on stages at musty-looking Holiday Inns, Toddlers & Tiaras’ subjects are led through a gauntlet of training and cosmetic enhancement by their moms and a smattering of “pageant professionals”—hair and make-up people, specialized seamstresses, and voice coaches.

There are few things in the world more macabre than a nine-year-old girl with hair teased to the rafters, enough make-up to paint a house, and a “flipper” that masks her baby teeth with veneers. The mode of address on Toddlers & Tiaras positions viewers in opposition to the contestants and “pageant moms.” Interview segments reveal the hopes and dreams that parents have yoked to their children: not just success but fame, wealth, transcendence. Young contestants are routinely plied with sugar to keep their energy up, and they just as regularly fall asleep by the end of the episode. I end up feeling bad for them, even if they are frequently bratty and ill-behaved. (Wouldn’t you be angry if you had your eyebrows plucked against your will, and your skin buffed to a shade of Day-Glo orange?) But it’s the parents who often seem deluded—coaching sternly and loudly from the sidelines, expressing disappointment with their children in somber asides to the camera. In many episodes, parents refer to the pageants as “an investment,” articulating what is ostensibly an extra-curricular activity as a familial business decision that is expected to pay dividends at some later date. If children often symbolize futurity—the hopeful embodiment of “better things to come”—then Toddlers & Tiaras casts some harsh, ugly light on what’s coming next, both for American culture and maybe even capitalism, more generally.

On some level, it’s too easy to point to Toddlers & Tiara’s pageant moms as embodying feminine consumerist desire gone awry. Episodes frequently mention the astronomical costs of competing in kiddie pageants, and many of the pageant moms confess that participating in them is a financial hardship. Pageant moms frequently confess to fibbing about competition-related expenses to their husbands, and many others benefit from the financial support of doting grandparents. Toddlers & Tiaras details this feminine excess alongside a more subdued dialogue on class and economics. Watching the interview segments, it becomes clear that the parents of the pageant contestants are middle and lower middle class. Pageant moms are often homemakers, and their husbands are frequently factory workers, miners, small business owners. Thus, when an episode features a thousand-dollar, bling-encrusted dress for a six-year-old, it says as much, if not more about the parents’ class aspirations than the contestant’s performance of femininity.

Interview segments are introduced with a series of shots taken from the pageant contestants’ hometowns. Here, the program locates an overwhelming majority of pageants squarely in the Heartland; the settings include Sissonville, West Virginia, Salley, South Carolina, and Temple, Texas. Shots of sleepy Main Streets and grain silos lead directly to shots of the exteriors of the contestants’ homes. Many of these look forebodingly like the new “McMansions” at the center of the mortgage crisis. In Toddlers & Tiaras’ thinly veiled statement on American cultural geography, pageant frivolity is the domain of tacky flyover states, fostering viewing positions steeped in derision and scorn. By locating pageants, “flippers”, and aggressive moms in sleepy Heartland towns, Toddlers & Tiaras works like a lot of media representations of rural life—the Heartland “becomes the ‘other’ against which the ideal nation is defined by relief.”1 Via this logic, the hopes and dreams that pageant moms attach to kiddie pageants are as crazy as they are stupid: a downmarket pipe dream, a reckless financial gamble. With high participation costs and low prize money, “investing in” pageants seems as wise as buying a Hummer because one is worried about gas prices.

I experience a perverse glee and a deep melancholy when faced with the big hair and gaudy costumes on Toddlers & Tiaras. On the program, chintz and hairspray are objects of cathexis for the downwardly mobile. Pageant parents are often blue-collar workers, the very demographic whose traditional routes to the middle class—pensions, union memberships, federally subsidized student loans—are profoundly threatened by the current economic downturn and neoliberal thought, more broadly. No longer does a factory job, a union card, or a Stafford loan carry the promise it did for lower income wage earners in decades past. I see in many episodes of Toddlers & Tiaras anxious attempts to plan for the future via the labor of children. The hopes and dreams that parents attach to the kiddie contestants demonstrate a longing for safety and security at a point in history when those feelings are increasingly difficult to come by. When parents featured on the program attest to the pageants as a kind of “planning for the future,” the snark and cynicism that Toddlers & Tiaras so frequently elicits from me comes to a grinding halt. In those moments, the future embodied by the plucked and coiffed debutantes is neither rosy nor hopeful, it’s despairing, bleak—deeply, deeply sad.

I titled this column “Le Petit Mort” in an attempt to be cheeky. A French term that associates orgasmic release with death is somewhat apropos when talking about a television program in which girls are dolled up to look many years their senior, even competing in swimwear contests and lip syncing to Madonna songs. I’m not one for moral panics, and cultural anxieties about children’s sexuality are as old as modernity itself. The “little death” I see in Toddlers & Tiaras is different; it’s something specific to this moment in history. I see it in how the child pageant contestants symbolize the class aspirations of people whose economic opportunities are increasingly limited. In Toddlers & Tiaras, the glitz and glam adorning the girls indicate a future that, for many, will never come to pass. Of course, wistful optimism can be a sustaining force. But for every pageant mom who claims that the pageants teach contestants “life skills,” I can’t help but think that the energy, time, and especially the money they use to participate in them is better spent elsewhere. Maybe even something like language lessons so that the pageant contestants grow up speaking Spanish or Chinese or Hindi—better suited for a job market that is increasingly located elsewhere. Toddlers & Tiaras is evidence of the well-oiled capitalist machine of television, forever warning its viewers about proper modes of comportment and consumerism. If the program allows viewers to revel in excessive consumption and histrionic femininity, another of the program’s viewing pleasures is poking fun at the foolhardy dreams of others. It’s hard for me to feel good about that. Circulating amidst cries to dismantle what’s left of the welfare state, Toddlers & Tiaras is drenched in death—the twilight of the U.S.’s middle class, the sunset of economic development in the American Heartland, and, most pointedly, the uncertain future embodied by the little ladies in rhinestone-covered gowns.

Image Credits:

1. TLC.com

2. TLC.com

3. Screen Grab by Author

4. TLC.com

5. Screen Grab by Author

Please feel free to comment.

- Victoria E. Johnson, Heartland TV: Prime Time Television and The Struggle for U.S. Identity (New York: NYU Press, 2008): 5. [↩]

Bizarre, fascinating–some people are making a lot of money exploiting these deluded parents: those who hold the pageants, consultants, etc.

I think this is an excellent analysis, but I also wonder if these pageants have always been like this or if this reading of the parent’s anxieties is provoked especially by recent news and events. There were some earlier “behind the scenes” documentaries of these kiddie pageants, and most notably the whole thing was hyped by the Jon Benet Ramsey notoriety. Was this economic anxiety as evident then?

Are all contest shows open to this kind of reading, especially if we had more “behind the scenes” of Dancing with the Stars (the economic anxiety of second and third rate talent in decline?) or America’s Got Talent (can you really make a living off of diving into a kiddie pool from 20 feet?).

Time for a rerun of They SHoot Horses, Don’t They?

Thanks for the comments!

To answer your question, Chuck, I think that this particular reading is heavily predicated on the show’s use of establishing shots from the contestants’ hometowns. I know one of the documentaries you refer to — “Living Dolls” from 2000 or 2001 — and while there are definite parallels, I think that I’d want to see how the pageants are narrated spatially before I’d make too strong a connection. Also, ten years ago?? We’re talking about a much different moment economically speaking. So, yes and no — yes, there are some parallels but I’m loathe to make too much of them precisely b/c “T&T” is circulating at a moment when “down home Americana” just resonates so differently…….

I think I must admit to being an “academic” fan of T&T, meaning I hate watching it but feel compelled to for many of the reasons present in your analysis. I found this passage interesting- “But for every pageant mom who claims that the pageants teach contestants “life skills,” I can’t help but think that the energy, time, and especially the money they use to participate in them is better spent elsewhere. Maybe even something like language lessons so that the pageant contestants grow up speaking Spanish or Chinese or Hindi—better suited for a job market…”

I agree the show challenges us to engage with issues of class and I also agree resources are better spent elsewhere. The issue I see with the above prescription is one of cultural capital. When I watch the show and wish the parents were doing something “else” with their babies I “reflexively” (in the Bourdieusin sense) think, why? What in the experience of these parents makes language lessons in Hindi, Mandarin or Spanish valuable? The field/social arena of T&T is so divergent from the ones I navigate with my own children that my initial questions (and horror at the plucking, tucking, primping, poking, painting) fade to numbness. I watch this show and I don’t know what to do. It is, in its own way, wonderful fodder for nuanced engagement. Thanks for this article.

I love toddlers and tiaras!! I want to be a pageant girl, but my parents think only snobs are in them!!!! My dad wants a snob? That can be arranged!!!

FYI-

http://abcnews.go.com/blogs/en.....ly-parton/

The only issue I had with this piece was the last paragraph: it made me feel pretty horrible about myself. As a doctoral student in communication and media studies I often think I have a different lens through which I watch shows like this (along with anything the Kardashians or Housewives are on) that provides a critical distance rather than simply entertainment. It turns out that like TEEN MOM or 16 AND PREGNANT, this show is more about highlighting the sad lives of the lower middle class. Such a (media)ted view of this economic class allows us to distance ourselves from what we are watching rather than seeing the issue as systemic and thus, making us part of the problem.

Umm, whateves

Hollis,

Great piece! If we consider how for these parents, their children function as anthropomorphized lottery tickets, then all they need is that one event that will change everything. Nevermind the complexities of the lottery pay-out system, nevermind the realities and the difficulties of lots of income and no knowledge of how to make it last, or in the case of the pageant girls, what will happen to them if they ARE in fact successful or God help them, if they’re not. Thousands of dollars that they didn’t have in the wind is often the result. And, yes, I certainly take pleasure in my viewing classed superiority because I KNOW this whole game is a set up from the onset. No child wins anything from these spectacles. And all the parents gain is vicarious living through their lipsticked, teeth whitened babies.

@Samuel Jay: pardon my question, but I’m not sure I understand what you disagreed with about the last paragraph. I’m not even really sure what you were trying to articulate. Yes, we scholars in media studies do try to have critical distance but we also recognize that the notion of distance is not empirical nor is it objective and is absolutely informed by our experiences, tastes, preferences and other subjective interpretive knowledges. What is it that is so unclear about negotiated reading?

One thing I was left wondering is what kind of skills do the parents believe these competitions teach their children? Where do they see the pay off, or are the parents even able to verbalize this pay off? The reason I’m interested is because the obsession of the parents in these pageants reminds me of the recent discussions of “Tiger Moms,” or even just predominant parenting styles in China and Japan (not to make overgeneralizations, but I’m just referring to the cultural differences that are well known and discussed in popular culture). It is a similar obsession with making their children perfect and with the idea of a long term pay off, but one side manifests this obsession in music lessons, language lessons, math tutoring, SAT prep classes, etc. This discrepancy seems to be where the point of this article lies. It is a fantasy to believe that participating in this system of pageants will result in any real pay off for the parents; meanwhile their position in the economic structure of this country is being systematically undermined. It is very much like Kristen Warner mentioned: It’s like using lottery tickets for your retirement fund.

I would also argue that there has to be a connection between the physical beauty of the parents (often times not beautiful via the beauty norms of popular culture re: over weight) and their children. It’s like the parents invest all of their money to create this plastic version of beauty, which likely contributes to a substandard diet of more affordable and less nutritious foods. It is a rejection of what is natural for what is plastic. That may be the crux of the point about these pageants embodying capitalism. Capitalism doesn’t want to just sell you an apple; they want to sell you an apple injected with bubble gum flavoring. (as seen here: http://www.eatliver.com/i.php?n=7400) Capitalism does not profit from what is natural, they have to remarket it for public consumption. Thus, these little children are not valued for their natural beauty (baby teeth v. flippers), they purchase their beauty. I imagine, it’s serves as a vain attempt on the parts of their mothers to compensate for their own feelings of inadequacy.

I would like to post script all the above speculation with a disclaimer: I hate to make blanket generalizations about people I’ve not met, these are just some thoughts I have on general trends I have seen.

There is a fascinating photo-documentary project called Where Children Sleep. There is a four year old named Jasmine included in the work. The caption indicates she’s been in over 100 pageants. Her room juxtaposed against images of a mattress in the middle of a field (the sleeping place of another child) is an interesting complement to this article.

http://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/.....ren-sleep/

I heard a great paper recently at a reality tv conference in Dublin. The presenter did a great job of juxtaposing how the moms are presented as utterly deranged, while dads are edited as reasoned, some of them even pulling their kids from the pageants at the last minute.

One episode in the presentation was the “Trezured Dollz” episode in which the African American pageant director absconds with the contestants’s fees. I had to look up the episode on YouTube to further explore the race, including whiteness, issues. Alas, I was only left with Chris Rock’s voice echoing in my head. To paraphrase, a father’s (parent’s) only job is to keep their baby of the pole.

I was also intrigued by the comment about time and money being better spent learning Spanish, Chinese, or Hindi for employment in the global market, and that hits on an important point but not quite squarely. I think Brenda Weber’s book on Reality TV is right on–such shows are part of social pedagogy for instruction in a global economy that demands above all else semiotic alignment with normative gender and sex, which carry with them normative race, class, and national markers. Why? in part (but not all) if one can accomplish and display what these girls (or mothers) do, then a willingness to transform oneself in all other ways for the market follows, in the neoliberal model. Of course, some of us don’t buy gender normativity or these particular taste distinctions as evidence of marketplace expertise, but discipline for the market is key, no? I think a more interesting question is where on tv does the same instruction about discipline and alignment appear for different taste distinctions, aiming its pedagogy at upper middle class audiences? Mad Men?

Also, the mention of MTV’s 16 and Pregnant and Teen Mom in the same vein seems important. I agree these shows are about pleasure in the misfortune or dysfunction of “others”(schadenfreude), but there’s also identification and instruction for lower middle class and middle class women in the skill set they need to participate in the global economy, which means becoming “good” responsible mom-citizens who can take care of selves and kids and not be a burden on society (usually it’s about going back to school to find family supporting work). We know there is far more to it than this, but this gets the audiences to watch and buy everything needed for caring for and reinventing the self.

The focus on femininity is important and can’t be denied even if aca fans don’t like it–vast majority of reality tv focuses on women, according to Weber, and of course globalization has been built on women’s labor, arguably more than anyone else’s, in terms of pulling people in/around the world to work for very little.

Great piece Hollis!

Tonight, a few of us sat around chatting about ‘toddlers and tiaras’ and Britain’s answer – children cage fighters (I kid you not). The perversity of the latter is similar to the former but the involvement of the parents’ in the ‘sport’ are different. The fathers view their cage fighting sons (never in my life did I think I would write that phrase anywhere) to be tough kids with big promise. The mothers are nervous wrecks who do not condone the activity and seem resigned to leave ‘their boys’ to it. Given the economic downturn across Europe, I’m now left wondering less about the relationship from a strictly economic discourse (though it’s clear that those children competing in such events are being raised in a similar blue collar faction) but the representation of gender and sex roles in society as an outgrowth of change as a result of neoliberalism.

Hhhhmmmmm….

Hollis I came across this article and it immediately made me think of your article. I believe I have found something more macabre than a nine-year-old with hair teased to the rafters.

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/new.....t-8-9.html

Gary’s Loan Inc.

A Sincere and certified private money lender approved

by the GOVERNMENT. I give out international and local loans to all countries

in the world. Amount given out $2,500 to $100,000,000 Dollars, Euro and

Pounds, available now are Business, Personal, House, Travel and Student

Loans. Apply for a loan today with your loan amount and duration.Its Easy

and fast to get. 4% interest rates and monthly installment

payments.Check-out this great offer. For more information.

robertinc.linzer@gmail.com

I loved your article, very interesting.

By the way, in french, a synonym for “orgasm” is “La Petite Mort”, not “Le Petit Mort”, “Mort” being feminine.

Nice title for your article though, very creative.

I will admit that I have seen a few episodes of TLC’s Toddlers and Tiaras. The show is captivating – seeing the meltdowns of the little girls before they go on stage, the crazy ‘stage mom’ who clearly missed her chance to participate in competitions when they were younger, and the fathers who question how much the event is costing them and expressing how it is a waste of time.

I completely agree with Kristen that parents see their kids as a “lottery ticket”. They hope their kids will mesmerize the judges and they will win the top crown and cash prize. However, going into these pageants, the families usually spend more money than they would win back. The thousand-dollar dress, hundred-dollar tan and hair-do, and entrance fee is much, much more than the meager $500 or maybe $1000 prize.

Especially after their child does not place, the response is usually, “Oh well, we will win the next one”. This vicious cycle will seemingly never end.

It seems as if the children do not care much about winning. Any time they prepare for the pageant, they cry and yell about how they do not want to compete anymore. However, the parents still enter them, hoping that one day they will either win or be discovered by a talent agent. If anything, the kids are excited to be given their ‘special juice’ – an energy drink or soda that will help them be energetic for a few hours before crashing. Of course, this is horrible for the child’s health, but anything to help them win, right?

Pingback: My Hub Income | Personal Finance

It is very sad, that these lower class mothers, are totally uneducated and ignorant to the fact that they are ruining their children’s lives, and robe them from their childhood!! These pageans should be illegal!

With the current exposure on organized Child Sex Slavery, by politians, clergy, royalties, and the filthy rich, it should be every citizen’s Constitutional dury to protect the children!!!