How Long Will it Last, and Do You Really Own It?

Wheeler Winston Dixon / The University of Nebraska, Lincoln

Music, books, movies; they’ve all gone streaming, and it’s past the tipping point of being a fringe market. It’s THE market; it’s easy to access, requires no storage space, you can store your books, movies and music in clouds, and that’s all there is to it. As one proof of this, as of this writing, illegally streaming movies may soon become a felony, and by the time this appears, this may well be an accomplished fact. This also demonstrates, to me at least, that streaming is now the dominant technology, and corporations are taking notice; it’s where the money is. This new law alone should take down about half the videos on YouTube, many of which are complete films downloaded in 10 minute chunks, and which some of the readers of this column have previously suggested as a useful way to view classic films1. But the question for me is this: what do you really own? We’ve already talked about the various quality issues associated with streaming media, but what about an essential component (at least to me) of any purchase; possession of the physical entity itself? Of course, the concept is old fashioned to most; you simply watch movies on your iPad, listen to music on your iPod, and read books on your Kindle or Nook. But what do you really own?

An early harbinger of this was the now famous, and all too obviously ironic deletion of George Orwell’s novel 1984 , as well as Orwell’s Animal Farm, from Kindles around the United States by Amazon, when the company discovered they had accidentally uploaded an unauthorized version of the novel. As Brad Stone wrote at the time, on July 17, 2009 (light-years ago by today’s standards): “In a move that angered customers and generated waves of online pique, Amazon remotely deleted some digital editions of the books from the Kindle devices of readers who had bought them”2 An Amazon spokesman, Drew Herdener, said in an e-mail message that the books were added to the Kindle store by a company that did not have rights to them, using a self-service function. “When we were notified of this by the rights holder, we removed the illegal copies from our systems and from customers’ devices, and refunded customers,” he said. Amazon effectively acknowledged that the deletions were a bad idea. “We are changing our systems so that in the future we will not remove books from customers’ devices in these circumstances,” Mr. Herdener said.

But although Amazon has promised to make changes, the very fact that they possess such a technology; that they can simply pull books or anything else off your Kindle, or perhaps your computer, at will – truer now that ever if you use cloud storage – is unsettling. When you stream something, you don’t even get to keep a copy of the material; it’s just here, here, here and gone. You can, of course, copy streaming material as it passes through your electronic window, but most people don’t. As David Bowie long, long ago observed in a conversation with Jon Pareles– and gets megapoints for figuring this out before the rest of the industry twigged to it, and started demanding “360 deals,” covering all aspects of their merchandisability, from their performers –

“The absolute transformation of everything that we ever thought about music will take place within 10 years, and nothing is going to be able to stop it. I see absolutely no point in pretending that it’s not going to happen [ . . .] Music itself is going to become like running water or electricity [. . .] You’d better be prepared for doing a lot of touring because that’s really the only unique situation that’s going to be left. It’s terribly exciting. But on the other hand it doesn’t matter if you think it’s exciting or not; it’s what’s going to happen.”3

Just add movies and books to the mix and there you are; nailed. Whether you like it or not, here it comes. But one of the many problems attendant to streaming are the numerous cases of computers or software crashing when trying to access material, whether text, or video, or audio. If you own it, do you own it? Not if it’s streaming, or in a cloud that someone else controls. As someone who has used various cloud services to back up the contents of my computer, I’ve run into data corruption issues time and again, and have finally settled on hard drive back up right on site, so that I know I can access what I need even if the clouds go down, or the servers collapse. Netflix customers experienced this firsthand when the service crashed on June 19, 2011, denying customers the possibility of streaming content for several hours4.

And there’s also the issue of platforms; how many different sources of images are there, and who will win the war for commercial domination? Even as streaming technology moves into dominate the movie image market, there are those, such as Rocco Pendola, who question whether or not Netflix’s dominion is sustainable. Pendola isn’t an aesthetician; he’s a stock analyst. But his July 19, 2011 article on Netflix raises some interesting questions, starting with a blog post by Pauline Fischer, VP of Content Acquisition at Netflix. The post, dated July 17, 2011, and written in cheery corporatese, notes that:

“You may have noticed that Sony movies through StarzPlay are not currently available to watch instantly. This is the result of a temporary contract issue between Sony and Starz and, while these two valued partners work through their differences, we hope you are enjoying the wide variety of new movies and TV shows added daily. In the next few weeks, look for great movie titles like The Fighter, Skyline and Iron Man 2 as well as the first four seasons of Mad Men, all to watch instantly.”5

As Pendola comments, “Of course, there’s always more to the story. Later on Friday, the Associated Press reported the news, adding the following: A person familiar with the matter said Netflix’s explosive subscriber growth triggered a clause in Sony’s agreement with Starz that resulted in the stoppage. The person was not authorized to speak publicly and requested anonymity. Of course, that’s a pretty vague statement. It’s not easy to figure out exactly why “explosive subscriber growth” would result in Sony pulling its content from the Starz deal. One possibility could involve a Sony initiative that does not get too much attention, at least relative to Netflix, Hulu, YouTube (GOOG), and the various TV Everywhere platforms – Crackle. Crackle offers free-of-charge streaming access to various Sony-owned movies and television shows [ . . .] In Sony’s case, why allow Starz to reap the rewards of picking Netflix’s pockets while the $8-a-month Netflix service continues to dilute your programming to an ever-expanding subscriber base?”

With Disney and Time Warner in the wings planning to open similar operations, this is a good point. And then there’s this final thought to consider; when a film is digitized, it requires constant maintenance, and transfer to new platforms, in order to continue to exist, as demonstrated in a report entitled “The Digital Dilemma,” commissioned and executed by the science and technology council of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Milton Shefter, a pioneering film archivist, and one of the authors of the report, notes that despite its pristine visual quality, the digital image is inherently unstable, constantly in a state of flux, and that storage of digital imagery is a never-ending process of maintenance and upgrading. As Michael Cieply noted in The New York Times, “To store a digital master record of a movie costs about $12,514 a year, versus the $1,059 it costs to keep a conventional film master. Much worse, to keep the enormous swarm of data produced when a picture is ‘born digital’ – that is, produced using all-electronic processes, rather than relying wholly or partially on film – pushes the cost of preservation to $208,569 a year, vastly higher than the $486 it costs to toss the equivalent camera negatives, audio recordings, on-set photographs and annotated scripts of an all-film production into the cold-storage vault”6

As David Bowie noted nearly a decade ago, there’s no stopping the streaming parade. But the convenience factor aside, it’s easy to see that the rush to streaming creates many new ways to “monetize” back catalogue images, music and books, in a way that perpetuates the consumer’s dependence on the supplier, and makes sure that there will be a constant revenue stream not only to access, but also to store, download, or view the works you have supposedly “purchased.” Once upon a time, about a half century ago, you bought a television, stuck an aerial on the room, and although you had to put up with commercials interrupting your viewing, what you got after that was free. Now, you get the commercials, and you have to pay for the content, on cable, or on the web.

Once, you bought a record or a CD, and you put it on the shelf, and it was yours to keep forever. You bought a DVD, and you could always access it by simply picking it out of your library. Now, you’ll have to pay for everything again and again and again, with no assurance that what you had on file yesterday will be there tomorrow. Further, as Heather Hendershot commented after my first column in Flow, “Some Notes on Streaming,” once a film goes “streaming” on Netflix, they delete that title from their DVD collection; why bother with physical inventory when you have a digital copy? If you think of Netflix, therefore, as a library you can reliably borrow from, you’re in for a shock. As Bowie pointed out, “it doesn’t matter if you think it’s exciting or not; it’s what’s going to happen.”

Now it’s happened, and while it may be exciting, it’s also expensive, transient, and takes the consumer into a new and interesting place; you don’t own what you buy, and you have to pay to store it, and also to connect to it. And it will cost more, and have more commercials, everyday.

What will happen next? Stay tuned.

Image Credits:

1. Can anyone really own Spock?

2. Do we really own the content we buy for our devices?

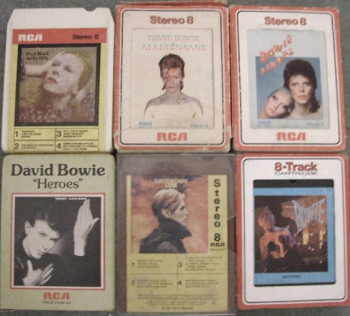

3. An example of David Bowie’s “Merchandisability?”

4. What happens when the Bowie 8-Tracks cease to exist?

Please feel free to comment.

- Fiegerman, Seth. “Streaming Film Illegally May Soon Be a Felony,” The Street, June 20, 2011. Web. [↩]

- Stone, Brad. “Amazon Erases Orwell Books From Kindle,” The New York Times, July 17, 2009, Web. [↩]

- Pareles, Jon. “David Bowie, 21st-Century Entrepreneur,” The New York Times, June 9, 2002. Web. [↩]

- Palazzo, Anthony. “Netflix Restores Website, Streaming Service After Outage,” Bloomberg News, June 20, 2011. Web. [↩]

- Fischer, Pauline. “Temporary Removal of Sony Movies Through StarzPlay,” Netflix Blog, June 17, 2011. Web. [↩]

- Cieply, Michael. “The Afterlife Is Expensive for Digital Movies,” The New York Times December 23, 2007. [↩]

A similar thing seems to be happening with computer software: Adobe is trying to get everything on a subscription model so you pay a monthly fee to keep using software. They claim they will be able to keep tweaking the software all the time, but it also means they have a steady stream of income from a program, not just a bump up when they come out with a new revamped version. In the long run you pay more, and keep paying and paying. Kind of like leasing a car instead of buying one.

One facet I’d add to your excellent discussion is the place of public and academic libraries. In the US at least, libraries have been able to function due to copyright principle of “first sale” – once you purchase a physical object like a book or DVD, there is no restriction on you re-selling, renting or lending it. Thus libraries have been able to fairly inexpensively create a vast collection of content, much to the dismay of many publishers (who have long wanted a way to “monetize” that access). But in a digital stream, there is no first sale, as every time you access a stream you are technically “copying” the content onto your device. Thus once streaming or e-copies become the default, library access will become subject to license agreements or ongoing costs – and ask your local librarian how such arrangements with serial titles are working out for them! Sadly, a stable and accessible collection of content in an era of library budgetary squeezes is going to become a rarity.

I’ve been following this series of articles eagerly — really good stuff about very timely questions. I’m wondering if there’s a use-value question here, though? For instance, physical objects require storage places. The physicality is a problem if you have a small apartment, move a lot, etc. I’m thinking also of work by Lynn Spigel, Anna McCarthy, Derek Kompare, and Kyle Barnett that talks about problems endemic to situating technology in space. What if you’re just as happy to watch it once and get rid of it b/c the thought of having to box it up and move it is daunting? (I’ll claim to be one of these people….) So, to relate this to use-value — what if the use-value is in the one-off and not in the perennial access?

Setting aside technological/material questions for the moment, and focusing instead on the issue of ownership and possession…

Experientially, how is streaming all that different than going to a movie theater? One does not “own” anything there, but rather rents time in a chair with flashing lights in front of your eyes. It seems to me the concern about streaming is a reaction to the logic of objectification and personal ownership that was made commonplace by DVD and, to a certain extent, videotape before it.

Thanks for all your comments! Chuck, I agree with you completely; constant updates, continual drain on one’s checking account. Jason, the library issue is a real one, and has yet to be really addressed. Hollis, yes, storage is a problem, and we just threw out a raft of VHS tapes, but Dan, the problem with streaming, yes, is that you don’t own it — yes, it’s analogous to a movie theater, but the theatrical experience is far superior to what you get on the home screen. But most importantly, when we threw out the VHS tapes, we replaced them with DVDs, because I want to make sure that — DVD rot issues and other concerns aside — I own certain films and be sure I’ll be able to find them in hard copies, without streaming glitches, for use in my work. So when I see a film I like a theater, I immediately order the DVD for permanent storage. And yes, I have an attic full of 10,000 DVDs and about as many hardcover books. I just don’t trust Netflix to have these films always available.

Just posted this on my blog:

In a post on The Wrap by Brent Lang comes the news that Netflix has now split into two companies, Netflix and Qwikster; Netflix will handle streaming, and Qwikster will rent DVDs. But by splitting the company in two, Reed Hastings has diluted the brand name, which can’t be a good idea, and more or less separated customers into two groups; those who stream and those who don’t. Since there’s no reduction in the recent price hike, I really don’t see the point in this. I think it will just annoy people further, and add confusion to the mix, as well.

As Lang writes:

“Netflix CEO Reed Hastings admitted Sunday night that the company fumbled its handling of recent price hikes to its most popular subscription packages. However, the embattled home entertainment chief stopped short of scrapping the higher costs. Instead, he said the company would split its DVD-by-mail business from its streaming service and re-christen it Qwikster. So basically, Netflix keeps its unpopular price increase and will now force customers to subscribe to two separate services in place of one. Talk about a cup of salt with that tablespoon of sugar.”

I just don’t understand this; take a reliable, popular, highly successful service, then up the price by 60%, then split it in two, but still keep the price hike? This makes no sense to me at all.

Here’s Reed Hastings own explanation for the move, as posted on the company blog, which reads in part:

“Many members love our DVD service, as I do, because nearly every movie ever made is published on DVD, plus lots of TV series [emphasis added; not true, there are hundreds of thousands of films not available on DVD]. We want to advertise the breadth of our incredible DVD offering so that as many people as possible know it still exists, and it is a great option for those who want the huge and comprehensive selection on DVD. DVD by mail may not last forever, but we want it to last as long as possible [emphasis added; translation, “we may not offer DVD rentals much longer, after having killed off all the mom and pop brick and mortar stores in the United States, but we’ll create this separate business to bring DVDs to a quick demise, so we can concentrate on streaming, which is why we’re keeping the Netflix name for that].

I also love our streaming service because it is integrated into my TV, and I can watch anytime I want. The benefits of our streaming service are really quite different from the benefits of DVD by mail. We feel we need to focus on rapid improvement as streaming technology and the market evolve, without having to maintain compatibility with our DVD by mail service.

So we realized that streaming and DVD by mail are becoming two quite different businesses, with very different cost structures, different benefits that need to be marketed differently, and we need to let each grow and operate independently. It’s hard for me to write this after over 10 years of mailing DVDs with pride, but we think it is necessary and best: In a few weeks, we will rename our DVD by mail service to “Qwikster.”

Good luck with that!