Accessing Historical Documentaries in the Convenient Digital Age

Heather McIntosh / Boston College

Today’s multi-media environment features an abundance of documentary programming easily accessible through a variety of means, including broadcast television, cable, satellite, DVD, online streaming, and video-on-demand. To use a more-encompassing definition of the term, this documentary programming includes docusoaps, gamedocs, and other forms of reality shows; nature shows; investigative and other news reports; how-to or DIY programs; and social issue explorations.

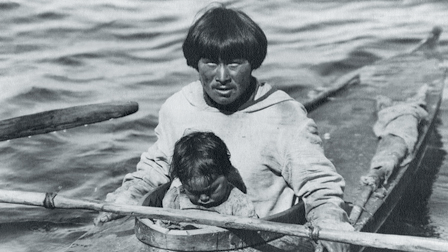

Nanook of the North showed in theaters during the early 1920s. It drew so much attention that its director, Robert Flaherty, got a deal with an emerging film studio to make “another Nanook.”

This convenient access to documentary is a more recent development in terms of documentary distribution. Unlike Hollywood studio-backed fiction films, documentary films never gained uncomplicated access to theaters and theatrical audiences. Robert Flaherty’s classic Nanook of the North got shown in some theaters through distribution by Pathé Exchange and garnered enough critical attention to get Flaherty an offer to make another similar documentary, but few, if any, other documentary makers at the time saw a similar level of success. Movie theaters offered one exhibition outlet for documentary film, other outlets included (and still include) museums, art houses, festivals, educational settings, book stores, and other community spaces.

The then-new medium of television brought a new outlet for documentary media. In the early days of broadcast television, particularly the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Big Three networks showed some documentaries, including such canonical works as Harvest of Shame (CBS, 1960) and Hunger in America (CBS, 1968). This period for early broadcast television documentary remained brief, and entertainment programming dominated their schedules. Documentary did find an outlet with the newly launched Public Broadcasting Service in the early 1970s, and the service remained the key broadcast home for documentary into the 1970s and 1980s, when the growth of cable programming really took off. Basic cable channels built their program line-ups around documentary media, and pay cable channels, particularly HBO with its documentary division, integrated documentaries into their schedules as part of their prestige programming.

Today’s media convergence environment brings programming into a whole new environment full of options for audiences to access documentaries and other content. Along with broadcast, cable, theaters, and DVDs, audiences use Web sites such as Hulu, Netflix, and SnagFilms. Instead of limiting access to one or two media, some outlets maximize the multimedia options. PBS, for example, sometimes uses a combination of broadcast, online streaming, and an iPad application, along with a DVD purchase option.

A significant portion of this documentary programming available through these multimedia means are recent productions. These productions are usually among the more popular ones that gained attention through festivals such as HotDocs or Sundance, which resulted in them getting picked up by more mainstream distributors.

But what about consistent online access to older programming? Frequently, older, fiction-based programming is more readily available for online access than documentary programming. For example, the classic Star Trek series, I Love Lucy, Perry Mason, and Dynasty are available for viewing online through CBS. For another set of examples, Hulu offers The Donna Reed Show, Alfred Hitchcock Presents, and even 170 episodes of Green Acres.

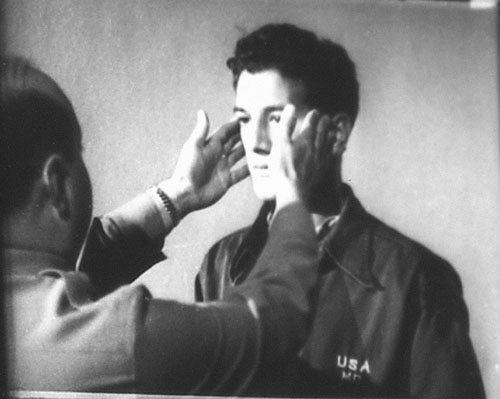

John Huston’s Let There Be Light (1946) was shelved by the Army for 40 years before audiences were allowed to see it. Now that the piece is in the public domain, it is available for download through archive.org and for viewing on other sites.

Older documentary programming proves a little more elusive. Some older titles are available through Hulu and Snagfilms, but the term “older” here still refers to many titles within the last 30 years or so. Some titles appear on YouTube, but the question remains of their potential copyright violation. One resource for some older documentaries is archive.org, which brings together titles from the Prelinger Archives, the National Archives and Records Administration, and other diverse sources. Finding some documentary classics there takes a little digging, but the online archive does include John Huston’s Report from the Aleutians (1943), The Battle of San Pietro (1945), and Let There Be Light (1946), just to name three.

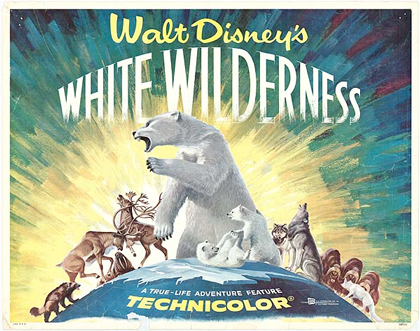

Several issues might influence the availability of older documentaries online. One issue relates to public domain and copyright. Public domain titles face no restrictions in terms of making them available online, at least outside the labor to convert the titles to digital form and to upload them somewhere. Let There Be Light, for example, belongs to the public domain. Copyright creates complications, as corporations have found ways to extend copyright lengths again and again, thereby preventing titles from becoming part of the public domain and thus becoming more easily accessible. Disney’s White Wilderness (1958) offers a great example of early nature documentary and of excessive manipulation, as the makers staged the now-popular myth that lemmings commit mass suicide in order to create more interest. For now, White Wilderness remains available for online streaming through Amazon.com, but what happens when Disney pulls the online rental option?

HBO’s fictionalization of the making of An American Family brought some attention to the PBS reality series. Pictured are James Gandolfini as Craig Gilbert, Diane Lane as Pat Loud, and Tim Robbins as Bill Loud.

Another issue might lie in the perceived lack of interest among audiences. While documentary carries with it some cultural significance, it sometimes also comes with an unfortunate reputation of being “boring.” Older documentaries in particular bear this misapplied stamp, often because of their overbearing voiceover narration and strong didactic overtones. But this supposed lack of interest might also be connected to a lack of awareness. Most of media content today features this year’s documentaries, with even last year’s titles quickly becoming part of the collective forgetting. Some moments do reignite some interest in historical documentary, such as HBO’s Cinema Verite, which is a fictionalization of the making of the PBS reality series An American Family, but remakes of fiction programming occur much more frequently that “fictionalizations” of documentary. Either way, though, media “history” remains entrenched firmly in the present while at the same time forgetting the past.

The third issue is money. Many online distribution systems rely on advertising, either banner or in video, to support themselves, while others rely on subscription or rental fees. The questions here center on if these older documentary titles would generate interest and draw in viewers.

The Topp Twins: Untouchable Girls received a warm welcome at its North American debut but otherwise struggled to get distribution there. How will online distribution affect access to these films a decade or more after their release?

All of these reasons come back to some underlying questions that offer no simple answers. One, as more people watch through multimedia devices and online streams, what happens to the selection? We have more options for accessing programming, but what kinds of programming are we getting access to? In ten years, Michael Moore’s films likely will still be available, but what about titles such as The Topp Twins: Untouchable Girls (2009) or Tongues Untied (1989)? From there, is there a way to curate and organize historical documentary online so that audiences have access to that history and so that it gets preserved as well?

Please feel free to comment.

Image Credits:

1.) White Wilderness

2.) Nanook of the North

3.) Let There Be Light

4.) HBO’s Cinema Verite

5.) The Topp Twins: Untouchable Girls

Thank you for the article, you make some good points.

What I like about older docs is the way in which you can see what counted as ‘realistic’ and ‘true’ at the time of production and exhibition.

In the current economic climate, partnership with a for-profit media company might be one way to curate docs online, that would help get around any financial obstacles due to copyright. But then you’d have to deal with the problems of generating profits and the possibility of censorship.

Pingback: Writing Elsewhere | Documentary Site