Garbage Collectors

Scott Webel / Museum of Ephemerata

Ephemerata Gardens collects all kinds of objects and life forms.1 Some are added on purpose, and others move into the landscape patch of their own volition. Collecting is a process whereby a habitat temporarily gathers things together in a net of emergent relationships. Sometimes a sorting mechanism aggregates collections by size, weight, composition, or information content. Other times everything is anarchically roiled and churned. Shiny silver candy wrappers and Styrofoam cup shreds blow into the yard from the alley. Nesting blue jays drop six-pack rings. A plastic grocery bag parachutes from the sky onto the tomatoes.

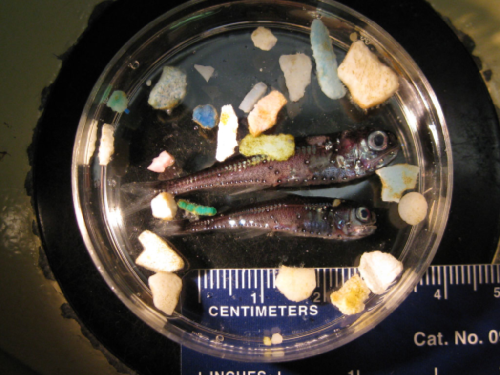

Once released into the world, anthropogenic garbage has a life of its own, forming unanticipated collections and connections. The North Pacific Garbage Gyre (or Garbage Patch) is a museum of plastics gathered by the clockwise vortex of oceanic currents. Four other gyres spin in the South Pacific, Indian, and North and South Atlantic oceans. These liquid landfills are self-aggregating collections of trash thrown off ships and set loose by cities along coasts and rivers. Over the decades, plastic photodegrades into ever-tinier polymer chains nicknamed “mermaid tears.” Surface water from the Pacific Gyre’s heart consists of up to six parts plastic to one part plankton by mass.2 Plastic bonds with persistent organic pollutants like DDT and PCBs. While bigger pieces of plastic accumulate life forms like bristle worms, crabs, anemones, and barnacles, smaller pieces like mermaid tears and plastic bags get mistaken as food and eaten, presumably concentrating toxins up the food chain (to humans). Fish stomachs can turn into plastic garbage collectors that eventually kill them if fishermen don’t get them first.

A garbage gyre’s size is hard to establish. Journalists have reported the North Pacific Garbage Gyre as being twice the size of the United States, twice the size of Texas, and only 1% the size of Texas. They are often referred to as “islands,” although they are much more diffuse, a barely visible “plastic soup.” The gyres also exist in an uncertain temporal scale, with today’s single use plastics becoming the next decade’s (or century’s, or millennium’s) mermaid tears. They are colossal archaeological objects, like the sky. The gyres’ tendrils touch remote beaches and compose the bodies of jellyfish. Maybe part of one is in your hands, right now.

Garbage gyres spin out of cities with a catastrophic surplus of threat that sucks us all into their centers. Nobody knows much about them, so urban legends and apocalyptic media reports run wild. They are one half eco-catastrophes begging scientific research and political mitigation, and one half mythological monsters preying on our fears of causing ecological collapse. In a flash, questions like “are humans killing the oceans?” throw together an anxious “we” paralyzed by the staggering size of the accident and the guilt-ridden momentum of consuming plastic every day. The gyres swirl in our minds as forms of collective worry.

Since 1997, Captain Charles Moore with the Algalita Marine Research Foundation has led multiple visits to the North Pacific Gyre, including a 2011 voyage that tourists and researchers could join for $10,000 a head. In 2008 a three person crew from VBS.tv joined Captain Moore to film an hour long documentary that aired on MTV2 and online. The weeklong sailing trip to “nowhere” takes its toll on the three mid-twenties documentary-makers as they deal with boredom, seasickness, and a claustrophobic lack of privacy in which Moore is cast as “Dad” in an Oedipal drama. A sense of damnation haunts the film crew as they haul up ghost nets3 and swirl around jars of mermaid tears while moodily narrating their firsthand experiences of oceanic plastic pollution:

I’m totally bummed… It’s different to see … a picture of a jar somewhere, like some magazine, then to realize how long it’s taken for us to get here. I mean we are in the middle of nowhere. I think there are so few people who have actually been here. Maybe no one has ever been in this spot… and it’s filled with our trash, you know? We have really screwed up. We’re all going to hell.

Captain Moore takes them to hell’s center, where they expect to bear witness to a trash island as far as the eye can see, but there is nothing but the usual stray plastic and a higher concentration of invisible mermaid tears.

Call in the artists to give some kind of sensible form to the diffuse plastic monster! Recent artworks respond to garbage gyres by raising awareness and critical self-reflection. Among them, the Institute for Figuring’s “Toxic Reef” is a coral reef collaboratively crocheted out of plastic bags. Kim Holleman’s “Trashnami!” assembles the gyre as a wave crashing down on us. Chris Jordan’s photo series “Midway” documents albatross corpses stuffed with plastic objects, and “Gyre” (after Hokusai) is a mosaic made out of materials collected in the North Pacific. The photogenic horror of these art works gives environmental groups like 5 Gyres aesthetic leverage in their campaigns to regulate plastic production and altar our habits of mass consumption. A flood of online videos about the gyres mixes images of ugly beauty with the aesthetics of scientific research as technicians fiddle with their microscopes, filters, flasks, and tweezers.

The gyres themselves are diffuse mosaics of toothburshes, cigarette lighters, fragmented water bottles, monofilament rope, and other ordinary objects. Are these garbage patches as toxic and deadly as our collective secular apocalyptacism likes to imagine? Even as they strangle and mangle large aquatic animals, ghost nets can become little floating islands of life. One team of oceanographers researching plastic pollution’s impact on microorganisms found that “photosynthetic microbes were thriving on many plastic particles, in essence confirming that plastic is prime real estate for certain microbes.”4 The polluted gyres, yet another indictment of the “human domination of earth’s ecosystems,”5 double as nonhuman cities of living garbage. To “clean up” the patches with endless trawling would also be to kill all the life forms that, however improbably, claim the patches as their natural habitats. The gyres also offer green capitalists and social enterprises an opportunity to flex their muscles and show off. Method, a non-toxic cleaning products manufacturer, markets a 100% recycled bottle, a quarter of which is made from plastics intercepted from beach clean up projects.

I look around Ephemerata Gardens at the plastic menagerie that, some day, will split and crack to shreds. The cat from New York’s Chinatown , the classic kitsch pink flamingos, a donkey from the Cathedral of Junk garage sale, a thrift store carousel horse, a bodiless doll from Smut Putt Heaven. Some day at least a little bit of them might flow out of Austin down the Colorado River to the Gulf of Mexico and gather with the other plastic in the North Atlantic Garbage Gyre.

Image Credits:

1. “Three Gyres,” photo by 5Gyres, 2010, http://www.flickr.com/photos/5gyres/4593934842/.

2. “Rope Debris,” photo by J. Leichter for SEAPLEX (Scrips Environmental Accumulation of Plastic Expedition), 2009, http://www.flickr.com/photos/8581704@N02/3856010901.

3. “Gyre,” by Chris Jordan, 2009, http://www.chrisjordan.com/gallery/rtn2/#gyre.

4. “Lanternfish and Plastic,” photo by SEAPLEX, http://www.flickr.com/photos/8581704@N02/3818175490/.

5. “Bodiless Doll,” photo by the author.

Please feel free to comment.

- This is part of a larger online writing project, “The City of Living Garbage,” a guidebook to my backyard. [↩]

- C.J. Moore, S.L. Moore, M.K. Leecaster, and S.B. Weisberg, “A Comparison of Plastic and Plankton in the North Pacific Central Gyre,” Marine Pollution Bulletin 42 (2001): 1297–1300, ftp://ftp.sccwrp.org/pub/download/DOCUMENTS/AnnualReports/1999AnnualReport/10_ar11.pdf. [↩]

- Ghost nets are tangled masses of fishing gear lost or abandoned at sea. [↩]

- Oregon State University News & Research Communications, “Oceanic Garbage Patch Not Nearly as Big as Portrayed in Media,” 2011,

http://oregonstate.edu/ua/ncs/archives/2011/jan/oceanic-“garbage-patch”-not-nearly-big-portrayed-media. [↩] - P.M. Vitousek, H.A. Mooney, J. Lubchenco, and J.M. Melillo, “Human Domination of Earth’s Ecosystems,” Science 277, no. 5325 (1997): 494-499, http://www8.nau.edu/envsci/ENV330website/ENV330/downloads/VitousekHumanDomination.pdf. [↩]

Fantastic piece.

Pingback: Selectism's Favorite Stories from Around the Web | Selectism.com

Pingback: Selectism | Around the Web | Ashton Kusher