Flow Favorites: “We Think INSIDE the Box”: CD Box Sets in the Download Era

Kyle Barnett / Bellarmine University

Every few years, Flow’s editors select our favorite columns from the last few volumes. We’ve added special introductions and included the original comments to the piece below. Enjoy!

Flow editor Paul Gansky:

Media studies often privileges discussions of representation over other forms of study. Kyle Barnett’s article, “We Think INSIDE the Box,” is an illuminating argument of why things matter as well. Taking CD and DVD box sets as his subject, Barnett suggests that there is a desire – and a market – for tenable, provocative, imaginative objects that pay tribute to the artistry of a musician or a filmmaker. He additionally incisively shows that a song, or a film, is not simply a commodity to be plugged into the fastest and most immaterial forms of distribution available. Rather, recording and sharing these media are crucial forms of cultural preservation, which have historically been (and should continue to be) expressed in packaging. Plus, where else on Flow would you get a chance to see blues guitar icon Charley Patton rub shoulders with gospel singers and Stan Brakhage, all strung together with bits of raw cotton and cedar?

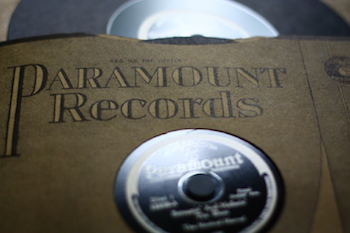

In 2001, Revenant Records, a small Austin, Texas label, released Screamin’ and Hollerin’ the Blues, a seven-CD box set chronicling Delta Blues legend Charley Patton.1 The set included all known Patton sessions between 1929 and 1934, a hardcover “78 [rpm] album” in which compact discs were stored, a reprint of John Fahey’s 1970 book on Patton, plus 100 pages of “exhaustive new writing,” reproductions of Paramount Records’ advertising for Patton releases, and a “complete Paramount/Vocalion Record Label Sticker Set.” A few years later, Revenant released Holy Ghost, a nine-CD set of “rare & unissued records” by free jazz saxophonist Albert Ayler, including a full-color hardbound book with essays by Amiri Baraka and others, “artist testimonials of first encounters with Ayler’s music,” and more, all contained in a “lavish Spirit Box…cast from [the] hand-carved original.” Included in the box is a pressed flower, a forget-me-not, perhaps a message to jazz fans regarding Ayler’s legacy. How does one critically evaluate this kind of unprecedented, even excessive packaging?

Not to be outdone, Atlanta’s Dust-to-Digital introduced their label with Goodbye, Babylon, a six-CD box set of 135 songs and twenty-five sermons, a 200-page book that includes Bible verses, lyric transcriptions, and liner notes giving historical context for each recording. Perhaps the most unusual touches of the package are the materials used, as detailed on the label’s web site. The contents are “reverently packed with raw cotton and housed in a deluxe 8” x 11” x 2.5” cedar box.” Dust-to-Digital defines their mission as producing “high-quality cultural artifacts, which combine rare, essential recordings with historic images and detailed texts describing the artists and their works.” A growing number of small music labels have quietly created innovative niches by pushing the limits of the traditional CD box set through the creation of lavish packages unprecedented in their appeal to music fans, scholarly attention to detail, and aesthetic excess, in an attempt to cultivate a record collector culture that has long been part of recorded sound’s societal circulation. The company slogan of Susan Archie’s World of Anarchie, which designed each of these box sets, is “we think INSIDE the box,” a strong statement as the CD format’s popularity wanes.2

What might these lavish CD packages suggest about the recording industry’s marketing in their specific appeals to consumers and collectors? What might the trajectory of production and consumption in recorded sound culture suggest about similar practices regarding film and television packages in the DVD market?

For the film and television industries, a new collector culture rose with the popularization of laser discs, videotape, and DVD technologies.3 Research on the DVD’s impact on film and television has convincingly mapped this technological, industrial, and cultural shift. Chuck Tryon suggests that film DVDs’ emphasis on extras and “insider” knowledge invites the home viewer into “discourses of cinematic knowledge or connoisseurship.”4 As Derek Kompare writes about TV collections on DVD, “People have long been regarded in media studies as ‘spectators,’ ‘viewers,’ and ‘audiences,’ but much less so as ‘users,’ ‘consumers,’ and ‘collectors,’ as television moves from what Bernard Miège sees as a move from “a logic of flow to a logic of publishing.”5 While visual media studies’ “collector’s turn” marks an important transition, it has come at a paradoxical moment. With the advent of audio file distribution, recorded sound as a medium seems to be abandoning the recording industry’s object-based past, at least in part, just as the film and television industries discover it.6

At present, both visual and aural media circulate in somewhat similar collector cultures, despite some differences. While film and television DVD packages carry increasing amounts of content, most leave the “extras” to the disc themselves.7 The greater storage capabilities of DVD have likely encouraged this practice. This may also have to do with differences in what counts as “extras” in CD vs. DVD box sets. DVD extras have largely remained focused on disc-based extras (deleted scenes, commentary tracks, “easter eggs”). With contemporary movies, these extras are created with the DVD package in mind. Compare this to many CD box set collections, particularly those that reference much earlier eras of recorded sound. Those packaging the music, collectors, enthusiasts – they are often recontextualizing secondhand. Often those working on these box sets are dealing with a finite amount of original recordings (how many Charley Patton recordings are known to exist?). These figures can also be somewhat marginal with the passing of time, which may require extensive archival research. This issue makes both the creators of such box sets into armchair music historians, scholars and aesthetes. This amount of work in collecting various materials and packaging them for sale encourages the producers of such box sets to see their audience in much the same way. In fact, it is relatively common for record collectors, music fans, and historians to supply materials for these releases, as is the case for each CD box set I mentioned above.

Of course, the Revenant and Dust-to-Digital box sets point to a long history of record collecting. In many ways these releases share an ancestral lineage with Harry Smith’s three-LP reissue package of commercial blues and country recordings that date from the 1920s and 1930s. Released by Moe Asch’s Folkways label, Smith conceived of his anthology in fundamentally different ways than those common to other Folkways releases. While he tried to introduce and illuminate on the one hand, he also tried to mystify and confuse with the other. This latter dynamic is evident in Anthology’s artwork, which features collages referencing ancient notions about the power of music and the mystical origins of music in the “celestial monochord.”8 Smith’s project points to these later releases as a way to attract new listeners to relatively obscure figures in musical history. To borrow Roy Shuker’s phrase, Smith’s project was an act of “cultural preservation” as well as musical enjoyment.9 This added dynamic at work in these CD box sets – cultural preservation projects as well as commercial products – also point to a more ephemeral relationship at work in the recording industry and its relatively low barrier to entry.

Contradictory developments impact CD box sets at present, as mentioned in the introduction to this column: 1) the niche return of vinyl and vinyl box sets, whose devotees affirm the importance of packaging as well as audio quality as a reason for their preference; and 2) the digital distribution of recordings, either by downloads or digital streaming.10 The CD box set seems endangered from both vinyl aficionados and from digital downloaders, in different ways.11 It may also be that the collecting impulses that have so shaped recorded sound culture come down to generational tastes. If CD and DVD technologies are both nearing the end of their technological relevance, then it will be DVDs that will be better equipped to transition to streaming and downloads, since the DVD’s format life has been relatively short.12 But to think that the power of the object (audio or otherwise) in collector culture will disappear in any quick or simple way is to misunderstand that culture, despite its love-hate relationship with the audio stockpile. In their scholarly focus and aesthetic lavishness, these box sets affirm for fans the transformative importance of music and a desire to understand and experience in various ways. And the work continues. For the past few years, Dust-to-Digital and Revenant have been collaborating on a new retrospective box set chronicling guitarist and Revenant co-founder John Fahey, which some sources suggest could be released as early as this month.

Image Credits:

1. Screamin’ and Hollerin:'” Deluxe Packaging

2. Goodbye Babylon Box Set

3. Susan Archie of World of Anarchie

4. By Brakhage, Volume 1-2: The Criterion Collection’s emphasis on DVD packaging

Please feel free to comment.

- See my interview with Revenant Records’ co-founder Dean Blackwood, “American Primitive: Revenant Records’ Tenth Anniversary,” in Perfect Sound Forever, April 2006. http://www.furious.com/perfect/revenantrecords.html [↩]

- Archie’s company has won numerous Grammy Awards for their work. They are involved in creating vinyl box sets as well. For Clem Coleman’s fascinating discussion with Archie, read the January 2003 interview in Sound Collector #8 here: http://www.worldofanarchie.com/pressf/sc8.html [↩]

- Of course, collectors have always been interested in film and television. But the historical focus for film and television collectors has been on paraphernalia rather than primary texts. [↩]

- Chuck Tryon, Reinventing Cinema: Movies in the Age of Convergence. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2009, 21. [↩]

- Derek Kompare, “Publishing Flow: DVD Box Sets and the Reconceptualization of Television,” Television & New Media. Vol. 7, No. 4, November 2006, 353, and Bernard Miège, The Capitalization of Cultural Production. New York: International General, 1989, 12. [↩]

- Sound recording as a medium remains based in the material. See Jonathan Sterne’s “The MP3 as Cultural Artifact,” New Media and Society, October 2006, Vol. 8, No. 5, 825-842. [↩]

- There are notable exceptions (e.g., The X Files box set, which as Kompare notes attempts to add value by having the object directly reference the show’s narrative, or the Seinfeld set, which does the same by referencing the show’s in-jokes). [↩]

- See Kevin Moist’s “Collecting, Collage, and Alchemy: The Harry Smith Anthology of American Folk Music as Art and Cultural Intervention,” American Studies Volume 48, Number 4, Winter 2007,111-127. [↩]

- Shuker notes that Revenant issued a fourth volume in 2000 that was part of Smith’s original intention. [↩]

- See Shuker’s “Formats, Collectors and the Music Industry” in Wax Trash and Vinyl Treasures: Record Collecting as a Social Practice, 57-82. [↩]

- Ibid. Shuker’s ethnographic research suggests a real generational shift in a preference for downloading audio as primary distribution point. [↩]

- The video game market is also working out its own relationship to the collectible object, while offering a range of options from download-only games to limited-edition packages. [↩]

I feel as if the box-set market and the digital streaming market are two completely different sides of the music spectrum that share an odd relation. Those artists who have intricate box sets crafted in honor of them have a certain significance in their music; that it has been well collected and thoroughly appreciated by some, and deemed significant enough to chronicle in its fullest aesthetic and aural quality. The digital streaming and downloading of music holds a certain browsing and exploring aspect for the listener that allows them to expand their tastes and preferences, while the box sets are for the most cherished of the listener’s collection, and are inevitably a niche market as any given person will have different tastes and preferences than the next. A direction that digital downloading of music might lead such a relationship is a reduction of the current music industry in its state of physical mass CD production, but a flourishing of creative offshoots in the form of such passionate fans who would take the time to create an elaborate and meaningful collection, but this is just speculation. Whatever form it takes and as long as there exists a music industry, there will always be an authentic, creative, and unorthodox collection of an artist’s work, and the CD box sets can be seen as a currently significant form of this. Holding a physical manifestation of an authentic part of cherished music history won’t easily top free digital downloading.

will*

I feel like what really make a person to be a music fan, or at least, we see him as a music fan, is showing his music collection, I still agree and believe that own a film or music within a actual box set is more powerful and meaningful than just download, although, today, we can easily down music and from from legal software, such as iTunes, box set selling market is still a dominated form in entertainment industry. What is the difference between spend 99 cents downloading a music from iTune and spend 15 dollars buying a actual album for a real music fan? I still believe that owning actual collections of music or movies are actually owning culture.

Pingback: Interview Blog