Black Swan, Cinematic Excess and the Full Body Experience

Amanda Klein / East Carolina University

Although art cinema and body genres, like horror and melodrama, offer very different film going experiences, Black Swan, which has been described as both “high-art trash” and as a low brow art film, effectively straddles these two modes of filmmaking. The film employs the conventions of art cinema in order to engage the mind, and the conventions of horror, melodrama, and pornography to engage the body. By doing so, the viewer’s experience of the film mirrors the journey taken by Nina (Natalie Portman), the ballet dancer who must embody the restrained, technically proficient white swan and the sensuous, out of control black swan. Darren Aronofsky depicts Nina’s slow and often terrifying metamorphosis into a sensual being as a continuous stream of sensorial assaults and the viewer, Nina’s extradiegetic doppelganger, is assaulted as well. Thus the film’s many moments of “excess” can be read through the lens of the art film—as marks of Aronofky’s authorial vision—and through the lens of the various body genres it samples—as images that implicate the viewer’s body in involuntary mimicry of the on-screen sensations.

According to David Bordwell,1 art films define themselves against the classical Hollywood paradigm of linear cause and effect narratives, strong, logical character motivations, and conclusive endings. Because art cinema privileges the director as author, “deviations” from mainstream filmmaking practices—such as an unusual camera angle or a visible cut—invite the viewer to seek either a realistic explanation (the camera angle represents the character’s perspective) or authorial motivation (the camera angle is the director’s signature). In other words, “Whatever is excessive in one category must belong to another” (654). According to this rubric, Black Swan is an “art film.” Its director, Darren Aronofsky, can certainly be considered a modern day auteur. He serves as writer, director, and producer for most of his films, ensuring that his unifying vision permeates his body of work; films like Pi (1998), Requiem for a Dream (2000) and The Wrestler (2008), all revisit the same interlinked themes of obsession, addiction, and the limits of the human body. However, what most associates Black Swan with the tradition of art cinema is the way that it appeals to the viewer’s mind. Its moments of excess—when Nina discovers that she is sprouting black swan feathers or believes that she hears voices when she is alone—invite serious viewer engagement and interpretation. The viewer must constantly question which images are real and which images are the products of Nina’s growing psychosis.

Although these scenes of excess engage the mind, they also directly address the viewer’s body. Linda Williams2 has labeled certain film genres—particularly horror, pornography, and melodrama—as “body genres” because they violate the classical realist paradigm of “efficient, action-centered, goal-oriented linear narratives” and offer gratuitous scenes of uncontrollable sensation, such as terror, arousal, and despair (603). Spectators are implicated in these spectacles of “ecstatic excess” and invited to experience these sensations in their own bodies. Black Swan contains several moments of ecstatic excess. For example, early in the film Nina is the guest of honor at a black tie fundraiser for her ballet company. When she retires to the bathroom she discovers a tear in her cuticle. She tugs at the skin and discovers, to her horror, that she has torn off a long strip of skin. Here a minor, everyday wound becomes uncontainable, potentially sabotaging the image of perfection that Nina must project at the fundraiser. She frantically washes her hands, but her blood continues to flow, threatening to stain her delicate white dress. Then, as suddenly as it arrived, Nina’s psychosis passes.

This scene of bodily injury is relatively minor compared to the atrocities presented in most horror films. However, its power lies in the fact that it is a commonplace injury gone terribly awry. James Kendrick’s review of Black Swan cites Anne Billson’s concept of “insidious little globs” to explain the efficacy of these scenes. These “small moments of film violence” resonate with viewers because they evoke our body memory of these experiences. Nina’s pain is all the more tangible because it is rooted in pain we have all encountered. Indeed, during the cuticle scene I found I was gripping my own hands together in an unconscious mimicry of Nina’s pain.

Another way to connect with the spectator’s body is to arouse it. In several scenes Nina sees (or imagines that she sees) people engaging in exhibitionistic sexual behavior: strangers on the subway make lewd noises, Thomas gropes her during rehearsal, and Nina watches as Lily and Thomas have sex on a table. We also see Nina’s face in close up as she experiences an extended orgasm. Although this orgasm is the product of Nina’s imagination, her visible, uncontrollable pleasure invites the viewer to experience sexual arousal or to turn away from it in embarrassment.

Nina and Lily (Mila Kunis) generate arousal

In addition to terror and arousal, Black Swan also generates tears. The film employs many of the conventions of the melodrama, a mode of filmmaking that invites the viewer to empathize with the plight of its suffering, powerless victims. The film employs wild shifts in tone in order to maximize emotional impact. For example, when Nina phones her mother from a bathroom stall to tell her that she has finally been selected to dance the lead role, the moment is intimate and exhilarating. We can see and hear Nina’s joy as she tells her mother, in the voice of a little girl: “He picked me, Mommy!” However, this moment of pure joy is immediately undercut when Nina emerges from the bathroom stall to see that the word “WHORE” has been scrawled on the mirror in red lipstick. The presence of the word reframes Nina’s achievement as a sleazy exchange with her director Thomas (Vincent Cassell). This scene is indicative of the dramatic reversals that punctuate the melodrama and “bring home the discontinuities in the structures of emotional experience” (Elsaesser3 387).

Black Swan also offers the viewer an intense auditory experience. Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake sounds in numerous auditory channels: in the tinkling of a music box, the low-def timbre of a cell phone ring, and in the clear tones of the violin that often accompanies Nina’s rehearsals. The viewer is thus placed in Nina’s obsessed perspective—like her, we hear Swan Lake everywhere we go. Furthermore, Aronofsky amplifies the sound of rehearsals, so that an art form most of us observe from a distance as light, airy and effortless, becomes earthbound and heavy. We hear Nina breathing in deep, measured gasps as she practices her routine over and over; we hear the sound of her sore, swollen feet pounding the ground over and over again; and we hear her retch and vomit in a dingy bathroom stall. These moments work in concert with a soundscape dedicated to keeping the viewer’s ears on high alert.4

When I watch a movie, I usually experience a split between mind and body. Generally (but not always) the films that force me to work to unpack their meanings are not the same films that make me laugh out loud or cry real tears. However, Black Swan offers, for lack of a better term, a full body experience of the cinema. Like Nina, the viewer is invited to inhabit both sides of the swan queen—white and black, mind and body. At the film’s conclusion, when Nina has embraced the black swan as part of her self, the viewer has taken a similar journey. While some viewers see Black Swan’s duel address and mixing of modes as a sign of Aronofksy’s confusion or failure, I welcomed the opportunity to become fully immersed in the filmgoing experience. I didn’t look at my watch, check my e-mail, or even shift in my seat. With mind and body fully engaged, all I could do was hold on tight and experience the ride.

Image Credits:

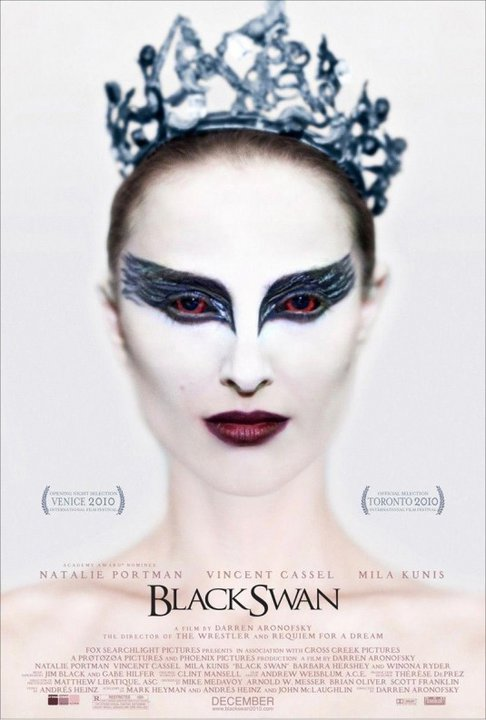

1. Movie Poster

2. Image 1. Nina’s wound is both everyday and out of control

3. Image 2: Nina and Lily (Mila Kunis) generate arousal

4. Image 3: At the end of Black Swan, Nina has embraced Odile.

Please feel free to comment.

- Bordwell, David. “The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice.” Film Theory and Criticism, 7th Ed. Eds. Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009. 602-616 [↩]

- Williams, Linda. “Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, Excess.” Film Theory and Criticism, 7th Ed. Eds. Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009. 649-657 [↩]

- Elsaesser, Thomas. “Tales of Sound and Fury: Observations on the Family Melodrama.” Film Genre Reader III. Ed. Barry Keith Grant. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2003. 366– 395. [↩]

- Bradshaw, Peter. “Black Swan Review”. The Guardian 20 Jan 2011. 4 Feb 2011. http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2011/jan/20/black-swan-review [↩]

What a super-smart, well-contextualized reading of this terrific film. I felt the same way when watching this film — totally engaged — and I agree that the mixing of genres is not confusion but brilliance. Thanks so much for this; loved it!

Hi Kristina

I tried to respond yesterday but I think something wonky happened with the site. Anyway, thanks for reading!

Since seeing this movie two months ago I have been talking about it and trying to figure out why it sat on my chest like a bad cold (but in a good way): because it evokes all three of the feelings Williams talks about her famous article and those Amanda Klein seamlessly connects to this movie. Going back to Requiem and Pi (but without re-watching either) I cannot help but think these same bodily sensations were felt when watching them as well. Great article!

I agree with the above viewpoints. Evocative and thought provoking movie and not quite cinematic trash at all!

Terms like “high/low art” are egocentric words that art critics sound egocentric. Graffiti was considered “low-art” until it became the preferred medium of the post-modern and the post-post-modern art world. Marcel Duchamp’s “Toilet” was also considered “low-art” until it was given an award. To label anything as high and low art is an example of the haughty attitudes critics hold against artists.

Critics become critics because they can’t make movies, or art; instead, they criticize artists in the worst way possible. I can appreciate a lot of critics. But when I’m in a critical studies class reading critical studies papers from critical studies people using these ridiculous phrases like “efficacy of a strategy of segmentation” when describing a hulu commercial, it makes me nauseous. Learn to humble your language to a 13th grade reading level and maybe someone will listen.

Pingback: Oscar Grouching ’10: Inception and Black Swan « Pussy Goes Grrr

I agree a lot with what’s been said above. “High and low art” are condescending terms that aren’t used very often. Although I’m not sure if those terms have been antiquated, they hold contemptuous baggage. Films openly manipulate the audience, and if the viewer feels disgusted or seduced it’s a success for the director. From writing, to editing, to marketing, Hollywood targets an audience for their film. Unlike “Inglorious Basterds” whose marketing campaign was completely erroneous, “Black Swan” delivered what it offered. With a director like Darren Aronofsky, there shouldn’t be any surprises. On the other hand, if the audience feels disdain the for the films attempt to influence their emotions than they have a certain legitimacy for their argument. High and low art is not the proper dialect.

This films critical and commercial success means that the popular public and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences embrace the movies as one of the best of 2011.

Like so many who saw Black Swan in theaters, I left the film deeply moved by what had assaulted me in the dark. This was to be expected. More astonishing was the sensational manner through which that end was achieved. The marketing campaign (leading up to the film’s initial release and running through award season) hammered home the searing depths of Natalie Portman’s performance and the force of Aronofsky’s directorial vision. Pretty typical rhetoric for a (wannabe) art-house underdog bidding for audiences and accolades. What startled me was exactly the recombinant genre-melding described in this article, the body-genres that jumped off the screen into the skin of the viewer.

I came expecting a visceral psychodrama, what has become typical of the radically subjective descent-into-madness fare. I believe Netflix calls it ‘mind-bending’. The shock to my system didn’t come from Portman or Aronofsky, both of whom did their jobs well (enough). Again, I come back to the marketing hype – that keen manager of expectations – which, far from ruining my viewing experience, managed to enhance it. This came in a distinct moment of realization when the nature of the body-genre reared an unanticipated head (in a hospital room with a pair of scissors)… When a delicious thought occurred: ‘They told me it would be arty, I had no idea I was signing on for horror.’ To me, that was much more interesting to me than whether Nina was losing her mind, Portman deserved an Oscar, or the director should be considered an auteur.

Hi Amanda

I have enjoyed reading your compellingly articulated thoughts on Black Swan. My own reaction to the the film is quite different and reading your article has encouraged me to write about it here.

I disagree to some extent with the discussion above regarding high/low terms (although I never really use “high art” or “low art”). Terms like “high brow” and “low brow” are subjective and fluctuate with changing attitudes and trends. However, they can certainly be useful in describing a work and where it fits in with other art forms. Upon first viewing Black Swan, my mother asked me to describe it to her. The first thing I could think of was that it was brilliant and experimental and artistic … but also kinda trashy. And there is nothing wrong with using those terms to describe the film because that is exactly what it is and what Aronofsky was aiming for. Words like “trashy,” “artsy,” “highbrow” and “lowbrow” are used as a means of differentiating that can be useful because they are so subjective and therefore express an individual’s opinion (and taste) instead of anything concrete.

I completely agree with Klein’s point that commonplace injuries are more cringe-worthy than excessive gore. I too grabbed my hands during that scene. Even more disturbing for me was the scene where Winona Ryder is stabbing herself. That scene was so effective in evoking a physical response from me because of the speed of the stabbing and Ryder’s facial expressions. It was unusual in a way I can’t pin down. I guess the best way to describe it was that Aronofsky was able to portray an individual who appeared absolutely disturbed and insane. I completely agree with Jess that I had no clue I was singing on to horror when I saw the film. The fact that I was unprepared made the impact of those scenes even stronger. I remember feeling physically exhausted when I left the theater.