Haunting Crime: the Gothic, the Grotesque and the Paranormal

Yvonne Tasker / University of East Anglia

“There is a paranormal turn in popular culture,” writes Annette Hill, a turn which for her encompasses both popular beliefs and popular cultural texts.1 Perhaps it goes without saying, but crime television has a longstanding relationship to both the Gothic and the paranormal—after all murder, death and ideas of evil are central to the genre. For decades both sociological perspectives and procedural conventions have framed crime television in terms of realism, emphasising the ways in which the genre involves contemporary concerns of surveillance or deals with societal perceptions of crime, deviance and danger in a risk society. A preoccupation with realism certainly makes sense for thinking about much crime television, with its delineation of evidence and motive, its exposure of brutal social forces set against the more mundane everyday qualities discerned through the interaction of professionals under pressure. The genre’s evocation of modern urban life with its marked class divisions and racial inequalities certainly speaks to social realities, making these crucial questions for an analysis of crime television. Yet preoccupations with realism have a tendency to occlude discussions of style, as if realism were unmarked by conventions even when we know—as critics and students—that this is not so. In what Derek Kompare’s analysis might deem a particular sort of CSI-effect, style has forcefully re-emerged in scholarly work on crime over the last decade.2 In this context it may also be worth thinking about connections between crime and the highly stylised traditions of the Gothic.

Where such connections are discussed, there is a tendency to loop back to literature and to the rich Gothic heritage of crime fiction. Television crime may have a shorter history, but it too has a striking repertoire of Gothic texts on which to draw. Two rather different, yet equally quirky (and at times distinctly arty) hybrid shows of the 1990s stand out as foregrounding crime’s Gothic intertexts: Twin Peaks [1990-91] and The X-Files [1993-2002]. These shows have been extensively discussed for their distinctive evocation of elements drawn from crime, horror, noir, melodrama as well as soap and science-fiction. However culturally visible and even influential these shows have proven to be, they are also both marked by the seeming difficulty of drawing them into accounts of crime television as a genre. My guess is that this has to do with the long time association of crime television with the police drama series and its characteristic realist aesthetic (so that the 1990s is the decade of Law and Order [1990-2010], Homicide [1993-99] and NYPD: Blue [1993-2005]). Through the 2000s however, crime television has not only proliferated but is also far less wedded to the urban squad room. With shows focused on special units, private investigators and scientific advisors, crime television is plainly a space that exceeds any one genre even while it remains absolutely generic. Gothic tropes provide one of several ways into the historical development different contemporary crime genres.

Helen Wheatley writes that “Gothic television is visually dark, with a mise-en-scene dominated by drab and dismal colours, shadows and closed-in spaces.”3 Gothic tropes feature in crime television in two distinct ways. Firstly, there is the presence of explicitly supernatural or paranormal elements within crime or investigative shows. Obvious examples would be vampire crime television (the crime fighters of Angel [1999-2004], Blood Ties [2007], Forever Knight [1992-96] or Moonlight [2007-8]) and psychic crime or mystery shows such as Ghost Whisperer [2005-10] or Medium [2005-] in which visions and/or communication with the dead initiate and are central to the development of the investigative plot. (Evidentially there is an intriguing, if rather predictable, gendered dimension to these examples with male vampire crime fighters figuring the supernatural in somewhat different terms to female psychics.)4 On the other hand there is crime television’s widespread use of macabre, Gothic imagery—particularly the low key lighting and expressionist aesthetic associated with gothic film—a phenomenon that has attracted attention through the bodily fascinations foregrounded in forensic crime television (a mode that foregrounds the scientific not the paranormal). The grotesque and macabre is a presence even in crime shows which tend towards a very different aesthetic, with the figure of the serial killer – imagined as a sort of artist, staging darkly elaborate crime scenes – as one linchpin. (Criminal Minds [2005-], CSI [2000-] and Dexter [2006-] have all deployed Gothic tropes to visualise the serial killer and his/her crimes but so has a realist show such as Law and Order). Interestingly, crime shows premised on the supernatural do not necessarily deploy a Gothic aesthetic. For example, Warehouse 13 [2009-] which clearly trades off The X-Files while playing for comic effect in its characterisation of Secret Service agents ambivalent in their assignment to the policing of supernatural artifacts. We might also contrast the very different style of psychic shows Medium and Ghost Whisperer, the latter redolent with Gothic imagery while the former is more conventional in its styling.

In their discussion of Dexter, Simon Brown and Stacey Abbott suggest that Gothic is in many ways a culturally acceptable term for talking about horror. While there may well be an argument to be made about terminology and cultural value (witness the mobilisation of “noir” as a designator of quality in the context of potentially sensationalistic subject matter), the Gothic brings together a sense of darkness and dread with the evocation of social disruption which stretches from the uncanny to the overtly paranormal. It is here we might productively situate a crime show like Cold Case [2003-10] in relation to the Gothic. Cold Case showcases cop Lily Rush’s heightened intuitive sense which allows a sort of resurrection of the dead, amidst a stirring up and re-staging of past events. In this, Cold Case couples a generic staple of crime television—the investigator, often though not always female, who is haunted by the past—to the uncanny juxtaposition of past and present and the uncovering of secrets so characteristic of the Gothic. The connections between American crime television and the Gothic reside as much in the uncanny ability of the investigator to uncover such secrets, as in explicitly grotesque imagery. This uncanny intuition is the insistent premise not only of Cold Case’s Rush but also of Detective Goren in Law & Order: Criminal Intent [2001-]. As Wheatley argues, the Gothic turns on the domestic; if crime television is more often thought of as dealing with the public world—as its defining preoccupation with themes of law and justice would suggest—the genre’s use of Gothic tropes allows a blurring of the official and the intimate concerns of the domestic. It is through such strategies that crime television suggests and exploits the haunting presence of personal pain in the disciplinary structures of public morality.

Image Credits:

1. The X-Files, screen capture provided by author

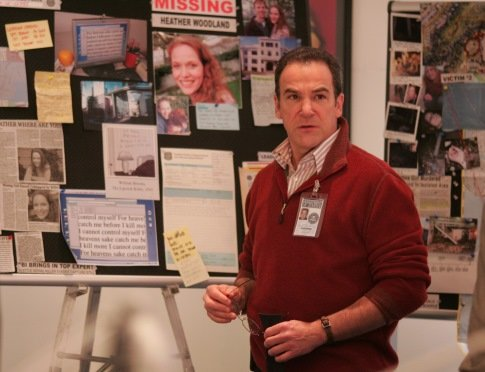

2. Criminal Minds, screen capture provided by author

3. The Ghost Whisperer

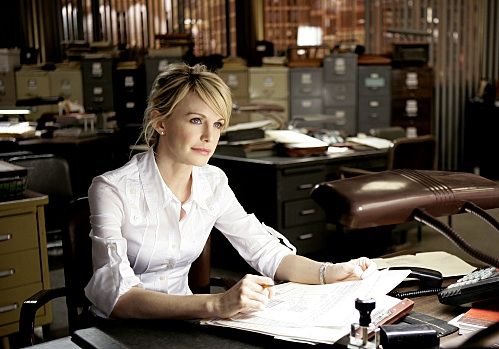

4. Cold Case

Please feel free to comment.

- Annette Hill, Paranormal Media: Audiences, Spirits and Magic in Popular Culture, Routledge, New York, 2011, p.1. [↩]

- Kompare astutely argues that the “’CSI-effect’ is itself a media production” and that it is over all within television that the show has had most obvious effects. Derek Kompare, CSI, Wiley-Blackwell, 2010, p.81. [↩]

- Helen Wheatley, Gothic Television, Manchester University Press, p.3. [↩]

- Diane Negra has remarked on the inscription of male vampires as “safe erotic objects” who are represented within popular culture as “less likely to commit crimes than to solve them.” “Television’s Vampire Detectives,” paper presented to Society of Cinema and Media Studies Conference, Los Angeles 2010. [↩]

Brown and Abbott’s comment about horror reminds me that the term “horror” has its literary roots in the early Gothic novel, describing the reaction to discovering something fear inducing or stomach churning. Also, I’m glad you discuss the domestic since Gothic work is so connected to the personal and psychological, often revealing the perverse and morbid in every character. Thank you for the thought-provoking article.

Pingback: Flow: Gothic