The Fringe Benefits of Symbolic Annihilation

Esteban Del Río / University of San Diego

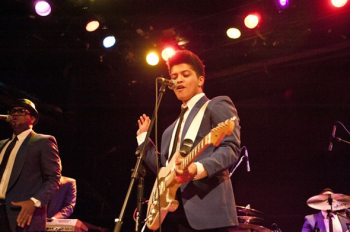

Last semester1 I spoke with an undergraduate student, now pursuing graduate study in journalism at Columbia University, about his Filipino heritage and the near absence of Filipino representation on television in the United States. Despite a deeply rooted historic presence in this country and high levels of participation in mainline U.S. institutions like the military, Filipinos barely exist on U.S. television. Recent screen history features a handful of familiar Filipino faces whose biracial positionality allows for flexible casting; actors like Lou Diamond Phillips, Phoebe Cates, and Vanessa Hudgens have portrayed popular charcters, although not necessarily coded as Filipino. Singer Bruno Mars, who currently enjoys pop stardom, commented to the New York Times on skepticism he garnered from record labels early in his career: “I guess if I’m a product, either you’re chocolate, you’re vanilla or your butterscotch. You can’t be all three.”2

My student and I talked about how the lack of Filipinos in general market media exemplified a key idea of Gerbner’s3 notion of symbolic annihilation: if a group has no representation on television, they will not exist in the public consciousness and issues important to that community are never mentioned within frameworks of public deliberation. Tuchman and others added to the idea in the 1970s, and it became very useful in understanding the relationship between the symbolic and the real, especially in the cases of ethnic minorities, women, and queer representation. For the discussion with my student, the core idea behind symbolic annihilation meant that because Filipinos are absent in news discourses and as characters on scripted programs: no positive role models exist for Filipino youth; issues pertaining to the Filipino community are not made available for consideration by the larger public; and Filipinos are not rendered as part of the national imaginary.

The notion of symbolic annihilation lent fuel to advocacy efforts for more just, equitable, and positive depictions of marginalized groups within an emergent politics of representation. By the 1980’s The Cosby Show, devoid of the potentially stereotypical and perhaps more realistic working-class depictions in programs like Good Times and Sanford and Son, put black folks’ best feet forward with stories of a wealthy family that stood defiantly against an demoralizing and deadly existing regime of representation about blackness. But The Cosby Show also provoked a compelling line of argument against this strategy, detailed through audience research in Jhally & Lewis’ Enlightened Racism4. Simply replacing negative stereotypes with positive ones supported ideologies of the American Dream and placed blame on the majority of African Americans who had not achieved the level of economic success displayed by the Cosbys.

Positive representations of Latinos yield something more complicated. Despite a presence here before the U.S. even existed, Latinos are invented and reinvented in general market media, usually following economic cycles. When times are bad, as they are now, Latinos are lumped into moral panics about illegal immigration and invasion from Latin America. When times are good, as they were in the late 1990s and early 2000s, Latinos are celebrated as a new, profitable market segment and potential constituency for politicians. Because of the nature of the southern border and continuous migration over centuries, television discourses about Latinos link rather easily with “newcomer” narratives of the American Dream. But as television re-invents Latinos, even in positive ways, it is also clear that overwhelming, demographic-driven market forces articulate a Latino structure of feeling that fits within existing commercial logics. For many, the celebration of a brown chic over the last ten years brings welcome relief from a history of being either a cartoonish character or non-existent. However, broadly, the articulation of Latinidad on general-market television sanitizes, essentializes and tames any threat to dominant U.S. ideologies and institutions that the Latino experience may challenge. It creates a people, and then proceeds to lead them to products and services that any docile, different American would desire. Therefore, the important question for scholars has to do with the purposes and conditions under which positive representations take place. Instead of positive representations being the end result of television criticism, they should be a point of departure. More complex and interesting characters and storylines show up in The George Lopez Show, Ugly Betty, Modern Family, and Desperate Housewives, but glancing across the television spectrum, in news, advertisements, and programs, we see more or less the same version of the friendly (if not sexy) Latino. But at least we’re on TV.

Symbolic annihilation and other concepts like it have moved from the academic to the pragmatic, and helped cultivate a more diverse television landscape. There is a growing presence of marginalized groups on television and more flattering portrayals. Filipinos are not quite there, but surely they will be. But one thing needs to be said about not existing on television: you, your identity, and your community will not be manipulated as easily. In other words, there may be benefits to being placed on the fringe of mainstream consciousness through symbolic annihilation in terms of the absence and erasure of a group. For groups that live below television’s radar, there is a freedom to articulate the group from below, from a more vernacular location, using multiple voices. Of course, existing regimes of representation often need to be contested, and the search for role models is important, especially for those isolated from others who inhabit their subject position. But the idea of being “left alone” by the manipulative, commercial-driven mainstream cultural apparatus does have its charms.

Not too long ago, Chicano activists who were tired of the long struggle to correct stereotypical images in general market television began to cultivate a different strategy: make your own media from a Chicano perspective. In Shot in America, Chon Norega documents this process.5 Today, like the Chicano activists of the 1970s who cultivated “independent” media practice, we don’t need to turn solely to mainstream television, film, or news discourses for models of identity and community. DIY media provides increasing potential and power to render authentic notions of both unity and difference. Perhaps even those of us who have parts of our identities costumed, made-up, and thrown upon the national stage can gather back some of our dignity and purpose by glancing away from the bright lights.

Image Credits:

1. Bruno Mars

2. The Cosby Show

3. George Lopez

Please feel free to comment.

- This essay originated as a position paper at the Flow 2010 Conference, on panels titled “The Pitfalls of Positive Representation.” Thanks to the panelists and audience for ideas that have made their way into this piece. [↩]

- http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/06/arts/music/06mars.html?_r=1&scp=1&sq=filipino%20rapper&st=cse [↩]

- Gerbner, G. (1972). Violence in television drama: Trends and symbolic functions. In G.A. Comstock & E. Rubinstien (eds.). Television and social behavior, vol. 1: Content and control. Washington, DC: Us Government Priting Office, pp. 28-187 [↩]

- Jhally, S. & Lewis, J. (1992). Enlightened racism: The Cosby Show, audiences, and the myth of the American dream. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. [↩]

- Noriega, C. (2000). Shot in America: Television, the state, and the rise of Chicano cinema. Minneapolis: Minnesota. Thanks to Mary Beltran for helping me make this connection. [↩]

I am curious about the role of pan-ethnic Asian identity constructions in the perception of Filipinos. While they absolutely have a unique postionality due to their colonial history, I feel that they often get lumped into a giant all-encompassing Asian category. I wonder if the lack of “Filipino” representations is related to that unique positionality and the difficulty of constructing that postionality in TV narrative to a U.S. audience that is usually ignorant to Filipino colonial history and has little conception of a heterogeneous Asian population within the U.S.?

I think there certainly is a lot of ignorance about Filipino colonial history – and the historical presence of Filipinos in the U.S. Your point about the use of pan-ethnic categories is interesting. In my work on Latina/o culture, the overdetermined nature of pan-ethnic categorization makes it ripe for innovative communication inquiry: it speaks to the fact and fiction of difference as its articulated in our present conjuncture.

When I first presented this at the FLOW conference, I was attempting to be provocative, but after those discussions, I’ve come to think that the “fringe benefits” of cultural erasure may be a useful strategy in the politics of representation.

Pingback: Series Blog