Show Musical Good, Paired Segments Better: Glee’s Unevenness Explained

Kelli Marshall / University of Toledo

Before I explain why Fox’s musical comedy-drama Glee often feels uneven, I’d like to point out what the show gets right. Principally, Glee‘s creator, Ryan Murphy (Nip/Tuck), has adopted the most suitable musical subgenre for his project: the show musical.1 Of the subgenres — fairy tale, folk, and show — the show musical, whose numbers typically perform a purpose (e.g., auditions, rehearsals, performances), best caters to Murphy’s objective that the cast doesn’t “suddenly burst into song.”2 When the characters sing, Murphy claims, they will do so only when they are on stage practicing or performing, in the rehearsal classroom, or in a fantasy state (i.e., a performance in their head). Limiting the numbers to these situations, he believes, will make Glee “more accessible to people.”3

Glee may have assumed the best musical subgenre for its purpose, but the show doesn’t always thrive within said subgenre. And people notice. For example, reviews of the first season swing frantically back and forth, from the show is “so funny, so bulging with vibrant characters” and “these performances are wonderful, […] shaping a fully realized world” to this is “wildly incoherent” and “simply a mess.” Much of this unevenness, I believe, boils down to Murphy’s refusal to implement consistently one of the most important structural conventions of the musical genre: paired segments, evenly spaced thematic and/or sexual comparisons/oppositions underscored via setting, shot selection, music, dance, and personal style.4 As Rick Altman explains, with musicals the viewer must “forget familiar notions of plot, psychological motivation, and causal relationships” and surrender instead to “simultaneity and similarity” (e.g., male/female, talented/inept, teacher/student, gay/straight, popular/ostracized).5

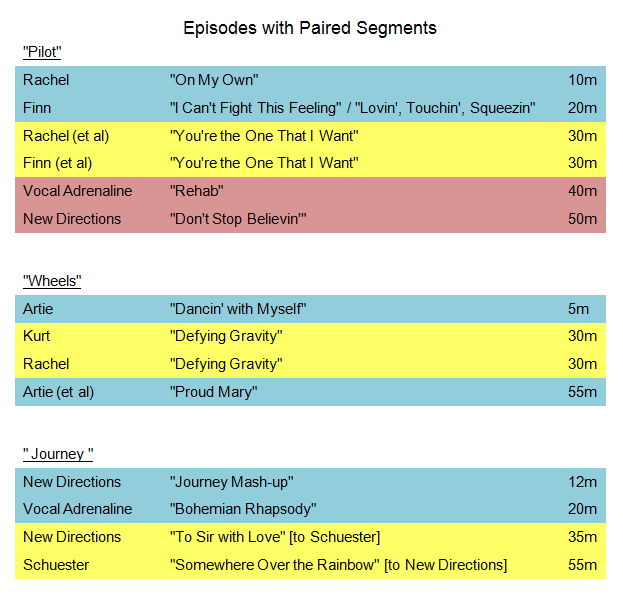

At least three episodes of Glee feature uniform parallel segments: “Pilot,” “Wheels,” and “Journey.” Significantly, these episodes are also the most highly praised of the season.6 Unlike those which critics have panned or are divided over (e.g., “Hairography,” “Once Upon A Mattress,” “Home,” “Funk“), these three carefully and consistently juxtapose individual characters and groups. For example, “Wheels” begins and ends with Artie (Kevin McHale) dancing in the school’s auditorium, first by himself and then with his friends in the glee club. Likewise, “Journey” contrasts the vocal and dance abilities of New Directions with that of its show-choir nemesis, Vocal Adrenaline, and then closes with another parallel segment: New Directions singing to their teacher/mentor, Mr. Schuester (Matthew Morrison) and Schuester returning the favor to his students (see table above). Through these parallel numbers, the characters develop and the viewer understands their growth.7

What’s more, the musical numbers in these three episodes are limited (unlike those in “The Power of Madonna,” for instance) and spread evenly throughout. For example, like its show-musical predecessors Singin’ in the Rain (Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly, 1952) and The Band Wagon (Vincente Minnelli, 1953), Glee‘s “Pilot” features a song about every 10 minutes; moreover, “Wheels” positions its songs in a nearly perfect arc: one at the beginning, middle, and end. Finally, each of the numbers in these episodes serves a convincing purpose. For instance, in “Pilot,” Rachel (Lea Michele) auditions for glee club with “On My Own,” effectively informing the viewer she is both passionate about Broadway musicals and isolated in high school. Echoing this number, Finn (Cory Monteith) sings REO Speedwagon’s “I Can’t Fight This Feeling,” conveying to us that although glee club isn’t traditionally for football players, he won’t be able to “fight the feeling” to join.

More colors, more erratic.

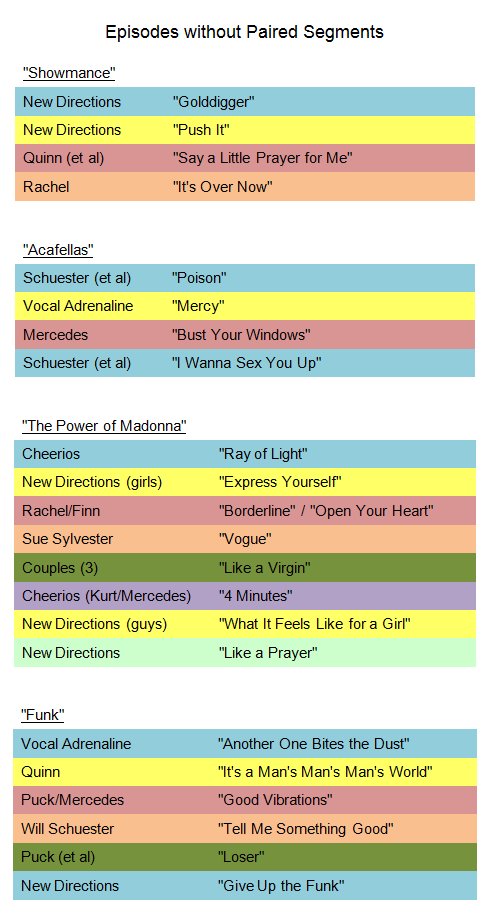

While “Pilot,” “Wheels,” and “Journey” achieve narrative and stylistic continuity via paired segments and purposeful performances, a large number of Glee‘s episodes do not. As a result, the entire series can feel unbalanced, schizophrenic even. For example, the majority of the musical numbers in “Showmance,” “Acafellas,” “The Power of Madonna,” and “Funk” may individually charm and/or entertain the viewer, but because they are detached from one another, they fail to form a coherent whole (see table above). Admittedly, Sue Sylvester’s (Jane Lynch) copycat performance of Madonna’s “Vogue” is interesting and ambitious, but it has no corresponding number; hence, we do not fully understand what purpose it serves. The same goes for Schuester’s weird flirtation with Sue (“Tell Me Something Good”), Rachel’s cries over her love for Finn (“Take a Bow”), and Mercedes’s (Amber Riley) fiery reaction to Kurt’s (Chris Colfer) rejection of her (“Bust Your Windows”). Had Ryan Murphy et al created musical numbers through which Sue, Finn, and Kurt could reciprocate their feelings, rather than using snippets of dialogue or in some cases silence, these episodes would likely feel more complete. In this genre, reacting to such emotional performances via dialogue alone generally doesn’t cut it.8

In interviews, Murphy claims that with Glee he is creating a “postmodern musical” in the vein of Chicago (Rob Marshall, 2002) or Moulin Rouge (Baz Luhrmann, 2001). But what he ostensibly fails to realize is that these two films — while perhaps modern in look, themes, and style (editing in particular) — still conform to the structure of classical musicals, operating almost exclusively through doubling or paired segments.9 Furthermore, Murphy admits that he bases Glee‘s musical numbers on “stuff that I like and that I think fits the characters and moves the story along.” On its surface this is perhaps fine, but since musical narratives — like all genres, television shows included — necessitate structure, that “stuff that Murphy likes” needs to be framed more consistently within matched scenes and sequences. Perhaps then Glee wouldn’t feel so uneven.

Image Credits:

1. Hey kids, let’s put on a show (musical)!

2. Image by author.

3. Artie initially “dancing by himself” and then “proudly” with New Directions.

4. Image by author.

Please feel free to comment.

- The show musical is also known as the backstage musical and the self-reflective musical. On the latter, see Jane Feuer, “The Self-reflective Musical and the Myth of Entertainment,” Genre: The Musical. Ed. Rick Altman (London: Routledge, 1981), 159-74. [↩]

- Well-known examples of the fairy tale musical are Top Hat (Mark Sandrich, 1935) and An American in Paris (Vincent Minnelli, 1951), of the folk musical, Oklahoma! (Fred Zinnemann, 1955) and Meet Me in St. Louis (Vincent Minnelli, 1944), and of the show musical, Singin in the Rain (Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly, 1952) and Cabaret (Bob Fosse, 1972). For a detailed explanation of the three musical subgenres, see Rick Altman, The American Film Musical (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987). [↩]

- There are other reasons the show musical is the best option for Glee and Murphy’s aims: first, it is the subgenre most closely tied to the music industry (Altman 271); second, its performances (like those in the folk musical) emphasize “the integration of the individual into a community or group” (Feuer 166); and third, it employs clichéd stereotypical characters but mainly to “restore meaning to the atmosphere that seems devoid of it” (Altman 252). [↩]

- Altman, 33-45. While I’m arguing that Glee feels uneven because it consistently rejects paired segments, I’m also aware that the show likely feels this way because it juxtaposes ridiculous storylines (e.g., Terri Schuester’s fake pregnancy, Sue Sylvester’s outlandish attempts to sabotage Schuester and the glee club) with rather poignant ones (e.g., Kurt’s conversations with his father, Quinn’s parents disowning her). Moreover, as Todd VanDerWerff points out, some of Glee‘s unpredictability may also have to do with its three-writer problem, i.e., Glee‘s three writers — Ryan Murphy, Brad Falchuk, and Ian Brennan — “seem to have wildly different ideas of what the show is.” [↩]

- Altman, 28. In his work, Altman mostly considers heterosexual romantic couples; however, musicals also create parallel segments for groups of characters like those found in Glee, for instance, Sharks/Jets in West Side Story (Robert Wise and Jerome Robbins, 1961), Pink Ladies/T-Birds in Grease! (Randal Kleiser, 1978), and children/parents in Mary Poppins (Robert Stevenson, 1964), The Sound of Music (Robert Wise, 1965), and Annie (John Huston, 1982). [↩]

- For critical reception, see The Onion‘s AV Club, Time‘s Tuned In, Metacritic, as well as Wikipedia‘s summaries of “Pilot,” “Wheels,” and “Journey.” I should note, however, that while “Wheels” was widely praised, it was not without controversy; some performers with disabilities claimed it was inappropriate to cast an able-bodied actor (Kevin McHale) as a disabled student. Still, this criticism, while perhaps warranted, has little to do with the show’s narrative structure. [↩]

- One of the other relatively highly praised episodes, “Dream On,” also includes paired segments. First, Schuester and his old show-choir nemesis, Bryan Ryan (Neil Patrick Harris), reunite by singing “Piano Man” and then compete with “Dream On.” Second, Rachel and her mother, Shelby (Idina Menzel), pair up for “I Dreamed a Dream” (this also recalls Rachel’s Les Miserables song from the “Pilot”). Third, an idealistic Artie performs “Safety Dance,” and then later, a more rational Artie leads New Directions in “Dream a Little Dream of Me.” [↩]

- Musical numbers in these “unpaired-segment” episodes are also unevenly timed. For example, “Showmance” features songs at 10m, 35m, 50m, and 55m; “Acafellas” at 17m, 22m, 40m, and 50m; and “The Power of Madonna” at 10m, 14m, 22m, 38m, 41m, 52m, 58m, and 62m. Moreover, unlike “On My Own,” “I Can’t Fight This Feeling,” and “To Sir with Love,” many songs in these episodes fail to serve a convincing purpose. For instance, Finn and Rachel’s “Borderline”/”Open Your Heart” duet takes the characters nowhere; at the end of the episode, neither character’s heart is truly opened to the other. Likewise, “Gold Digger” does little more than showcase Mr. Schuester’s rap/dance abilities. [↩]

- Marsha Kinder, “Moulin Rouge,” Film Quarterly (55.3): 52-59; Karen Perlman, “Cutting Rhythms in Chicago and Cabaret,” Cineaste, (Spring 2009): 28-32. [↩]

Great piece Kelli! I never thought about the show’s lack of “paired segments” but looking at your colorful charts, you are right–some of the least satisfying episodes are those with erratic song choices.

I too am often left feeling unsatisfied at the end of a GLEE episode (despite the fact that I really enjoy the musical numbers individually). Rather than using musical performances to move the narrative forward or create an emotional break through, songs seem to be chosen based on how well they will chart on I-Tunes the next day. This is a shame because the show could really be doing some great work in terms of upating the musical form for television.

Lots to think about here–thanks!

Kelli-

Very insightful piece! As you point out, there is plenty of recent Glee criticism and commentary, and I appreciate your ability to thoughtfully consider the generic elements present (or not present!) that help/hinder the show’s evenness. Your observation that the show musical is the most lucrative option for Murphy, but that it isn’t necessarily executed in the smartest way, is specific and convincing.

Thanks for this interesting piece, Kelly. I really appreciate your illustration and discussion of how Glee’s pilot, “Wheels,” and “Journey” are particularly balanced in relation to their storylines, character development, and tone as witnessed in the musical numbers, and I agree that as a result they can provide a particular sense of “completeness”” to many viewers. I wonder, however, at whether such episodes don’t also feel particularly predictable and nostalgic for earlier eras, when we were more likely to expect this kind of tonal balance in a film or television episode, musical or otherwise? While as a fan I certainly have enjoyed the “balanced” episodes mentioned in relation to that balance, I would not have stayed with the show if it didn’t often surprise as well and not meet previously established expectations at times in relation to the musical numbers and various storylines. Do you feel that Glee would be more successful if its episodes always aimed for the musical balance achieved, say, in “Wheels”?

Please excuse the typo on your name in my above comment, Kelli. :)

Thank you for such a thought-provoking article! It certainly made me think about Glee from a really different perspective that I hadn’t considered before. I wonder, though, if we should expect Glee to adhere to the structure of the traditional musical–Glee is not a musical, after all. I’d say it’s a transgeneric show that draws on the elements of teen drama, comedy, and the musical, but mixes them in unexpected ways. Considering the genre mixing happening in Glee, I find it unsurprising that the show has moved beyond the conventions of the traditional musical.

Thanks, Amanda and Sarah! After rewatching (and timing) several episodes/numbers, I too was surprised that the shows most of us (on Twitter, blogs, and the like) consider “erratic” do not include paired segments or any sort of pairing whatsoever. Perhaps next season will offer us a more conventional structure. Well, a girl can dream, right? =)

Hi, Mary — thanks for reading and commenting! Honestly, I do think Glee would be more successful critically if its episodes aimed more consistently for the musical balance in “Wheels” or “Pilot” or “Dream On.” Murphy et al could still surprise audiences week to week via spectacle, storyline, characterization, etc. just as his musical inspirations (Moulin Rouge and Chicago) surprised their audiences. However, without some sort of narrative structure, Glee just comes across as a total mess, does it not?

Hi, Melanie — thanks to you also for reading and commenting! You write, “Glee is not a musical but a transgeneric show.” You’re definitely right; it is a transgeneric show. But isn’t it one that is based almost exclusively on the (show) musical? The reason I keep returning to that notion is that’s how Murphy always describes it:

— “I was interested in doing a musical, but I wanted to do sort of a post-modern musical. That was always how I sold it.”

— “I kind of want to do a musical, but I don’t know what that would be. And [the network] said, well, we’ve been wanting to do a musical forever, and we can’t figure out how to crack it.”

Then again, as I argue above, Murphy doesn’t always want to implement the structure of the musical. So who knows? =)

Pingback: GLEE’s Unevenness Explained | Unmuzzled Thoughts (about Teaching and Pop Culture)