Avatar as Technological Tentpole

Charles R. Acland / Concordia University

The jokes describing Avatar (2009) have been almost as good as the movie: Pocahontas meets Halo, Dances with Wolves in Space, James Cameron’s Ferngully, and a recruiting vehicle for Blue Man Group. With the juggernaut roll-out of Cameron’s first fiction feature since the unsinkable Titanic (1997), such humorous spins are to be expected. But it is one thing to put the promotional engine in high gear and it is another to deliver a financially successful, audience-pleasing, and critically respected film to match the hype. By virtually every measure, Cameron has done exactly that with his body-swapping environmentalist space opera. Avatar enjoys an impressive cumulative score on the omnibus movie review website Rotten Tomatoes. And audience curiosity bulked up the film’s box office to $429 million domestic, and $1.33 billion worldwide, in less than four weeks, making it already the second highest grossing film of all time.

Avatar is a “tentpole” film, which means it is the centerpiece of distributor Twentieth Century Fox’s slate of recent releases. There is no stable definition for what counts, but tentpoles typically have large budgets, especially for promotion, and might be expected to launch or continue a film franchise. A major distributor may have a couple of tentpole films over the course of a year. Such films are often mentioned in the annual reports of media corporations, as distributors temporarily bank corporate fiscal health on the success of those particular releases. With tentpoles drawing the largest audiences, a distributor fills out its “tent” with films that might be directed toward genre or niche audiences. For exhibitors, a tentpole benefits simultaneously released films, as, say, parents drop off their kids to see Avatar and then take in It’s Complicated (2009) on the screen next door.

But Avatar is also something of a different order. Few media products have such elevated expectations as Avatar. And these expectations are not only for its own success, but for a number of other products and technologies it has bundled to share its revenue-generating glory. Remarkably, many believe that this film marks a revolutionary moment in the history of cinema, that it is a “game-changer.” Steven Soderbergh was one unlikely auteurist voice who sang the praises of Avatar before its release based on partial footage he had seen during the production process. He went so far as to describe it as a “benchmark” movie, comparable to The Godfather (1972) in its day.1 Similarly, DreamWorks Animation head Jeffery Katzenberg asserted, “I think the day after Jim Cameron’s movie comes out, it’s a new world.”2 At the film’s premiere, director Michael Mann declared, “There’s before this movie and after this movie.”3

The language of the “game-changing” impact of Avatar is illuminating. First, the film represents stupendous budget aggrandizement, and even more Byzantine accounting procedures than usual. The official budget from Fox and Cameron’s production company Lightstorm Entertainment was $230 million, up from the initial budget of “close to $200 million” when Fox’s participation was first announced in January 2007.4 So unrestrained was Cameron’s spending that that amount soon seemed like a bargain next to unofficial estimates. Once we add all international distribution and marketing expenses, and the personal financial commitment of individual investors, including Cameron, the figure is closer to $500 million.5 That Avatar‘s grosses rapidly surpassed its record-breaking budget gives major industry investors confidence in the financial viability of the top end of the budget food chain. But take note that a parallel 2009 Hollywood success story is that of Paranormal Activity (2009), a $15,000 movie that made over $100 million in domestic release. These two films thus lay out two contrasting contemporary blockbuster economies.

Trade pundits and cultural commentators most frequently discuss Avatar‘s game-changer status in relation to 3-D exhibition. In fact, there is an industrial agreement that 3-D is the next revolution in cinema history, with, as Time put it, Avatar a vanguard example of the future of the format.6 In a 60 Minutes feature on Cameron, Michael Lewis, head of the leading 3-D exhibition technology outfit RealD, said “Avatar is potentially the Citizen Kane of this medium.” 3-D exhibition, which has proven lucrative over the last few years, is being taken as a driving force for the acceleration of the conversion of theaters to digital exhibition, a conversion that affects both 3-D and 2-D films. In this respect, Avatar’s influence extends beyond 3-D, speeding up the obsolescence of celluloid projectors in mainstream theaters.7

The spark to 3-D exhibition is but one of several other processes either developed or exploited by Cameron at the production end, including the Simulacam, which provides filmmakers and crew an immediate visual approximation of 3-D and CGI enhancements of shots. Cameron has also made 3-D shooting more director-friendly by developing, with cinematographer Vincent Pace, the patented Pace/Cameron Fusion System, which is light weight and allows for easier changes to the point of convergence between the two digital cameras required for shooting the 3-D effect.8

The “game-changing” hyperbole is manifest in other aspects of the Avatar commodity world. Game developer Ubisoft released a 3-D Avatar game just weeks ahead of the film, a move that prompted Variety to wonder whether or not this product was yet another “game changer,” pun intended.9 Ubisoft has been seeking involvement in the feature film business, acquiring prestige CGI company Hybride, based in St. Sauveur, Quebec. A further complication to the lines dividing entertainment industries, Cameron contracted Hybride to do effects for Avatar, the movie. Panasonic is using Avatar in an international cross-promotion deal to sell its own new HD 3-D Home Theater system.10 This push links to the gaming industry as Ubisoft’s Avatar: The Game requires a 3-D enabled television or monitor in order for the full 3-D design of the game to work. But it also looks ahead to 3-D television programming. Accordingly, following Avatar‘s apparent box-office success, several television channels announced plans for 3-D broadcasting.

So, while extraordinarily conventional in story and characterization, Avatar is celebrated and promoted to stand out as a flagship work beckoning the next wave of industrial and consumer technologies and entertainments. With Avatar, we have 3-D filming processes, 3-D exhibition, digital exhibition, and 3-D home entertainment all counting on the film’s appeal for their own advancement. And given that corporate participants in the making of Avatar span from Quebec’s Hybride to New Zealand’s Weta Digital, the film is a good example of a transnational economic entity. Avatar is a technological tentpole under which we find not only other movies and appended commodities, but media formats and processes that slide into our lives as supposedly essential. Technological tentpoles introduce and promote hardware and media systems; such entities advance the very notion of a reconstructed cinematic apparatus as well as that of a wider audiovisual environment.

Consider Avatar‘s newspaper advertising, which promises the routine geographical reach of a wide-release blockbuster (“everywhere”), but also format choice (“everyway”) between 2-D, digital 3-D, and Imax 3-D presentations, each with distinct appeal and pricing. A few years ago, David Denby claimed that the expansion of exhibition possibilities for film has produced “platform agnosticism,” such that people no longer care how and under what conditions they see films, resulting in a coup de grâce for traditional cinephilia.11 Avatar‘s advertising shows just how erroneous Denby was. Instead, the multiplying formats have produced a heightened platform consciousness. In essence, the newspaper campaign sells film and formats at once.

The varieties of media materiality have ample representation in Cameron’s vision of the future. The film is replete with screens on screen: 3-D screens, topographical screens, video screens, computer screen, touch screens, hand-held digital tablets, and curved screens. Even the thematic center-point of the film–the conversion of our human characters into their respective avatars as giant blue extraterrestrial creatures, the Na’vi–appears as a form of transportation, with abstract blazing lights moving through a tube to some distant material body, like a cross between teleportation and long distance communication. Avatar is so embellished with interstellar cutting-edge media culture that one might be surprised to discover that it tells an anti-colonial tale of an indigenous population’s resistance to the exploitation of minerals on their home planet, Pandora, by invading Earthlings. As a political parable, it is a thinly veiled critique of imperial adventures by armed forces, ostensibly American in appearance and style (with at least one shot of “Old Glory” in the background). Bombastic dialogue about natives as terrorists and “shock and awe” tactics, take what might have been a John Milius film–for instance, Farewell to the King (1989)–and reframe it as a critique of the US invasion and occupation of Iraq.

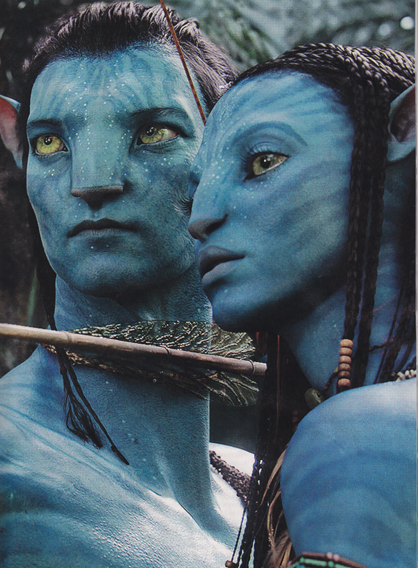

As influential as his work has been for non-conventional gender depictions, especially his muscularization of female action characters, the limits of Cameron’s imagination are apparent here in his racial politics. In Avatar, the species-specific divide presented on Pandora is recognizably driven by familiar earthbound notions of difference. Even as the drama directs audiences to cheer for the spiritually advanced and environmentally aware Na’vi, we confront stereotypical gestures and appearances of tribal peoples. Moreover, the actors behind the virtual costumes and make-up are suitably ethnicized to perform the “blueness” of the Na’vi. African-American actors CCH Pounder and Laz Alonso, and famous Cherokee actor Wes Studi, play lead Na’vi characters, and Dominican/Porto Rican-American actor Zoe Salanda plays hero Jake Sully’s love interest. Pointedly, only white folk, like our lead Sully, get to cross-over into specially cultivated Na’vi bodies. Sully’s story, then, is a “Na’vi like me” tale of passing. The core of the film is a “blueface” performance, which draws this film closer thematically to another “game-changing” film, the breakthrough talkie The Jazz Singer (1927), in which, in a way, Al Jolson’s stage persona is his racialized avatar.

The world of the noble savage offers ideologically safe contact with the natural and the archaic, that is, civilization’s Other. In Cameron’s case, the environmental ethos of the Na’vi, while reiterating the trope of nobility, is equally a way to present harmonious connections among all beings, using contemporary technological references to do so. Characters describe Pandora as a complex and complete data network, where even plant life has communicative capabilities. The Tree of Souls, the spiritual heart of the ecosystem, holds records of all feelings, expressions, and memories. It is, ostensibly, a colossal organic server. Flying into battle, individual Na’vi can communicate across distances by placing thumb and forefinger on either side of their throat, like a mimed handless mobile phone. Several scenes show the temporary intertwining of animal and humanoid as a kind of jacking-in of electrical filaments. Moments of this fusing are perhaps the most erotic renderings in the film, with abundant rolling eyes and pleasurable gasps.

As figured, the Na’vi are not merely figures of an ancient and superstitious worldview; like the technological tentpole commodity Avatar itself, the Na’vi offer an image of a superior technological system. Pandora is worth defending as an example of a natural data network and perfect synergy across beings and devices, with integration a racial, environmental, and technological concept simultaneously. The celebration of the peoples and creatures of Pandora is not a refusal of technological enhancement for some form of spiritual and environmental enlightenment, but a full acceptance of what might be called technological naturalism, that is an organic vision of an all-encompassing total media system.

The language of revolutionary change is a persistent feature in the film and media business. Never content with an existing apparatus, Hollywood has battled over formats, technologies, and processes as much as stars, directors, and movie franchises. Declarations of “game changes” and “revolution” are forms of competition at the level of hardware and software. In this way, an individual audio-visual commodity like Avatar, while working to entrench the dominance of key corporate participants, effectively continues a primary mode of investment in changing media materials and processes. The seizing of milestone moments is one way in which the very notion of technological change is made a comprehensible and vital part of our attention. At one level, even with all the local instances of innovation–and yes, to be sure, parts of the entertainment business are shifting dramatically–the language of “game changing” is another way to talk about business as usual.

Thanks to Zoë Constantinides for research assistance, and to Joseph Rosen and Haidee Wasson for inspiring conversation and commentary on the topic.

Image Credits:

1. James Cameron’s Avatar: Game-changer, or business as usual?

2. Publicity for Avatar from Twentieth Century Fox.

3. Newspaper advertising for Avatar.

4. Publicity for Avatar from Twentieth Century Fox.

Please feel free to comment.

- “Exclusive: Soderbergh gives Avatar high praise,” www.comingsoon.net, 30 April (2009). Cameron was a producer for Soderbergh’s Solaris (2002), so it’s possible there is a closer relationship than is evident from their different filmmaking personas. [↩]

- Quoted in Dana Goodyear, “Man of extremes: The Return of James Cameron,” New Yorker, October 26, 2009, 67. [↩]

- Bill Higgins, “All eyes on Avatar; fellow directors shower praise on Cameron,” Variety.com, 18 December (2009). [↩]

- Sharon Waxman, “Computers join actors in hybrids on screen,” New York Times, 9 January (2007): E7. [↩]

- Michael Cieply, “Eyepopping, in many ways,” New York Times, 9 November (2009): B1, B6. [↩]

- Josh Quittner, “The Next dimension,” Time, 30 March (2009): 54-62. [↩]

- Charlotte Huggins, “The Three dimensions of 3-D,” Produced By, Spring 2008: 25. It is curious that 3-D is being interpreted as a catalyst for digital exhibition because digital 3-D systems currently require screens that make their use for conventional 2-D projections darker, less sharp, and generally poorer in image quality. [↩]

- Matt Hurwitz, “Exposure: Vince Pace,” International Cinematographers Guild Magazine, April 2009: 30, 32, and 34. [↩]

- Chris Morris, “A Game changer?; Avatar looks to alter H’w’d vidgame push,” Variety, 15-21 June (2009): 4, 12. [↩]

- “Panasonic and Twentieth Century Fox team for global promotion of James Cameron’s Avatar,” Asia Corporate News Newswire, 21 August (2009); “Panasonic rolls with HD 3-D home theater truck tour,” Entertainment Close-Up, 5 September (2009). [↩]

- David Denby, “Big pictures,” The New Yorker, 8 January (2007), 54-63. [↩]

Charles – Thanks for a thought-provoking piece. In all the clutter and buzz over the film’s politics and awards hype, it is refreshing to read an industrial angle.

One highlight for me was an implicit question in your bringing up The Jazz Singer — what is it about these sorts stories of white male displacement that *literally* paves way for the formal technological vanguard? In other words, what is the connection between race/Other fantasy and industrial innovation? I would love to read more from you on this — what an unexpected confluence.

I appreciate your term “blueface,” as well. I have wondered whether Avatar is the ultimate example of a white male guilt/redemption tale told with utmost allegiance to a contemporary “post-racial” politics — so much so that, even though all of the “natives” are indeed portrayed by actors of color, racial difference needs to be subsumed into a pleasantly universal “blueness.” We can’t talk about race explicitly, so let’s just make all the “others” blue and call it a day.

I love your conceptualization, Charles, of technological tentpoles that “introduce and promote hardware media systems.” What I think is important to emphasize is that technological tentpoles provide opportunities that extend far beyond a single studio, conglomerate, or industry. It’s fascinating to see the range of players trying to hitch their wagons to Avatar’s star. The 3D TV manufacturers at the CES show in Las Vegas point to Avatar as proof for the insatiable public appetite for 3D. Jeffrey Katzenberg of DreamWorks, a competitor of Fox, uses Avatar to validate his slate of 3D movies. If a traditional studio tentpole is intended to exploit synergies across a conglomerate, then a technological tentpole enables the film to extend beyond the conglomerate and allows other companies and industries to appropriate the film’s success for their own purposes. In other words, there are multiple “games” that can be changed by a technological tentpole.

Since failures can be just as interesting as successes, I think it is useful to revisit DreamWorks’ Monsters vs. Aliens—a film that, while not a bomb, certainly failed to become the technological tentpole that its producers hoped. Back in 2006 and 2007, the entertainment press positioned the DreamWorks animated film as competing against Avatar for the bragging rights of which film would be the first 3D mega-blockbuster. (If you’ll remember, both Fox and DreamWorks had announced the same release date—Memorial Day weekend 2009—which neither studio ultimately wound up using for these films). When Monsters vs. Aliens opened in March 2009 to $58.2 million at the domestic weekend box office, the DreamWorks publicists worked hard to convince us that we had witnessed the game changer. Consider this Los Angeles Times article, “‘Monsters vs. Aliens’ is a hit in three dimensions”:

http://articles.latimes.com/20.....oxoffice30“

In the article, a DreamWorks exec said the Monsters opening “really proves the viability of the platform,” and a box office tracking executive commented that “this shows that 3-D is here to stay.” The hyperbole became painfully evident when just days later the less expensive and decidedly 2D Fast & Furious opened to over $72 million at the domestic box office. According to Weekly Variety, both pictures wound up grossing around $370 million in combined domestic-international box office, placing them outside of the ten highest grossing films of the year.

These numbers are less important than the overall point: that the technological tentpoles depend on both a primed publicity machine and the eventual appropriation of the work by a series of other filmmakers, companies, and industries. If Avatar had bombed, I am sure that Tintin or another 3D wonder would have allowed the studios, electronics industries, and other savvy businesses with a chance to identify and celebrate the technological game changer that promises to make them more profitable.