Thoughts from Oslo, Norway: Film Festivals and Expanding the Moral Imagination

Konrad Ng/ University of Hawaii, Mānoa

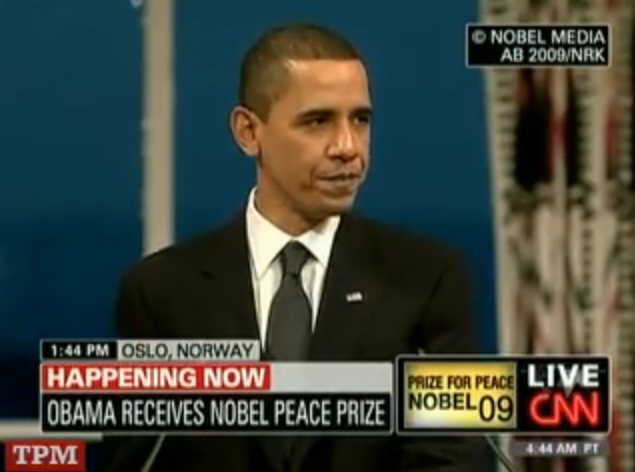

When U.S. President Barack Obama delivered his acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize, I was moved by his elegant response to the controversy surrounding the event and how he deftly addressed an issue that weighed heavily on his conscious. Was the award deserved for a President of a nation participating in two wars? Obama responded by suggesting that a morally tenable coexistence between war, peace and the exercise of American power was possible. He then offered an agenda for just war and just peace that accepted the notion that human fallibility is twined with human possibility. In the speech, Obama referred to President John F. Kennedy’s call to build “a more practical, more attainable peace, based not on a sudden revolution in human nature but on a gradual evolution in human institutions.”1 Such evolutions, Obama argued, involved a focus on “Agreements among nations. Strong institutions. Support for human rights.”2 Obama’s thoughtful speech deserves more detail than I will be able to provide here so allow me focus on Obama’s closing argument, which offered a line of reasoning that I found relevant to cinema.

The will required for “a more practical, more attainable peace,” Obama argued, relies on “the continued expansion of our moral imagination; an insistence that there’s something irreducible that we all share.”3 He states that

we all hope for the chance to live out our lives with some measure of happiness and fulfillment for ourselves and our families…[and] the one rule that lies at the heart of every major religion is that we do unto others as we would have them do unto us…The non-violence practiced by men like Gandhi and King may not have been practical or possible in every circumstance, but the love that they preached — their fundamental faith in human progress — that must always be the North Star that guides us on our journey. For if we lose that faith — if we dismiss it as silly or naïve; if we divorce it from the decisions that we make on issues of war and peace — then we lose what’s best about humanity. We lose our sense of possibility. We lose our moral compass.4

I quote this part of Obama’s speech in length to illustrate how Obama grounds the “continued expansion of our moral imagination” in faith, shared values and a politics of mutual recognition. The power of religion is, of course, undeniable, but I want to suggest another model of engagement that may help expand our moral imagination. The medium of cinema immediately comes to mind, but it is the film festival, I argue, that can be moral force. It is a tradition that has defined the industry of cinema yet remains an understudied form of cultural and political engagement. I suggest that the film festival can trace moral waypoints through the constellation of films selected for screening and acts as a useful exercise in community organizing and activism. Here, I am influenced by Michael Shapiro’s Cinematic Geopolitics (2009). In the book’s Introduction, Shapiro muses on the possibilities of film festivals vis-à-vis his experience as a juror for the Tromsø International Film Festival (TIFF), a lesser-known Norwegian event that embodies the spirit of the Nobel Peace Prize. During his tenure at TIFF, Shapiro was tasked with awarding the festival’s Norwegian Peace Film Award. Given the focus on peace, Shapiro observed that TIFF was a “cinematic heterotopia” that prompted him to reconsider his worldview and the critical possibilities of the world of film. TIFF was a space for scholars

involved in peace and conflict studies, those who organize film festivals, and those who make feature films and documentaries…[to deliberate] the anti-war, anti-violence merits of films from all over the planet and [bring] those deliberations into public dialogue with sizable audiences.5

Shapiro’s point is that film festivals can be a space for envisioning possibility and articulating critical attitudes towards acts of violence and oppression; film festivals can “provide a venue for films with significant anti-violence and anti-war themes and cinematic styles”6 and by doing so, assist the expansion of the moral imagination.

It is tempting to dismiss film festivals, especially large ones such as Cannes, Venice, Berlin and Toronto, as merely spectacle and glamour. While these large film festivals generate cultural wattage as a means of self-promotion, let me point to an example that has been the focus of my current research: the grassroots Asian American film festivals hosted by Visual Communications in Los Angeles , Center for Asian American Media in San Francisco and Asian CineVision in New York City. Founded through public grants and organized by filmmakers, these organizations have been the premiere curators, advocates and provocateurs of the Asian America experience for decades. Visual Communications, Center for Asian American Media and Asian CineVision have provided unique opportunities for critique, expression, promotion and coalition building on behalf of Asian America. Indeed, the critical representational practice, collegial ethos and grassroots nature of Asian American film festivals offer a counter-space to the commercial space of Hollywood cinema by playing a critical role in translating and transforming a notion of community into cultural and political engagement. Glen Mimura’s interview with scholar and artist Ju Hui Judy Han in Ghostlife of Third Cinema: Asian American Film and Video (2009) provides an excellent description of Asian American film festivals:

[T]hey are simultaneously a site of artistic expression and appreciation, social activity, political resistance, intellectual discussion, and commercial exchange. They provide a forum for artists to seek funding and wider distribution. They provide a forum for exchanging political information and engaging in debates. Film festivals are certainly invaluable in building a critical mass of people who can be counted on to participate in cultural community life.7

I contend that the curatorial activity, watchful commentary and community organizing of Asian American film festivals embody the political and cultural engagement described by philosopher Gilles Deleuze as “rhizomatic.” That is, the heterogeneity, juxtapositions, multiplicities and simultaneities of film festival practice form “connections between semiotic chains, organizations of power, and circumstances relative to the arts, sciences and social struggles…[they form] a throng of dialects, patois, slangs, and specialized languages.”8 This collective assemblage of cultural and political enunciation suggests that citizens can change in the world around them in novel ways. The cinematic heterotopia of Asian American film festivals offer an opportunity for moral engagement. The exhibition, advocacy and organization of minority films and subjectivities assists in the envisioning of alternate perspectives and experiences. The resulting enlarged mentality of film festivals can be a key ingredient in sustaining the desire for “a more practical, more attainable peace.”

My thoughts on the possibility of film festivals, particularly Asian American film festivals, as moral forms of cultural and political engagement will need to be fleshed out. Certainly, all that I have provided is a sense that there is more to film festivals than what is usually acknowledged in cinema studies and conventional wisdom. As a scholar who has worked as a film festival programmer and served as a film festival juror, during Obama’s speech I couldn’t help but think about how film festivals can capture and communicate the hope that drives “the world [as it] ought to be – that spark of the divine that still stirs within each of our souls”9; the cinematic heterotopia of film festivals, I suggest, can enable us to live by the example of others.

Image Credits:

1. Still from President Obama’s Nobel Peace Prize Acceptance Speech

2. Asian CineVision Logo

3. Asian American Film Festival Logo

Please feel free to comment.

- Barack Obama, “Remarks by the President at the Acceptance of the Nobel Peace Prize” (White House, December 10, 2009), http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/remarks-president-acceptance-nobel-peace-prize (accessed December 10, 2009 [

]

- Ibid. [

]

- Ibid. [

]

- Ibid. [

]

- Michael J. Shapiro, Cinematic Geopolitics (New York: Routledge, 2009), 34. [

]

- Ibid., 33 [

]

- Glen Mimura, Ghostlife of Third Cinema: Asian American Film and Video (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 124. [

]

- Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Trans. Brian Massumi, (Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press, 1987), 7. [

]

- Barack Obama, “Remarks by the President at the Acceptance of the Nobel Peace Prize” (White House, December 10, 2009), http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/remarks-president-acceptance-nobel-peace-prize (accessed December 10, 2009 [

]

Pingback: Thoughts from Oslo, Norway: Film Festivals and Expanding the Moral … city university

Sorry for the delayed response, I only found the link from a mention by Taro Goto, the former Associate Director of the San Francisco International Asian American Film Festival that is presented by CAAM. I had very much enjoyed the President’s Nobel acceptance speech, and saw in the related media references to Reinhold Niebuhr, the connection to his morally focused and pragmatic approach to his legislative and diplomatic change. But I had not made the connection to film festivals that Konrad has, a connection that I find provocative and convincing. There are many kinds of film festival, course. Some of the largest are integral to the marketing and distribution of cinema as entertainment. Some at the other end are more geared toward civic boosterism. Our sector, and one shared by dozens, if not hundreds of other culturally specific festivals, reflect, as Konrad asserts, an important connection to a cultural or identity-community, and as such, play a key role in the continued evolution of the community and its place within the larger world. Thanks Konrad for broadening the aspirational context for our work. And see you at the movies!

Konrad: As Stephen has characterized, what a rich, provocative and convincing connection you have made here between grass roots community-based festivals and the moral compass they provide within the broader context of film festival culture. I certainly concur and applaud this focus. I look forward to sitting down with you when you are in San Francisco for the upcoming edition of CAAM’s San Francisco International Asian American Film Festival to discuss this topic in more depth. For starters, you might be aware of the efforts of Asian American filmmakers Eric Byler and Annabel Parker and their Facebook “Coffee Party” project: an inspirational blend between activist documentary filmmaking, social networking, and grass roots activism?

Thank you so much for the intelligence and articulation you’ve applied to this aspiration.

A sad day for the world when this man-child receives the Nobel Prize.