Threat or Treat: Film, Television, and the Ritual of Halloween

“I killed him!! I’m the most horrible!”, yells Tootie, as she runs away from the Braukoff house, charcoal on her face. The scene is from Meet me in St. Louis. The film shows just how crucial the seasonal holiday of Halloween is to feeling at home or alienated in a community. In 1904 St. Louis, Tootie, played by Margaret O’Brien, roams her neighborhood after dusk, dressed up as a ‘horrible ghost that died of a broken heart’. She joins other unsupervised kids around a giant bonfire, and she scares the wits out of neighbor Braukoff, whom she suspects of ‘burning cats at midnight in his furnace’, and of having empty whiskey bottles in his cellar. Much of Tootie’s Halloween resembles our own, many decades later. But much has changed too.

In this, the first of three columns on cultist rituals, media culture, and senses of ‘belonging’ in what is best called – and limited to – ‘today’s Western world’, I am looking at the cult of Halloween and its appropriation by the horror industry. The next columns will address the Yuletide season, and Valentine’s Day. Each time, the stress is on the impact of today’s media culture on how ‘we’ (or I, at least) make use of seasonal and cyclical festivities and remembrances to help give sense to our lives.

Tootie’s adventure captures the essence of the Halloween holiday perfectly. It is a little bit frightening but it is also fun. It is a feast, a flaunting of social taboos, and an exercise in testing one’s fears. Halloween tests the boundaries of a community’s sense of togetherness and its ability to recognize strangers and predators. Through dressing up we check our capacity to tell true danger from fake scares, and to signal both our friendliness and test that of others – if we can be recognized as friendly even when we wear a mask we must be in good company (note how it is charcoal in the case of Tootie).

The function for the Halloween cult’s mix of fear and fun is threefold. The first is the commemoration of those who perished in the community’s tough Summer-labor of bringing in the harvest and preparing for the survival of Winter – hence the emphasis on imagery of death. Halloween’s second element involves an orgiastic bonfire consumption of abundance; treats are generously shared with neighbors. Finally, there is also an element of threat. The leftover harvest that cannot be stored or consumed needs to be destroyed, or it will attract predators. The community’s ability to distinguish between neighbors and predators, between friends and foes, is tested severely during the Halloween period – is that shape over there just an inebriated neighbor or a predator? Various customs have appropriated parts of Halloween… Many of these are important holidays, but they don’t carry Halloween’s exhilarating mix of thrills and fears.

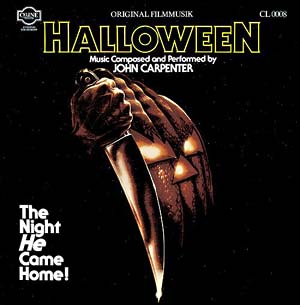

That mix is preserved perfectly in the horror movies that have become so ubiquitous for Halloween. In 1978, John Carpenter’s appropriately titled Halloween, set in a neighborhood not unlike that of Meet me in St. Louis, demonstrated that the holiday matched the concerns of modern horror cinema. At the time, the genre was going through a big transition. Stories about old-school monsters (counts from faraway castles) were being replaced by stories about the ‘horror within’, the evil amidst the community, among your friends and family. Surviving horror in those stories really became a test of knowing your friends from your foes – exactly the essence of Halloween.

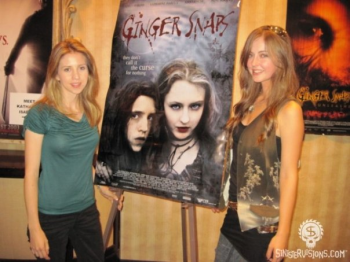

The success of this transition catapulted what had been a subculture of horror into a massive industry, so much so that critics such as Lawrence O’ Toole and Robin Wood referred to the late 1970s as the ‘cult of horror era’. Propelled by Halloween’s massive success, the period between the end of October and the beginning of December quickly became a preferred release period for the renewed genre. Many of horror’s modern classics premiered around Halloween: from Evil Dead, Stephen King adaptations, and many of the Michael, Freddy and Jason franchises, via The Blair Witch Project, Ginger Snaps, Saw, to Paranormal Activity, … and even Michael Jackson’s “Thriller!”

But something changed too. As seasonal activity became central to the success of the horror genre, Halloween became more popular as a cultural vehicle for everything from heavy metal album releases and horror fanzines such as Fangoria to video clips. Since the 1990s, television has taken a huge interest in the holiday, from shows such as Tales from the Crypt and channels such as Chiller TV, to sports broadcasts to animated comedy. The presence of bonfires and log fires on community channels are clear evidence that the interlinking between the original ritual and the media cult, between Halloween and Halloween, has dissipated. ‘Halloween’ now supports, and is supported by, a big chunk of the entertainment industry. It has become over-cultified. Its rituals are more those of media audiences than those of communities interrogating their cohesiveness and hospitality. Many of the horror films that set the tone for the transition have recently been re-born or re-vamped, and this cycle of recycles has created some form of overkill. Halloween is now a product, an image, and no longer an event.

Against that stand a few occasions that resist this detachment. Let me stress just one example. Last weekend I attended the Flashback Weekend Chicago Horror Convention, the longest surviving in the area. Sponsored by Anchor Bay, offspring of the cult of horror, and run by die-hard lovable showman Mike who have their roots in the drive-in business, it stresses the personable in Halloween’s rituals of feast, commemoration, and friend-or-foe testing. Above all, it carries at its heart a sense of direct contact, present most obviously in the meet and greet sections of the convention but also in the fake scares of the macabre costume parties and contests, and in what can really only be called a genuine sense of community – family, kids and all. And guess what, when Evil Dead’s Bruce Campbell, Nightmare’s Robert Englund, Aliens’ Lance Henriksen, and the Ginger Snaps sisters show up, so do 2,000 fans, who party ‘till dawn.

In the 21st Century, our thirst for testing who our friends and foes are has taken on new dimensions. The tightly knit communities of yore and even the suburban neighborhoods of Halloween are joined by a global village in which everyone is in touchpad reach of everyone, and in which “everyone’s a suspect”, as Randy yells out in Scream. These changes might become the ultimate test for the tradition: where does the cohesion of a community lie if every member is under suspicion? And what am I going to dress up as if everyone’s a ‘friend’ or acquaintance? As the ghost of evil corporations? Does it imply that, to paraphrase Tootie, the “most horrible” may indeed be me? Or does it obliterate the function of Halloween, reducing it to merely an occasion to ‘let loose’, as the punk band The Dead Kennedys shout in their criticism of the holiday?

I put my faith in Meet me in St. Louis. In much the same way traditions of tactility (by which I mean traditions in which people actually go face to face, and maybe even touch each other – from shaking hands to full embraces), refuse to be shoved aside by modern technology in that film there will always be a purpose for a cyclical seasonal festivity that highlights both evil and pleasure, both the horror of fear and death and sumptuous consumption, generosity and ‘lettin’ loose’. For that mix, the physicality of horror is perfectly suited. Donnie Darko-creepy-bunny-suited.

Image Credits:

1. Tootie says “I’m the Most Horrible”

2. John Carpenter’s Halloween

3. “Thriller”

4. Ginger Snaps Reunion at Chicago’s Flashback Convention

5. Donnie Darko

Please feel free to comment.

I could not help but think about the transition Halloween goes through for everyone as we mature from child to adult. As a child I always felt more of the community orientated notion of Halloween. However, there were a few years there where Halloween was about media as I sat in some high school classmate’s dark basement with friends watching HALLOWEEN, FRIDAY THE 13TH, and NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET. Now, as an adult, it seems that Halloween has returned to its community roots as adults hold parties and it becomes a celebration, although a morbid one.

Thanks for your reaction, Sam!

I agree, and I have had the same impression. I wonder if (IF) it matters if (again, IF) we consider Halloween within the framework of ‘cult’ (cultist ritual, cult movies, …) — cult movies and Halloween celebrations are both often regarded as child like, and it could be said we outgrow that (and cult movies outgrow that) by becoming media savvy. I wonder if the ‘return’ to community at an older age has a parallel too? Return to the classics? Or an incorporation of notions of ‘commemoration’ and ‘remembrance’ into the celebration?

That said, a parallel is not an explanation. Though I still feel there is something more there.

One more thing: I think I should have added to the function of ‘commemoration’ also the remembrance of the labor of seasonal workers cast out of the community after their labor is done.

Ernest

What a great (and timely) article! What I like best is the way that you’ve isolated this moment (of authenticity, let’s say) and demonstrated how it has become part of our ‘natural’ perception of the holiday/event.

In terms of the ‘cult’ aspect, I guess my question is more philosophical . I wonder if there is a way that we can recapture our inner “Tootie-ness” rather than merely participate in the savvy, mass-marketed aspects of the holiday? Alternatively is it possible that the market (rather than the “cult”) positively facilitates our participation in the genuine feelings of the original event?

Thanks again! I’m looking forward to the Christmas version!

Colin

You bring up many interesting points about Halloween. Meet Me in Saint Louis is great in that it shows us a pre-trick or treat celebration, which is more like what we in PA called ‘Mischief Night,’ the night before Halloween when kids toilet paper trees and soap cars and egg houses, ring doorbells and run, et al. That was the time when the real halloween ran amok.

I’d say in defense of the neighbor who gets flour in his face in MMISL that he’s ‘in’ on the game – acting outraged, menacing, shocked, etc. as a performance of a role for the community’s benefit. Conscious or not, we all as Shakespeare wrote, play many parts in our long life, and this guy perhaps did similar ‘most horrible’ things to neighbors, and is now receiving his own malice, so to speak, and by performing the looming monster reduced to motionless shock by some tossed flour, he aids Tootie’s development. None of this is ever stated of course, but I think it’s there in the subtext.

I wonder about the Irish traditions involved?

Mention of banshees?

Dress up and mischief making are very Irish?

But the family is not notably IIrish, perhaps assimilated beyond recocognition?

Thanks