A Look Back at Michael Jackson

Konrad Ng / University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa

I was in Beijing when CNN International broke the sad news: Michael Jackson had died. Just a week earlier, my wife and I had introduced Jackson’s music to our 5-year-old daughter. In between songs from albums, Off the Wall (1979) and Thriller (1982), we praised Jackson’s extraordinary talent, offered examples of his contributions to American pop music, and touched on some of the tragedies that had haunted his life. The King of Pop was a beautiful soul who broke records and barriers. His music and recognition crossed borders and cultures. He pushed popular understandings of race, gender, sexuality and spectacle in entertainment and music. Jackson’s behavior and appearance was complicated and at times, perplexing and painful, yet there was certainty that his music would endure. The entirety of Michael Jackson’s life was a lot to digest for a young mind, so we just danced to his music. My wife and I relished the nostalgia brought on by Jackson’s music and experienced feelings of bliss as we watched our daughter bust a move.

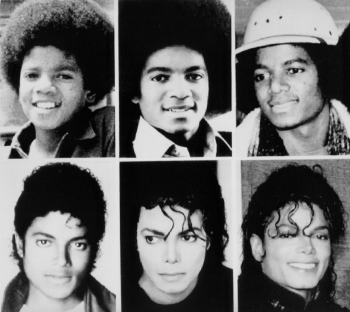

When I was a teenager, Jackson was important to me. I appreciated his music, of course, but there was something about the sense of ache and misunderstanding in Jackson’s widely discussed and much observed transformation in appearance that provided insights for my own journey with race. The ambiguity that emerged from speculation about Jackson’s racial appearance felt familiar: Was Jackson, a Black man, trying to become White? Did he hate his Blackness? Did Jackson really have a skin condition as he had stated on numerous occasions? I found that Jackson’s racial liminality resonated with my experience with Asian-ness. For some, Asian-ness in North America has involved a balancing act between cultural fidelity and national belonging. The questions that are often asked can be indelible: What are you? Where do you come from? These questions prompt self-reflection on the meaning of Asian-ness in one’s sense of self as well as a consideration of what parts may be considered “non-Asian.” When I saw Jackson, particularly during the release of the album Dangerous (1991), he was someone becoming paler, his hair was becoming straighter, and he increasingly wore heavy make-up and eyeliner that gave an almond-like shape to his eyes. As a teenager pressed to answer questions about my racial identity, I felt a sense of Afro-Asian kinship with Jackson. Jackson’s untimely death prompts me to consider what he meant to me. I want to treat Jackson as a point of departure for a brief discussion about contemporary work in the aesthetics of racial identity in America.

Cultural theorist Kobena Mercer (1994) offers a terrific reading of Jackson’s music video, “Thriller” (1983), and its relationship to the ambiguity that came to define Jackson’s racial, gender and sexual identity. Mercer contends that the spectacle of Jackson’s indeterminate status as someone who was “[n]either child nor adult, not clearly either black or white, and with an androgynous image that [was] neither masculine nor feminine” is acute when considering how “Thriller” parodies his ambiguity.1 Mercer contends that the genre, narrative and style of the music video, which stood out for its cinematic characteristics at the time, directs attention to the mythology of Jackson’s ambiguity as he “enact[ed] a variety of roles as the video engage[d] in a playful parody of the stereotypes, codes and conventions of the horror genre. The intertextual dialogues between film, dance and music which the video articulates also draw us, the spectators, into the play of signs and meanings at work in the ‘constructedness’ of the star’s image.”2 As a consequence, the video highlights how uncertainty in racial and sexual performances raise questions about received notions of identity. In the case of a megastar like Jackson, his ambiguity destabilizes popular beliefs about the appearance and behavior of black male artists. Mercer contends that Jackson’s ambiguous agency “not only questions dominant stereotypes of black masculinity, but also gracefully steps outside the existing range of ‘types’ of black men.”3 I think that a similar dynamic is operating in Jackson’s music video, “Black or White” (1991).

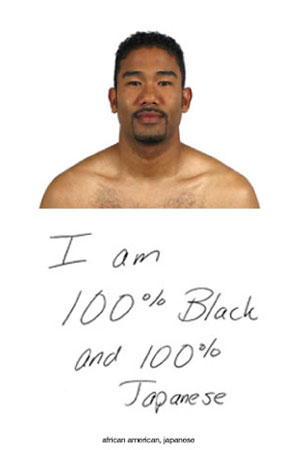

“Black or White” reunited Jackson with “Thriller” video director, John Landis. The song’s message about race, “If You’re Thinkin’ About My Baby, It Don’t Matter If You’re Black Or White,” is conveyed by the video’s visual harmony of cosmopolitan, humanism, multiculturalism and multiracialism. Here, I want to focus on one particular sequence in the video: the multiracial/multicultural/multi-gender morphing montage. Near the end of the video, after Jackson has joined African, Southeast Asian, American Indian, South Asian and Russian dancers dressed in native, traditional, tribal or religious clothing, there is a montage of men and women from different racial backgrounds standing against a neutral backdrop. The people happily dance and sing to “Black or White” and appear to be topless, revealing only their head and shoulders. The sequence stands out for its comment on race and gender and its example of computer generated imagery as the men and women seamlessly morph into each other. It is possible to read the montage as a statement that Jackson’s race should not matter because we share a common humanity. For me, however, the seamless transition between these faces of different races and genders set to the song’s chorus prompts the viewer to adopt an attitude of resemblance and by doing so, entertain the thought that race and gender are permeable concepts. Viewed within the context of popular interest in Jackson’s indeterminate agency, the video can be read as making a statement similar to Mercer’s thoughts on the possibilities of “Thriller”: Jackson reframes the discourse of black male identity by inhabiting a narrative in which race and gender are intersections as opposed to being discrete codifications of performance.

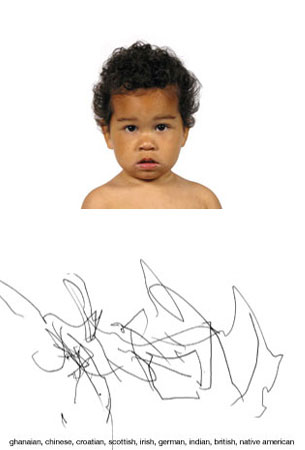

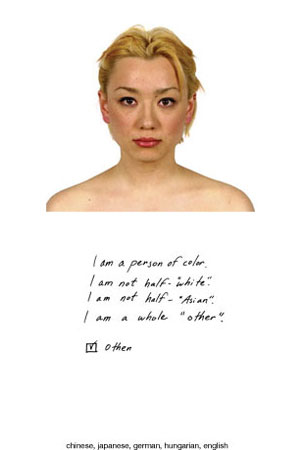

I focus on the morph sequence in “Black or White” because it makes me think of artist Kip Fulbeck’s The Hapa Project and his portraits of mix-raced people in the project’s book, Part Asian, 100% Hapa (2006).4 Similar to the ways in which the men and women are framed during the morphing montage in “Black or White,” Part Asian, 100% Hapa contains photographs of men and women from mixed racial backgrounds standing against a white backdrop. The models also appear topless, revealing only their head and shoulders, but they hold neutral expressions. Each portrait is accompanied by a list of the model’s racial and cultural background and a written statement that muses on the dynamics of their identity. Rather than consider the happy resemblances between the men and women in “Black or White,” Part Asian, 100% Hapa presents a restrained atmosphere that asks viewers to discern and ponder the features and attitude of the model in relation to preconceived notions about race, gender and their inter-articulation. The book suggests that the kind of polemical indeterminacy that haunts Jackson’s agency is the experience of these “hapa” or mix-raced models.

Fulbeck’s interesting work takes on added significance if we heed the latest U.S. Census Bureau projection that America will become more Asian, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, American Indian, Alaskan Native, Black, Latino and mixed in attitude and make-up over the next fifty years. By 2023, minorities will make up more than half of children being born and by 2050, America’s former minority communities will become the majority and the population of multiracial people is projected to more than triple its current number.5 As we embark on this journey towards a more diverse America, artistic expressions by minority and mixed cultural and political workers will be crucial to changing the meaning of the two question that many of us are asked today: What are you? Where do you come from?

Image Credits:

1.) Michael Jackson’s hit single, “Black or White”

2.) The Changing Face of Michael Jackson

3.) Facial transformation in the video for “Black or White” – Author screen captures

4.) Images from Kip Fulbeck’s “Part Asian, 100% Hapa”

Bibliography

Mercer, Kobena. Welcome to the Jungle: New Positions in Black Cultural Studies, New York: Routledge, 1994.

Fulbeck, Kip. Part Asian, 100% Hapa. Vancouver: Chronicle Books, 2006.

Please feel free to comment.

- Kobena Mercer, Welcome to the Jungle: New Positions in Black Cultural Studies (New York: Routledge, 1994), 35. [↩]

- Ibid., 38. [↩]

- Ibid., 51. [↩]

- Kip Fulbeck, http://www.seaweedproductions.com/hapa. Part Asian, 100% Hapa is also a traveling photography exhibit that opened at the Japanese American national Museum on May 30, 2006, http://www.janm.org/exhibitions/kipfulbeck. [↩]

- U.S. Census Bureau, “An Older and More Diverse Nation by Midcentry” (U.S. Department of Commerce, August 14, 2008), http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/releases/archives/population/012496.html (accessed August, 14, 2008). [↩]

Now you get appnana hacker from here completely free of cost.