The Myth of Online TV

Christine Quail / McMaster University

Some students, young professionals, and techno-savvy viewers are foregoing cable subscriptions and choosing to access TV programs in non-traditional manners. Portable screens, mobile watching, and an on-demand, in-control screen culture are ensuing. Quite a number of academics and journalists, as well as product developers and marketers, have picked up on this trend and have begun probing the relationship between changes in technology and changes in viewing practices. Some would go so far as to proclaim the death of TV, as “everyone’s doing it” and “you can get what you want, when you want it” becomes the mantra of the next generation.

However, there are several concerns that must be addressed when one is tempted to proclaim TV dead. Besides the obvious point that media formats exist even after new technological developments (books are still around, after all), here are a few points to consider regarding several blind spots in the enticing TV streaming and downloading myths.

1. “Everyone watches TV online”—They Myth of Ubiquitous Internet Television Viewing

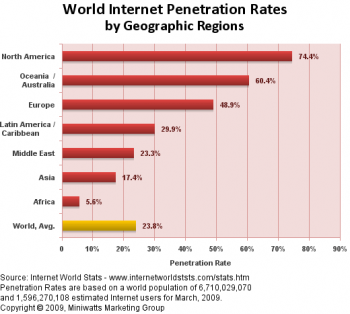

International Telecommunications Union (ITU) research suggests that the digital divide is still strong. Consider the following statistics. The global Internet penetration rate for 2008 was only 23%–meaning, only 23% of the world’s population has access to the internet, and in some parts of the world, this access is in a public forum such as a library or Internet cafe, not on a hand-held device or laptop computer.1

Of course, the so-called developed world fares better than the “developing” nations, with 55% people are online in the former and only 12.8% in the latter.2

Regionally, it is unsurprising that North America has 73% internet penetration

Australia/Oceania 59.9%

Europe 48.5%

Latin America/Caribbean 29.9%

Middle East 23.3%

Asia 17.2%

Africa 5.6%

So, only 5% of Africans use the Internet—mostly in public settings such as Internet cafes, with mobile and broadband infrastructure overall as “negligible.” Geography also helps structure this context, with coastal countries’ access to undersea fibre optic cables affording them greater bandwidth that might be needed to access BitTorrent, or even Realtime or Windows-based videos.4 Access to Internet, then, does not mean watching TV online, either in the potential to download, nor actual downloading practices.

Beyond the global digital divide, in-country divides are significant. For example, in a recent presentation at the Canadian Communication Association, Nikki Porter demonstrated that within Canada, only 2% of the population relies on the Internet for TV, with young people and those with higher incomes more likely to view online content. Porter has dubbed this the “prime-time digital divide” and maintains that we don’t live in a “post-scheduling” world–that the technologically centered class, age, education differences still mean that network scheduling, and ostensibly advertising, is still important. In her words, the hoopla over online viewing claims are “based on statistical outliers,” succinctly naming this part of the myth’s equation.5

The same in-country divides could also be applied to each of the above countries–Internet access and computer ownership is tied to income, wealth of the country, social status, educational and skill level, and age. This provides a multi-tiered global divide of users.

While user-based statistics tell an important, and oft-neglected part of the story, the story is incomplete without also asking, what media-side and policy-side forces are causing differential, unequal access?

2. “You can get what you want, when you want it.”–The Myth of User Control

This part of the equation takes away all power from the media conglomerates that choose what to produce, how to produce it, and only then, what to put online–and where, and how. Television programs are a lucrative form of intellectual property for copyright holders, and corporate decisions about online access are not made lightly.

On official TV websites, content can be, and often is, made readily available. This is not the original model–networks took time to warm to a web presence, but decided that they had to incorporate the new technology to keep and grow viewers who were going online and would eventually go off-network to “illegally” access programs. Spoilers were a concern, but the real issue was ratings and the ability of networks to command advertising dollars and thus profitability (a la Viacom vs. Google over YouTube uploads, and the recent Pirate Bay ruling in Sweden).6

Various distribution deals are made beyond simple network postings, and each deal is a unique legal contract with its own terms and conditions. Blockbuster made a deal to distribute a digital movie library through TiVo (not to the entire population, just to TiVo subscribers), which structures access to that content.7

Even on pay sites such as iTunes, contracted deals are made between copyright holders and the distribution sites–you can’t just get “whatever you want.” NBC was unhappy with iTunes’ 99-cent-fits-all download price, and for almost a year removed its popular programs such as The Office and 30 Rock from iTunes’ catalogue. After Apple decided they would allow NBC to charge a higher price for HD programs, NBC returned forcing Apple into a tiered-fee policy.8 NBC recently commented that they actually earn more money from free download sites than on pay-per-downloads such as iTunes, due to the advertising revenue gained by delivering so many free-TV-show seekers. This is a healthy reminder that the “real” audience for TV shows is often the advertisers.

Similar restrictions to content apply to webcasting consortium Hulu, jointly owned by NBC Universal, News Corp. and Providence Equity Partners (a private equity firm), and soon to be joined by Disney, who had previously refused to engage a variety of online video platforms, including Hulu. Now, Lost, Desperate Housewives, and Disney kids’ and youth programming will be available.9 is still not possible to download CBS or CW programming on Hulu—CBS’s own online content provider, CBS Interactive, is in fierce competition with Hulu, thus not sharing its content with its rival.10

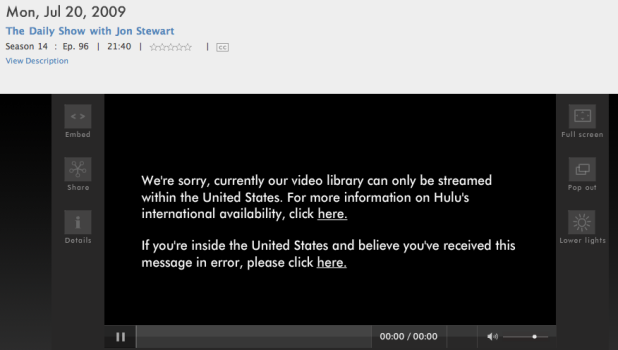

Further, online availability varies by country–from network sites to pay-per sites. In Canada, iTunes is relatively new, partly based on having to negotiate separate content deals from its American division. iTunes Canada’s director of marketing, Peter Lowe, states: “‘It’s complicated because different networks and production companies have rights to content in different places around the world and you ultimately have to work with the person who owns the content to deliver it….Unfortunately, there is no one rule that you can apply.’ In the United States, Apple and Microsoft typically negotiate download deals directly with a television show’s producer. In Canada, however, television networks often hold the internet rights to shows, which adds a layer to negotiations.”11 In Canada, programming is mostly available on Bell Canada’s Bell Video Store, and Microsoft’s Xbox Live. Hulu–the entire site–is not available in Canada, nor is YouTube’s streaming of ABC programs.12

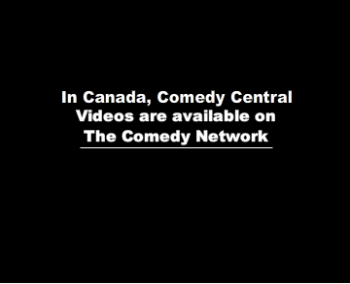

It is impossible, even, to download The Daily Show from Comedy Central’s website while in Canada. If you attempt to do so, you are immediately redirected to the Comedy Network page–the home of Canada’s cable comedy channel, owned by giant CTVglobemedia. While Comedy Central is not carried in Canada, Viacom has an exclusive distribution deal with the Comedy Network for the entire Comedy Central library, including The Daily Show, and including online streaming content. 13 Just as some American content is internationally limited, so, too, is Canadian content. For example, the CBC drama Being Erica, airing on CBC (and co-produced by CBC-TV and Temple Street Productions), is distributed internationally by BBC Worldwide, and leased in the U.S. not by a major network, but rather by SOAPnet (owned by Disney), which is most well-known for playing reruns of soap opera programming.14 Online streaming content for Being Erica, is available on the CBC website from within Canada only, but SOAPnet does not stream video of the program–it’s not part of their distribution deal. Again, each deal creates another layer of structure to access.

Some governments also structure access–China simply decided to censor YouTube in March 2009 claiming political propaganda, but rather than block an individual video, the entire site was disabled, thus blocking all content to all videos.15

If you can’t get “what you want” through official channels, why not simply “pirate” it (or liberate it, depending on your philosophical position)? The ability to circumvent “legal” mechanisms and utilize other approaches for locating and downloading programs is premised on the fact that first, one wants to do so, second, that one knows how to do so, and third, that one is technologically equipped to do so. Students in Canada are only briefly miffed that they can’t watch The Office online at NBC because of international distribution deals. They say they can simply download it by using a proxy server. The ethics of P2P TV and fears of being sued have been articulately addressed by Michael Newman in an earlier Flow article (2009), and is worth reiterating here. Additionally, the educational and technological privilege (tied to class) is also a factor here. Not “everyone” will circumvent blocked content.

3. “Television is dead.”–The Myth of the Post-Television Era

If you agree that online viewing is ubiquitous, and that you can get whatever you want when you want it, you might be prone to think that television is dead.

While we can point to the development of web-only content, such as extra webisodes of network programs, or made-for-Internet series, such as Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog (which, not coincidentally, is produced by Buffy producer Joss Whedon and stars the cultishly popular actor Neil Patrick Harris), television is still a multi-billion dollar industry, a major distribution outlet for film, new TV content, news, sports, and educational programs. Advertisers still spend billions of dollars trying to reach consumers, and the ratings industry and programming execs still try to find new ways to count viewers to deliver to the advertisers. Union and non-union labor still work to produce shows, and producers/owners attempt to find ways of reducing costs and thwarting union organizing.

Besides, the “liveness” of television is also still a factor that has not been replaced by “on-demand” content. And local news and community access, while continuously threatened, are still a central feature of the TV system in a democratic society.

Add those points to the information discussed above, and there seems to be a pretty strong case that television is still alive and kicking–though possibly not “the same as it ever was.”

I am not attempting to argue that screen cultures shouldn’t be studied, or we shouldn’t give thought to the politics and experiences and implications for accessing TV in new-media ways—that would be absurd. I am simply bringing (back) into the conversation what I see as key issues that should be kept in the conversation as it proceeds—that within the political economy of global television, new technologies can facilitate and constrain, largely at the hands of the large conglomerates and that dominate the media landscape.16

Image Credits:

1. Hulu logo

2. Regional Internet Access Rates

3. NBC program The Office on an Apple iPhone

4. Notification of Hulu’s Unavailability in Canada

5. Message from comedycentral.com in Canada

Please feel free to comment.

- ITU. “Information society statistical profiles 2009: Africa.” International Telecommunications Union. 2009. [↩]

- ITU. “Measuring the Information Society.” International Telecommunications Union. 2009. [↩]

- Internet World Statistics. “World Internet Users and Population Stats.” 2008. [↩]

- ITU. “Information society statistical profiles 2009: Africa.” International Telecommunications Union. 2009. p. iii. [↩]

- Porter, Nikki. “Time-Shift: Has the Digital Divide Come to Prime-Time Television?” Canadian Communication Association Annual Convention. Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario. May 29, 2009. [↩]

- Sullivan, Tom. “Pirate Bay not necessarily a victory for Hollywood,” The Christian Science Monitor. April 29, 2009. [↩]

- Stone, Matt. “Blockbuster and TiVo join to deliver digital movies.” The New York Times. March 25, 2009. [↩]

- See: Stelter, Brian. “NBC shows will return to iTunes,” The New York Times. September 9, 2008; Barnes, Brooks. “NBC will not renew iTunes contract,” The New York Times. August 31, 2007. [↩]

- Shields, Mike. “Will CBS, The CW heed Disney’s call to join Hulu?” MediaWeek Vol 19 (18): 6. May 4, 2009 [↩]

- Shields, Mike. “DIGITAL.” MediaWeek Vol 19 (19): AM9. May 11, 2009. [↩]

- CBC. “TV download battle finally begins in Canada.” CBC.ca. December 12, 2007. [↩]

- CBC. “Canadian iTunes store adds U.S. prime-time shows.” CBC.ca. May 28, 2009. [↩]

- CTV. “CTV Strikes Multi-Platform Content Deal With Comedy Central.” June 27, 2007. [↩]

- SOAPnet. “Being Erica.” 2009. [↩]

- Helft, Miguel. “YouTube blocked in China, Google says.” The New York Times 24, 2009. [↩]

- Quail, Christine. “Smoke Screens: Screen Culture Roundtable.” Visual Culture Symposium: Unthinking Television. George Mason University, Fairfax, Virginia. March 26, 2009. [↩]

Thanks for the interesting article, Christine! You raise some great points about the privileged assumptions inherent in these myths.

I’m curious as to what you think is driving and perpetuating the three myths you list–particularly the last one. Is it just the novelty of “the next big thing”? The fantasy of a more democratic media? In other words, what’s the appeal of the death of television?

Christine,

I like that you have shattered some of the major assumptions that I find myself discussing in classes, particularly the pesky issue of the remaining digital divide and the increasingly divided content which seems to be cordoned off – reinforcing, rather than shattering national borders.

As an ex-pat attempting to subvert some of the channels that you describe – it is impossible for me to watch Canadian content here through the “proper channels”, nor can I share American programming with Canadian friends – I’m happy that you highlighted some of these major issues of the increasingly disconnected (rather than connected) world wide web.

Colin

Great article Christine.

I have been thinking about some of these questions—also raised in the recently published volume Television Studies After TV—too.

This issue of access is really important, and it also raises questions about the myth of the disappearance on the “nation” within television production and consumption practices. Clearly these are still important not only in relation to what gets made, but who can see it and where/when.

There’s some kind of link here to Serra Tinic’s recent piece about Canadian TV and the lack of reruns we have here. There’s a LOT of Canadian TV that you can’t get anywhere not matter how much you want it. And all of this also connects, in my mind and for my own work, to the question of visibility, access and television studies that focus on text. How can we talk about texts that have severely limited circuits of distribution and circulation—not just on “TV” but online?

Sorry for the scattered nature of this post,

M.

Pingback: Television & American Culture Syllabus | anne helen petersen

I am not surprised that the U.S. internet intake is at such a high rate! I feel that we are becoming too dependent on the internet’s use!! Don’t get me wrong, I find the internet to be beneficial, but people rely on the internet more than they should! Sometimes people find anonymous news articles, and instead of questioning the origin of the information, several internet viewers place heavy reliance on the material. There is a higher chance, however, that TV will have more credible information. For example, if you go online, people may have submitted an article on wikipedia about a recent occurrence, such as Obama’s recent apology to Afghanistan. Wikipedia has a reputation of allowing anyone to submit information on their website. Bearing this knowledge, how do you know if the site is telling the real story? If you go to a trustworthy TV source, such as Fox News, the probability of receiving accurate facts about Obama’s apology. You cannot always place reliance on the information that TV provides.

The internet is not entirely bad, in fact there are several benefits. People can sometimes gain access faster through the internet. Sometimes, people can watch important programs, such as the news. As mentioned in the previous paragraph, people should monitor the website where one has gained the information. Internet TV can allow people to watch other shows, such as The Walking Dead. People can instantly download the episodes, instead of going to the store and buying the desired episode(s). Internet TV can be helpful, in allowing people to watch certain shows on their own time.

Bonsoir, Merci pour votre article. j’apprecie votre style. Auriez-vous des forums ou blogs a me recommander.