Soft Selling Intergenerational Intimacy on the First Season of Mad Men

Leigh Goldstein / FLOW Staff

Sheepishly, I’m going to admit disappointment at the absence of a media controversy. I’m mourning the lack of outrage at the Glen Bishop – Betty Draper friendship from Season 1 of Mad Men. It’s not that I bear any ill will towards Matthew Weiner, or Marten Weiner and January Jones (Glen and Betty, respectively) or really anyone else involved in the production or promotion of this show. Yes, I was sort of hoping a career or two might be threatened (even destroyed) by the taint of a pedophilia panic. But no personal vendettas were motivating my dreamy visions of newspaper columns blasting the show for hinting at a sexually charged rapport between a nine-year-old boy and twenty-eight-year-old woman. Or my fantasy of some treasure trove of fan posts, each one a variation on general admiration for the show regretfully tempered by disgust at the Betty-Glen rapport. Nope, no personal ire. Just your average, would-be crusading grad student’s desire to unmask (and ridicule) public discomfort at the representation of children as sexualized beings.

Disappointment acknowledged, I am ready to marvel at the skill with which the Mad Men people have constructed this particular relationship. Betty (to clarify for the uninitiated) is the very beautiful and very isolated suburban wife of Don, the show’s central character. The death of her mother is revealed in the second episode of the series, and throughout the first season, the emotional disconnection between her and Don is highlighted. Beyond her therapist and a female friend, the only person she is shown confiding in is Glen, the nine year old son of her divorcée neighbor.

The show makes clear that there is both a sexual and an affective dimension to the Betty-Glen dynamic. Sexual in the sense that Glen desires Betty and she is aware of it – this is conveyed in episode 4, “New Amsterdam,” in which Glen walks in on Betty while she’s in the bathroom. Staring intently at her semi-hovering toilet squat, he at first refuses to leave, even as she yells at him. To emphasize the physical element, there is a follow-up scene in which Glen tells Betty she’s beautiful and then asks for a lock of her hair. Rather than laughing at or denying the request, she cuts off a piece for him. Compared to the bathroom incident, this offering is potentially more disturbing because it is done with Betty’s consent.

The affective dimension of their intimacy is more apparent in “The Wheel,” the thirteenth and final episode of the first season. Betty encounters Glen in a parking lot, waiting for his mother to return to the car. Through the car window she takes his hand and asks him to comfort her, saying she has no one to talk to. She begins to cry and he becomes uneasy and tells her “I wish I were older.”

In contemporary American media, intimacy is rarely acknowledged as a possibility between adults and children who are unrelated, unless of course, it’s in the context of an exposé of the To Catch a Predator variety. Since children are generally constructed as innocent, adult-child intimacies are almost always represented as exploitative, harmful and, well, predatory. Given the taboo that the adult-child relationship constitutes, how is it that Mad Men is able to portray a relationship between an adult woman and a nine-year-old boy without inciting accusations that it is a sympathetic take on pedophilia? A few potential answers to that question:

For starters, the show adopts a fluid attitude to life phase distinctions. Rather than defining “childhood” as a discrete period that terminates at a specific age, the show often suggests that maturity and majority depend on personal development. Therefore, although Betty is twenty-eight years old, characters in the show, including her therapist and her husband, repeatedly describe her as a “little girl” or a “child.” This emphasis on Betty’s child-like status is also evident in the press and the publicity for the show. A representative example would be the New York Times magazine profile of the series in which Alex Witchel described Betty as an “infantilized” wife and quoted January Jones’ assessment of her character as a “child-like adult.”

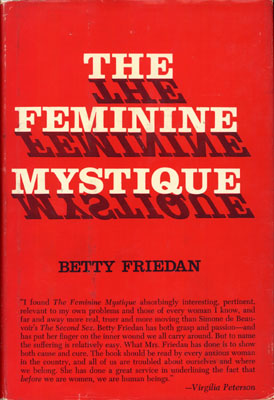

Another pivotal factor is the show’s 1960s period setting. Specifically, the fact that the first season takes place three years before the publication of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique. Already evident in the similarity of names, the influence of Friedan’s work on the construction of the Betty Draper character has been asserted by Weiner in interviews. The description of the housewife as a woman who becomes “infantilized” or “childish” through her dependence on her husband and entrapment in the domestic sphere can be read as an explanation or exoneration for any emotional demands Betty might make on a child. Since she herself is one, how could she know better? Along with the publicity and press references, it is interesting to notice how often references to Friedan come up in online forums devoted to the character. In these comments, Betty is discussed in almost adolescent terms; she’s a girl who will achieve woman status in a few years when she reads Friedan’s book and her consciousness is raised.

Working in concert with the emphasis on Betty’s “childishness” is a characterization of Glen as abnormal or even disturbed. I confess that I don’t personally read him this way, but I have noticed that in summaries of the “New Amsterdam” episode, he is often described as “creepy” or likened to a future serial killer. I think these assessments are based partly on the quietness of his character; because he does not speak much and this is a drama, it is tempting to ascribe all kinds of malevolent thoughts and even soap-opera-esque plot developments to his character. Interestingly, Glen’s quiet solemnity seems in keeping with the representation of boys in at least a few other popular culture texts that include older woman – younger boy encounters (I’m thinking of Birth [2004] and The Ice Storm [1997]). Perhaps the quietness is a way to mark the boys as mature or somehow distinct from the loud exuberance that is assumed to be a part of a normal boyhood. Or the “off-ness” helps to absolve the adult female character of the responsibility for having derailed the boy’s otherwise normal development.

Finally, I’m going to admit that Mad Men does, to a limited degree, offer a diegetic critique of Betty for her relationship with Glen. In “Red in the Face,” the seventh episode of the first season, Helen, Glen’s mother, confronts Betty in a supermarket. She has found the lock of Betty’s hair and demands to know why Betty gave it to him. Expressing her disapproval and disbelief Helen emphasizes Glen’s age, slowly enunciating, “he is nine years old.” By having an adult female character shame Betty for tacitly encouraging a boy’s desire, the show perhaps shields itself from charges that it is promoting any form of child-adult intimacy. Having said that, Helen is far from the most sympathetic character in the show and rather than slinking away in shame, Betty publicly slaps her as a response.

And then, it’s worth noting that Glen has yet to make an appearance in the show’s second season. Not counting myself, I haven’t really noticed anyone mourning his absence. Filling the younger-man void in Betty’s life is Arthur, a riding acquaintance who’s at least twenty. Their scenes smack of Hollywood melodrama, as if both characters are aping the lines and mannerisms of their favorite star performers. Their drama is such well-trodden territory, it’s hard not to read it as parody. But maybe that’s just my bitterness talking. I liked her other boyfriend better.

Image Credits:

1. Glen and Betty: Don’t They Make A Cute Couple?

2. The Beautiful But Lonely Betty Draper

3. Friedan’s Landmark Text

4. Front Page Image

Please feel free to comment.

Thanks, Leigh — great column! I have to admit that I’ve avoided watching Mad Men thus far, as most of the people in my acquaintance who’ve talked about the show are white men who’ve praised it as a text that reminds us, as Americans, how far we’ve progressed in overcoming racism and sexism. As a woman who feels we still have a ways to go in both areas (this current election season but one more reminder), I recoil at this kind of nationalistic self-congradulatory cheer.

But I digress. My point is that I had no idea there was any suggestion of pedophilia in the series. While I haven’t seen the show (as I also don’t have cable), I have followed what the critics have said about it and I find it fascinating that this dimension of the show’s narrative hasn’t come up. I think, as you say, this has everything to do with the perpetrator in question being a woman. If Don Draper was leering at his neighbor’s daughter, I’m sure there’d be much more fodder generated about the show (of course, given that the central character is so complex and flawed, it might take away from the almost universal praise the show has received).

Again, to echo your column, I think this lack of interrogation around pedophilia has everything to do with infantilizing Betty and denying her sexual agency. It speaks to a larger issue about female sexuality — men can be abberant, menacing, or subversive with their sexual proclivities, but women, especially at the time that the show takes place, are saints of the home and enforcers of American morality. I know that a colleague of mine has had to contend with the cultural presumption in her work on girlhood in film that father-daughter or man-girl relationships are presumed as incestuous or pedophilic, but mother-son or woman-boy relationships are not. I think the same presumptions are operating here.

Also, I wonder what this lack of critical inquiry around female pedophilia plays into my suspicions that the show isn’t as progressive as people perceive it to be. Surely Betty’s love interest in season two must be a corrective response from within. Regardless, I will now have to tune in.

Interesting column Leigh. Echoing Alyx, I haven’t seen the series either, although now that it’s being brought up more and more I might have to sit down and watch the first season. What I found particularly interesting in your piece is the construction of Glen and his quietness. Your analysis brings up a lot more questions about how men/boys are constructed and what mannerisms cue the viewer to thinking about the personality of the character.

As the author of one of the episode summaries where he is described as “Creepy” (I believe I also used “Twilight Zone”), and as someone who has actually also taken a stab at writing academically about Mad Men’s first season, I’m delighted to come across this piece.

I think the reason I characterized him using those terms is that there is something about his attention which is simultaneously so blank and yet so caring – he is in love with Betty in a way that she knows (inside) her husband will never be, this kind of pure, unfiltered and unencumbered by work, mistrust or boredom love. I don’t think that this is necessarily just a symptom of her child-like mind (which is sometimes too often used as an excuse for her behaviour), but rather a sign that she knows that she doesn’t have to worry about whether or not Glen means it. At the same time, though, her relationship with Don is still reflected in Glen: she gives him the lock of hair out of habit, almost, as she would feel guilty if someone affections were not reciprocated in some fashion.

Now, couching this relationship in those terms does raise issues of pedophilia, but I think that she is so quick to take on a non-aggressive role in the relationship that this doesn’t become an issue. That scene in The Wheel is where she is beginning to realize that she has no one she can trust, and that all of the lies she’s had to tell herself to trust Don or her therapist have broken down in front of her very eyes. It is no coincidence she comes across Glen, as the producers wanted to give her a chance to re-appraise that scenario. What she says to Glen there is telling: “Adults don’t know anything, Glen.” This is one of our glimpses of the real Betty: not lying to herself about her situation, or pretending to know more than she does, just admitting that age is not a factor in your ability to live, to love.

And in terms of the second season, Glen isn’t necessary anymore: without going into spoilers, Betty has taken on a different role in this game of identities, choosing to essentially try to act out the opposite part. There’s a lot of great work for January Jones this season that can all relate back to the relationship discussed here: that somehow her relationship with Glen was one step in the long term and often bumpy road that is Betty Draper learning how to find her own identity. In Glen there is someone who isn’t even concerned with the question, not even aware of how long twenty minutes is, and thus someone who Betty can envy.

Bah, I’m rambling – this has me thinking too much. Either way, always fantastic to see critical perspectives – will definitely be bookmarking for future reading.

Myles

Cultural Learnings

HI, really liked this column. I have watched Madmen (one of the few shows I have watched recently!) and I was particularly intrigued by this story-line. However – perhaps you know this – a similar relationship was explored in ‘Birth’ with Nicole Kidman where the little boy (Cameron Bright I think) appears claiming to be Kidman’s dead husband. In particular there is a scene where they share a bath together that caused a certain amount of hoo-hah here in the UK – perhaps it wasn’t picked up in the States, it was by a British director Jonathan Glazer.

Another film that has this frisson of course is Tin Drum in which the character (a boy who refuses to grow in stature once he has reached the age of three) is played by a (small) ten year old actor. In one (confusing) scene he is meant to be about 17years old and has a ‘changing room’ scene intimating oral sex with a girl about his age (i.e. 17), later they clearly go on to have some kind of sexual relationship – distinguished by the use of spit and sherbert! From stuff I’ve read about this, there was a US based scandal about the film because the child actor was 10 (playing 17). However when it went to court, the director could prove that there was no ‘exploitation/abuse’ as he still had the out-takes and story boards detailing how various bits of the older actress were ‘covered up’ during shooting!

So yes, I think this kind of relationship is unusual (particularly on TV) but not unheard of.

Karen

This column made me reconsider my reading of Glenn — a character (and a relationship with Betty) that I had previously thought of as poignant, or at least building sympathy for Betty. When she reaches out to Glenn in the parking lot, I don’t read it as desire — on his part or hers — but as despair. Glenn, too, reaches out to Betty in an act of despair, when his mother leaves him to volunteer, his family is in shambles, and we’re clearly led to believe that the other kids think he’s weird and different.

I suppose my need to defend Betty from a word as connotatively ugly as “pedophilia” stems from my sympathy for her in general — especially in the first season — a point that only further reinforces your argument concerning her general nfantilization and the ways in which it excuses or explains her interactions with Glenn.

As the second season unfolds, I’m perplexed and fascinated by her and her exercises of power — as Myles notes, she no longer needs “a Glenn” — and how they diverge from the pendulums of of power on the part of Don, Bobbie Barrett, Peggy, and Pete.

And what do we make of the fact that Glenn is played by the son of Matthew Weiner?

I think, Annie, you raise a very good point: one of the things that sets Betty apart is how isolated she is from everything else, and most of the time not by choice. Most of the power relationships that exist in the series take place in the office, or in the parts of Don’s life outside of her own home. The first season saw a relationship that Betty convinced herself was only between them, when of course she was sharing Don with equal parts his mistresses and his past.

Now, without going into too much spoiler territory, there’s a very subtle shift in the second season where she isn’t quite as naive, and yet she’s more or less like a fish out of water. She doesn’t know what she’s doing, or why she’s doing, but just that she feels obligated to do so. She’s trying to exert power over others, like Don does, and yet all she’s really doing is opening herself up to other people who are looking to play the same role, leaving her vulnerable to people whose innocence is not as pronounced as Glenn’s. One would think her awareness of the power relationships would keep her from falling into these traps, but in reality all it did was motivate her to take more risks and, in the process, endanger herself.

So while she no longer needs a Glenn, this isn’t to say that she doesn’t need someone: if anything right now, she needs to realize that for all of her speeches about how her son is a liar, she’s lying to herself when she tries to be something she isn’t, or more dangerously tries to become like her husband when she has neither the experience or the bravado to pull it off.

As for what we make of the fact that his son is playing the role, there’s precedent that’s largely for practicality – Judd Apatow cast his own kids in Knocked Up, for example, so that they would be easier to get along with (His wife playing their mother would help, no doubt). Considering how difficult it can sometimes be to deal with child actors (or their parents, let’s be honest), casting within the family so to speak gives them some room to work with. Either way, I wasn’t aware of that until I read this article, and I definitely paused for a moment of reflection – I’d certainly say that the casting would eliminate any sense of “pedophilia” being driven by the writing as opposed to our analysis, but that’s perhaps a naive view of the filmmaking process.

Pingback: Mad Men - “The Gold Violin” « Cultural Learnings

I love it! I’ve only seen a few episodes of Mad Men, and haven’t seen any with Glenn — but your breakdown is very insightful, Leigh. Too bad Glenn hasn’t shown up again this season; as I read your recounting of his appearances the first season, and especially the way Glenn isn’t portrayed like your prototypical “boy,” I wonder about a potential queerness of it all. Could part of the reason that Betty and Glenn’s relationship hasn’t necessarily been cast as pedophilic by commentators be the potential that it could be also read as non-sexual, in a queer way? As in, a pre-pubescent gay boy’s fascination with such a paragon of womanhood, ala Marilyn Monroe? Or to put it another way: Will Glenn grow up to be a big ol homo? :)

I very much appreciated Leigh Goldstein’s analysis of the scenes between Glen and Betty, and was also interested in the comments that followed. What Goldstein admirably avoided was overinterpreting what kind of sexuality or sexual expression or even desire was at stake in these few scenes. Some of the comments that follow attribute to the series’ characters rather elaborate psychologies; I think trying to round out a full blown psychology is a rather dangerous strategy in interpreting character development in television series episodes, and across seasons. Writers have various reasons to pick up one thread and discard others in character development, at the same time knowing that fans like to predict and interpret across episodes — which, of course, we are doing here. But I think we should also keep one eye on the way episodes are developed, and what a series reinforces through redundancy and what it leaves as fascinating but rather isolated details about various characters.

For me, the fascination of the Glen-Betty interaction is that it is invested with intense emotional implications that are not spelled out or clearly articulated elsewhere in the script. That is, the impulses of childhood sexuality as experienced by a boy and its impact on an adult, Betty, are sketchily indicated but a clear cut psychology or “meaning” for/behind the two character’s actions is left to viewer interpretation.

I would contrast this with the development of Peggy, whose situation is often narratively developed in highly redundant or overdetermined ways. The script over and over develops incidents that encourage us to interpret various important aspects of Peggy’s “life.” For me, the fascination of the Glen-Betty “sexual” interaction is how little the script adds to the events to allow us to understand more about either of the two’s feelings about their intimate encounter. As a viewer, I can even add that such reticence in the development of this storyline for me has a certain kind of verisimillitude, in that direct encounters between children and adults in sexual situations are both common and fraught with ambivalence, as well as often accompanied by strong feelings. And we have little vocabulary to express what’s going on in these moments. Freud gave us some vocabulary about oral and anal stages that is useful, and the script here references some of that; but I think the script moves the discourse forward and demands of the viewer that s/he try to fill in the story with some sexual/emotional sophistication of her own. Thanks, Leigh, for drawing our attention to a small plotline that has a huge impact.

I couldn’t help but think back to this article after tonight’s second season episode of Mad Men, as it signaled the return of Glen’s character to our narrative. I’d be curious about how Leigh might interpret his second appearance: it captures Betty in a very different place, and her different reaction (And the show’s different reaction) to his actions should be quite telling. At the same time, there’s even greater equation between he and Betty’s situations, each reacting in different ways to the reality of their relationship with parents.

If Betty is “infantilized” then Glenn is adultified. He is basically raising himself,

his mother is either working at her job or spending time on her political volunteer work, and has little time or attention to give him. He is your typical “latchkey child”. He has had to grow up before his time. He also has an absent father. Many young men in this situation, by default, become “the man of the house” and wind up taking on adult responsibilities at a young age. I have personally known a few men who lived this sort of situation back then. They were Glenn’s age back then. In season 4, Glenn is shown working at the Christmas tree lot. He is all of 13-14 at this point. They don’t say if he is taking care of his younger sibling or doing the household chores, but he probably is. I don’t think that this “friendship” had anything to do with pedophilia. It’s what you get when a childlike adult and an adultlike child who are both depressed about their lives and lonely get together. In the last episode, Betty seems to be jealous of Sally’s friendship with Glenn. Now he is showing attention to Sally instead of her, and she can’t handle that. Yes, this woman is sick, make no mistake. She lives or dies based on the attentions (or lack thereof) of males. She has no other self worth. The personality of this character is very well shown. Glenn’s has been left very vague, unfortunately. Too bad the writers didn’t make it more clear.

I was Sally’s age back at the time, and my mother was SO much like Betty Draper, that at times, this show has been painful to watch. I WAS Sally Draper. My mother abused the daylights out of me in numerous ways until I finally got married at age 27. She had post-partum depression and psychosomatic illnesses. She and my father had almost the exact same conversation about psychiatrists (my father,like Don, thought they were quacks) And yes, she did read The Feminine Mystique. I finally got a copy of this book, and came to realize why my mother was so miserable. Unfortunately, back then, I thought it was my fault. And, unfortunately(unlike Don) my father had no problem hitting me when she wanted him to. I have met so many other baby-boomers who lived with these problems as children, that I call my generation “The Wounded Generation”. We inherited all the fallout from “The Greatest Generation” It’s like an epidemic. Very few of us escaped unscathed.

I came across a very interesting article that analyzed a piece of Mad Men’s first season that did not get much attention, yet dealt with a extraordinarily strange issue.

The situation in question is the relationship that Betty Draper has with her neighbor’s young son Glen Bishop who is 9 years old. Personally, when the scenes that revolved around this relationship began to crop up ever so often in the first season, I too thought it to be sort of a non sequitur in the context of what was going on in the show. Though I would not go as far as the author does into the “sexual” nature of the relationship, it was very odd and uncomfortable at some points. One scene in particular actually made me question what the writers were intending with the relationship, which was when Betty actually gave Glen a piece of her hair to keep as some sort of keepsake. I agree with the author when she stated “….this offering is potentially more disturbing because it is done with Betty’s consent.” This scene cemented that Betty was now an enabler in a relationship that began as a seemingly innocent boyish crush, and now turned it into something much more complicated.

I do believe that this plot piece had value for a few reasons more than providing a “…sympathetic take on pedophilia”. Betty’s character is marred with many unflattering traits that mostly stemmed from her upbringing and more so the time period in which the series takes place. With the wave of independence that was occurring in the 1960’s for women, being a homemaker was beginning to become something of an archaic assumption. For Betty who had grown up in wealth, and who now was in a so-called nuclear family, had deep rooted issues with loneliness. With Don being notoriously absent from home life in the first season for work related and sometimes more sinister reasons, Betty was left to fend for herself in the war of home life. With the attention that Glen was giving her it would seem that the void she was carrying was being somewhat filled. He represented someone who admired her beauty and listened to anything she had to say. Both of which her husband Don was not providing. This is where I also agree with Goldstein when she comments on how Matthew Weiner looked to explore the infantilized nature of wives during this period of time. As her own actress described her, Betty was a “child-like adult” and this relationship fully supports that.

What is comes down to is that Betty Draper was very needy and lost at the time and needed someone to fill that gap, no more and no less. Any argument looking into the “pedophiliac” nature of the relationship is unfortunately looking far too deep into subtext.