The Cult of Æon Flux

What happened to the transgressive pleasures of Aeon Flux when it moved from small screen to large?

“You’re skating the edge,” Trevor Goodchild warns his lover, nemesis, and would-be assassin; “I am the edge” Æon Flux retorts in the cult television classic that bears her name. “What you truly want, only I can give,” he insists. Æon’s caustic reply could just as well apply to the transgressive pleasures of cult fandom itself: “Can’t give it, can’t even buy it, and you just don’t get it.” Cult media texts often defy commodification and offer an allure that mainstream audiences ‘just don’t get.’ Indeed, J.P. Telotte argues that a transgressive, oppositional stance in relation to mainstream culture is central to understanding cult texts and their audiences[1]. What is it, then, that makes Æon Flux so fascinating, and why did her move to the big screen polarise her devotees?

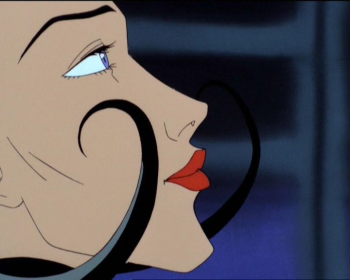

Opening sequence from “Skating the Edge.”

Cult media theorists Sara Gwenllian-Jones and Roberta Pearson refer to cult television as any text “that is considered off-beat or edgy, that draws a niche audience, that has a nostalgic appeal, that is considered emblematic of a particular subculture, or that is considered hip”[2]. Most cult media exhibits several of these characteristics, but Æon Flux, the television series created by animator Peter Chung and later remade as a feature film, incorporates every element. Æon Flux is as definitively edgy as its heroine proclaims. It first aired as animated shorts for Liquid Television in 1991, which developed into a season of half-hour episodes for MTV in 1995. In today’s fast moving mediascape, it is already acquiring ‘nostalgic appeal.’ Through the obvious influence of Asian animation, it also hooks into anime subculture. The show was born from a desire to break the conventions of screen language, and to push creative boundaries with an enigmatic and aggressively anti-narrative style. It seduced its audience, the late night young adult niche market, with an anarchic heroine styled as a leather-clad ‘bitch fatale,’ and it offered viewers more aesthetically and intellectually challenging material than standard MTV fare.

Gaylyn Studlar develops the idea that cult audiences with a taste for excess and perversion express dissatisfaction with the status quo by identifying with transgressive characters who “ritualize perversion into a subcultural icon of rebellion against bourgeoisie norms by celebrating the possibilities of sex as ironic play and playacting”[3]. Studlar argues that the social function of many cult texts is linked to redefining social norms by representing sexual ‘deviance’ and gender performativity[4]. Certainly, Æon captivates her fans with secret messages exchanged via tongues tangled in an illicit kiss, a dominatrix aesthetic, a recurring lesbian subtext, and her role as a Monican spy in a forbidden, passionately adversarial relationship with Trevor, leader of the rival state of Breen. Through identification with Æon, cultists vicariously participate in her transgressions.

Because prime time free-to-air television must cater to ‘family viewing,’ texts that challenge taboos frequently acquire cult status[5]. Æon Flux’s incorporation of a sexualised, violent aesthetic mark it out as forbidden fruit, which augments its appeal in a context where network television is subject to conservative constraints on language, sexuality and violence, by contrast with the more liberal parameters of cinema, subscription television or the Internet. When Æon was expanded to fill a half hour slot, the creative team were under instructions from MTV to reduce the violence in order to avoid Federal Communications Commission restrictions and to make the 30 minute episodes appeal to a broader audience, so they sought subtle ways to ‘maintain the edge’ and push the boundaries, including double entendres in the dialogue, a suggestive soundscape, and oblique sexual references in the imagery.

Æon Flux’s current appeal harnesses the purchasing power of the Y-generation and exploits their access to a wide range of screen technologies. The show continues to draw fans to reruns on MTV, Internet downloads and videos on YouTube, and has been distributed in installments on the screens of mobile phones, thereby conflating its exhibition and reception context with the uptake of mobile and digital technology. In these ways Æon Flux garnered enough of a cult fan base to spawn a feature length live action film in 2005 (directed by Karyn Kusama, starring Charlize Theron), which in turn reinvigorated interest in the original series and generated lucrative DVD sales for both the television series and the film.

While delighted that Æon Flux finally received critical and popular acclaim, many fans of the original series resented the mainstreaming of their passion, and the appropriation of Æon’s identity by a blonde actress and a mass audience. Mainstreaming undercuts some of the primary pleasures of cult fandom associated with identity and identification. When the adored text becomes something that is widely appreciated, the true fan’s identity is no longer experienced as elite or discerning and the knowledge community to which they belong is no longer that of a specialised interest group that defines itself as distinct from the cultural mainstream.

The aura of exclusivity surrounding fans’ relationships with cult texts is evident in the kinds of online material they generate, such as ‘The Purity Test’, which one fan website uses to test knowledge of Æon Flux and implicitly determine whether visitors to the site are ‘pure’ fans or casual drop-ins from mainstream culture. In addition, the expansion of the fictional world of Æon Flux beyond what is shown on screen via multi-platforming is evident in a fan produced graphic novel and comic book miniseries, the Monican Spies online community, and the virtual world of the Æon Flux video game.

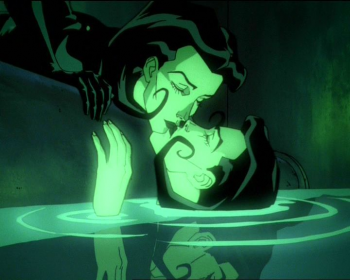

The adaptation from television to film demonstrates that attempts to expand the market for a text often compromise the very qualities that created its unique appeal. As a whole, the film retains superficial elements of the original series, but offers a simplified narrative which blunts Æon’s edge. The television episode most closely related to the film is “A Last Time for Everything,” in which Trevor copies Æon using a process similar to cloning, and she and her duplicate surreptitiously swap places. The original Æon embarks on an affair with Trevor, while the copy completes her mission. The duplication of identity relates to fears about duplicity since Æon is a double agent, but also reflects the desire for a partner and an ally. In the end of the television episode, despite her feelings for Trevor, Æon remains loyal only to herself and works in partnership with her copy, drawing lethal fire from the border guards to enable the second Æon to return safely to Monica. Death is no stranger to the series: Æon dies with the methodical regularity of Kenny in South Park, meeting her demise in each and every one of the original shorts. The certainty of death meant that she was completely unrestrained.

In the television series Æon is an independent agent with her own agenda, exhibiting strong traits of feminism and individualism. These characteristics are taken up in the film in Æon’s defiance of the matriarchal power of the Monican ruler (played in the film by Frances McDormand, although in the television series Monica had no head of state and was therefore ungovernable), and in her quest to derail Trevor’s messiah complex and the patriarchal reproductive fantasies of Bregnan bureaucracy as the regime strives to propagate the human race in the face of infertility. Unlike the television series, however, the film ends by taming Æon, binding her to Trevor in a romantic union that sends them forth into the brave new world beyond the walls of the city, like Adam and Eve in Eden without the original sin. Needless to say, fans of the original series were unimpressed with this ending, which seemed to shackle their deviant, free spirited heroine to the heterosexual, monogamous conventions that she had always usurped. For example, the Æon that fans loved in the original series tartly replied to Trevor’s offer to take care of her in “Chronophasia” with the retort, “Naturally, I’d rather be dead.”

Negative fan responses to cinematic remakes of cult television series are often based on a sense of allegiance and ownership, an investment of fan identity in the original series, or a sense that the remake has not been true to fans’ detailed knowledge of the mythology that surrounds the characters and fictional worlds of cult texts. Indeed, many members of the cult of Æon Flux would far rather see their subversive heroine die than be resurrected in the sugar coated domain of mainstream cinema.

Works Cited

[1] Telotte, J.P. (Ed.) ‘Introduction.’ The Cult Film Experience: Beyond All Reason, University of Texas Press: Austin, 1991.

[2] Gwenllian-Jones, Sara and Roberta E. Pearson. ‘Introduction.’ Cult Television, University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, 2004, p. ix.

[3] Studlar, Gaylyn. ‘Midnight S/Excess: Cult Configurations of ‘Femininity’ and the Perverse.’ The Cult Film Experience, University of Texas Press: Austin, 1991, p. 141.

[4] Studlar, p. 138.

[5] Jancovich, Mark and Nathan Hunt. “The Mainstream, Distinction and Cult TV.” Gwenllian-Jones, Sara and Roberta E. Pearson (Eds.) Cult Television, University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, 2004, p. 35.

Image Credits

1. Frame capture from Æon Flux DVD, episode “Thanatophobia.”

2. Frame capture from Æon Flux DVD, episode “A Last Time for Everything.”

Please Feel Free to Comment.

I wonder, would the film still have failed if it was only screened during late shows, in art theaters, or in decrepit second-run theaters? This, of course, would guarantee the producers little to no return on the cost of making the film, but perhaps such a distribution and exhibition campaign would have forced the show to remain more authentic to its original audience?

I’m superficially aware of fan-generated manga extending from popular manga series. To an outsider like me it seems an anime fan subculture dedicated to producing anime would also exist. Do any readers know of one? If so, has this narrative been touched?

Oh, I do love Aeon. And the big screen character wasn’t nearly as provocative.

I just learned that I’m a fan of cult media. Thanks!

The reason why the film totally, utterly and completely failed to be anything related to the Chung’s series on Liquid Television

is not as complicated as some kind of wish fulfillment of allegiance and ownership. It failed because it did not in any way attempt to

accurately represent the characters of the series but instead created new sitcom actors without any substance. In the anime, Trevor was a cold, super intelligent dictator with benevolent intentions but a flawed delivery of them through his twisted psyche. He is athletic, with intense physical presence. The slob in the movie is nothing like his personality in the anime, in the film he is played as almost insecure, with no stage presence, not in good physical shape, or even nearly at all looking like the character in the series. The least they could do was hire actors that were in shape and perhaps have studied the personality they are acting out instead of being so sloppy.

There are many other things that are a far cry from the series, a lack of subtlety film noir-ish appeal…it isn’t as violent, harsh yet artistic. Sin City is a good example of something that at least TRIED to come close to the real thing. The whole appeal of the series was that it pushed the boundaries instead of drawing inside the box. The film flopped so badly on all of these key identifiers of what the whole creation was. It is like remaking Jurassic Park rated G without the dinosaurs, or remaking the Matrix without any violence. I think Peter Chung said it best:

“I was unhappy when I read the script four years ago; seeing it projected larger than life in a crowded theatre made me feel helpless, humiliated and sad. … They claim to love the original version; yet they do not extend that faith to their audience. No, they will soften it for the public, which isn’t hip enough to appreciate the raw, pure, unadulterated source like they do.” –Peter Chung

Pingback: Æon Flux [Retrospectiva] | Revolución Loser

This article makes sense up until its sixth paragraph, when in the guise of being provocative it just turns asinine. The movie’s problem had nothing to do with Charlize Theron being blonde, or with the cult audience’s desire to remain aloof from mainstream culture — the big problem with the movie is that it had literally nothing to do with the show. I think I and most other true Aeon fans would have absolutely loved to see the show receive a faithful, 2-hour, big-screen adaptation, which would have had to have been animated and created by Peter Chung.

But MTV somehow had just enough balls to allow this show to be made — yet still somehow too few of them to make the film a success. Still, like any true romance, it is better to have loved this show and lost it, than never to have loved at all. Thank you Peter.